Classical Pedagogy and Poetic Tradition: Manner or Message?

Which is more formative for our students: what we teach, or how we teach?

That question has been swirling through classical education circles over the past few years as educators and researchers shift their focus from classical curriculum to classical pedagogy. The conversation may focus on anything from reviving the art of commonplacing, to practicing medieval liturgies of lectio, meditatio, and compositio, to discussing the latest book by James K.A. Smith, to (as Mr. Gibbs has been writing here recently) incorporating monastic habits into a medieval history class. But at the heart of it all is the realization that how we teach might equal or surpass the formative influence of what we teach; or, from another angle, what we teach might actually lie in how we teach.

In reading C.S. Lewis’s Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature to prepare for teaching The Faerie Queene, I came across a passage that, though written about Edmund Spenser’s poetry, seems to speak to pedagogy as well:

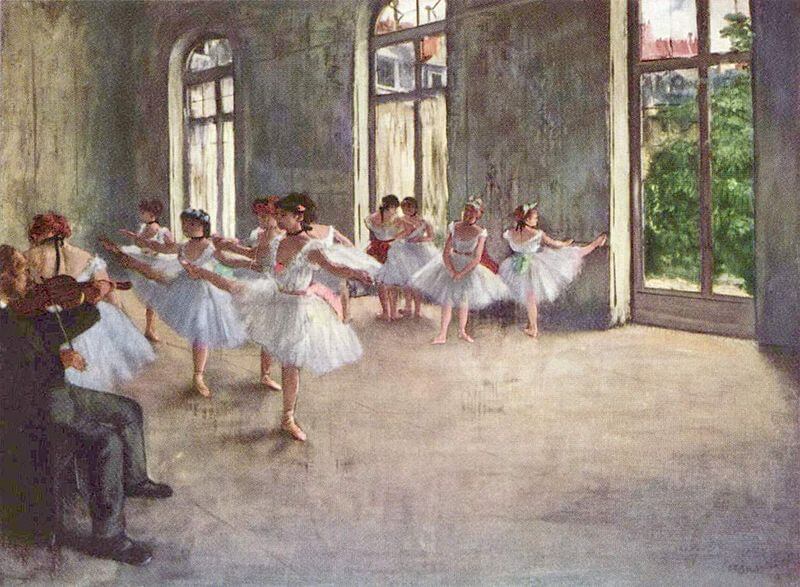

There are moments in literary history at which to achieve a manner and a music is more important than to deliver any ‘message,’ however profound or prophetic. The message can wait; it will have to wait forever unless the manner and music are found. It is idle to talk about a great ballet until people have, in the crudest and simplest sense, learned to dance, learned the steps.

In context, Lewis has been describing the literary context in which Spenser wrote—a stifling, formulaic period between the glorious improvisation of the Middle Ages and the fresh themes of the English Renaissance. Lewis claims that Spenser’s early poetry, particularly The Shepheards Calendar, does not achieve depth of meaning; however, it breaks out of the stale poetic patterns to inaugurate forms and figures that will someday bear the weight and beauty of his mature work, as well as that of his successors.

If teaching, like poetry, is an art, then could this statement not apply to it too? There are moments in the history of education at which to achieve a particular manner and music—a desire to learn for wisdom and virtue rather than grades and jobs, a demeanor of wonder and humility towards tradition, a posture of contemplation rather than “covering material”—is more important than to deliver any message . . . even a message that sets the teacher’s heart a-quivering, like the extraordinary subversion of the epic tradition to Christianity in Paradise Lost or the stunning mathematical elegance of Brunelleschi’s dome.

Admittedly, to some extent, this is a false dichotomy: teaching always has both a “what” and a “how,” a pedagogy and a curriculum. True, beautiful, good messages have a way of inspiring and supporting true, beautiful, good manners.

And yet, the assumption that “manners precede message” could be a profoundly wise guide through the myriad instantaneous choices that the teacher must make, whether standing in a classroom or sitting at a schoolroom table. The tone of voice in response to a sincere but off-topic question, for instance, can either stifle or ignite curiosity: do we sound exasperated or intrigued? Modeling a gratitude for the great books and great ideas might be more important than exhaustively explaining the great books and great ideas: do we catch ourselves before apologizing for what we are teaching? The way that we approach grading and assessment will shape students’ souls far more than the grades themselves: do we anxiously focus on numbers, or do we patiently emphasize learning through feedback?

The daily, repeated practices that eat up class time may prove more influential than the profoundest lectures: what of morning prayers, commonplacing, singing the doxology?

This manner and music, no less than the books and ideas of its message, forms the classical tradition. And if we hope to rejoice with our students in the great dance that it is, we must patiently teach them the steps.

Lindsey Brigham Knott

Lindsey Knott relishes the chance to learn literature, composition, rhetoric, and logic alongside her students at a classical school in her North Florida hometown. She and her husband Alex keep a home filled with books, instruments, and good company.