Why Children Need the Liberal Arts

No one understood what we were doing in our homeschool. Trying to explain classical education would bring the common response, “So, you read books and go outside?” People just couldn’t understand what classical education was or how it prepared our children for the future in today’s society—which is why, when our first child began his last year of high school, they questioned what he would be able to do once he graduated.

“I’m guessing you’re just going to get a job?”

“You’ll attend the community college, won’t you?”

“Are you looking into learning a trade?”

People inundated with public education couldn’t quite grasp the depth and intensity of a classical education.

I found myself getting defensive.

“Our son has been reading, writing about, and discussing college-level books since he was twelve! He can have conversations about and share his opinions on historical events, philosophy, and scientific theory. He’ll even talk to you about Jane Austen! He’s prepared for college, a career, a trade, or anything else he wants to do.”

I’d have long conversations trying to explain education in our home and be met with blank stares. I would tell someone our son was reading Faust and having grand discussions with us about the ideas enmeshed within it; they would ask if he knew algebra. I explained that our son would rewrite Emerson’s essays in his own words, and they would ask if he knew how to write a research paper with proper documentation. I told them that he could recite “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” and they would squint their eyes in confusion and ask if he knew how to use a computer.

I realized then that it didn’t matter to people how remarkable my children’s education was; if it didn’t fit into their neatly constructed box of what education was supposed to look like, it didn’t count.

I began to sum up our educational life with a beautiful and inspiring quote from educator Charlotte Mason: “The question is not—how much does the youth know—when he has finished his education, but how much does he care.” I was told how nice it sounded but that it would not prepare our children for getting into college or living adult lives.

Finally, the day came when our eldest was accepted into his first-choice college, and I naively assumed that the questions and confusion would stop. We had done it! We had homeschooled a child through middle school and high school, and now he was headed off to college. I thought that people would start to see the wisdom behind what we were doing with our children.

But this time, instead of dismay and confusion over homeschooling and classical education, I was bombarded with laughter and eye-rolling.

“He’s going to a great books liberal arts college?! What even is that? Hahaha!”

“We call that the most useless degree on the planet! Good luck!”

I’m not exaggerating; people actually said these things. And while there were more positive comments than negative ones, the negative ones really stuck out.

While many homeschooling families promote a liberal arts education, a society that values test scores above everything else fails to understand the importance of it, questioning the intelligence of classically homeschooled kids and writing them off as “those weird kids who read old books and learn dead languages.”

After reading Back to Freedom and Dignity by Francis Schaeffer, I was able to fully grasp the importance and place of the liberal arts in our world. This work illustrates the idea that having the ability to do something doesn’t mean you should. It shows that the path to freedom, true choice, and breaking out of society’s mold comes by doing what is right, not what is possible.

Schaeffer writes, “Here are men who are doing the manipulating and are fearful of what they are doing. Like the scientists who made the hydrogen bomb, the men who really understand are troubled. Why do they do it then? Because they live in a universe with only one boundary condition. Christians have two boundary conditions. The first one is what they CAN do. And the second is what they SHOULD do. Modern man does not have the latter boundary. Only technology limits him. Modern man does what he CAN do.”

Using this concept, I was able to explain to people why we educated our children using the classical method as well as why we fully supported, and even encouraged, our son to attend a liberal arts college and receive his bachelor’s degree in a supposedly “useless” field. Skills, trades, facts, and tools can easily be picked up, but kindness, goodness, and righteousness require something altogether different, something that touches the heart and soul of humanity.

This world needs people who have had a classical education. It needs people who study the liberal arts as children and in college. It needs people who have learned to carefully consider whether something is good, noble, and right before they make decisions instead of just doing something because they can. This type of education grows people. It helps build a heart of compassion and courage in them.

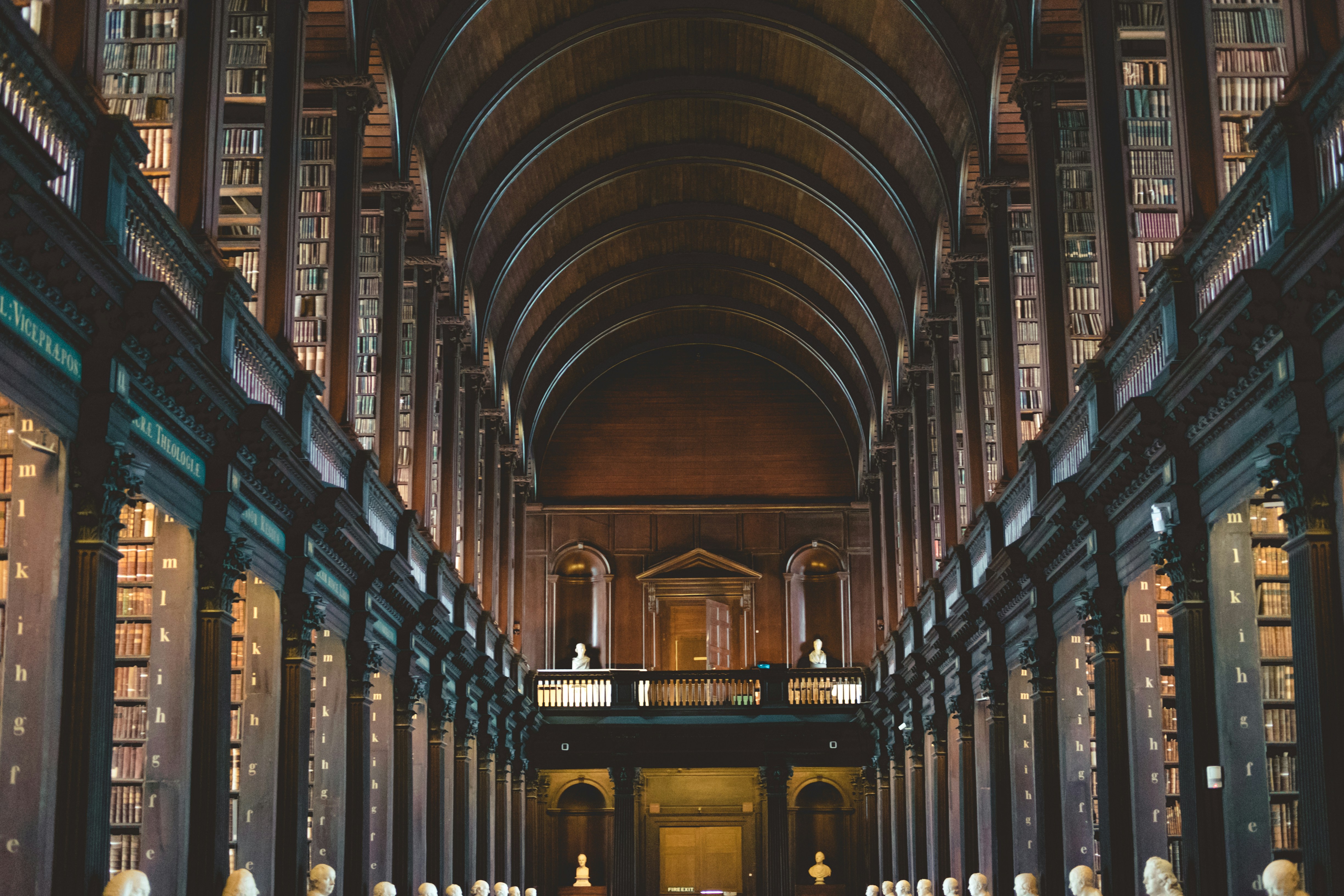

The people we want to become our doctors, our scientists, our teachers, and our politicians are those who were raised on a steady diet of great books, who can feel the depth of emotion and passion in a painting or symphony and delve into the meaning of a poem. The people we want leading and making hard choices are the people who remember Horatius at the bridge, standing firm and courageous to save his men and his city. They are the ones who have read Benjamin Franklin’s own words, who have witnessed the waltz between Jean Valjean and Javert, who have contemplated the loyalty of men following their captain to destruction. These are the ones who can face hard decisions, dig deep into their souls, find an example of the good and the true to follow, and when all is against them, choose what is right.

As classical parents, we are often asked, “Why are you doing this? What’s the point?” We need only think of the brokenness of the world around us and then open up a Dickens novel, gaze upon a Rembrandt painting, listen to Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, or lie under the stars at night to answer.

Everything. Everything is the point.

Amy Hughes

Amy Hughes is a homeschooling mom of 9. She is author of the book Words Like Honey: How to Avoid Unintentional Harm, Model Kindness, and Nurture Your Child’s Faith Through What You Say. Amy is a speaker and writer who lives on the central coast of California.