Zeitgeist: A Play In One Act

Zeitgeist was originally published in Blasphemers.

SCENE ONE

(A sparsely set stage. On stage left, a dresser. In the middle of the stage, a bed. A suitcase on the bed. PHILLIP moves back and forth between the dresser and the suitcase, packing his clothes. MARTHA enters the room from stage right.)

MARTHA: (calmly, soberly) Where will you go?

PHILLIP: East. To the mountains.

(MARTHA watches as PHILLIP goes back and forth, hastily packing his suitcase.)

MARTHA (continued): What do you think you’re going to find there?

PHILLIP: I want to find myself. I can’t marry you until I know who I am.

MARTHA: You want to find yourself?

PHILLIP: Yes.

MARTHA: Who’s going to do the finding?

PHILLIP: I am.

MARTHA: (frustrated) Well, that’s who I want to marry. I want to marry the “I am.” I don’t want to marry whoever you find out there. I want to marry the man who’s going out looking, and we both know who that is. It’s you. Right here, right now.

PHILLIP: You know what it means when a man says, “I want to find myself.” Don’t play games.

MARTHA: Suppose you find yourself, and yourself is a fool. Then what? Are you stuck being a fool for the rest of your life just because that’s who you are?

PHILLIP: I’m not going to find a fool. I might stay a fool if I don’t go out looking, though.

MARTHA: If you’re going out looking for yourself, who have I been talking to, and praying for, and loving up until now? Who was that?

PHILLIP: I don’t know, but my old name isn’t good enough anymore. It was never up to the task. I need a new name.

SCENE TWO

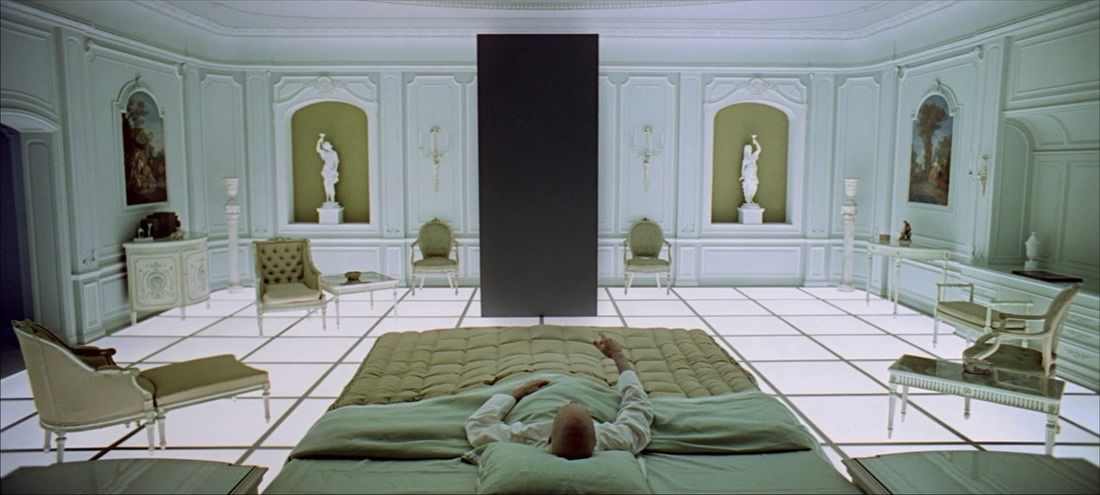

(EDMUND lays on the forest floor, sleeping. Behind him is a large black monolith, of the exact same dimensions as the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. PHILLIP is trekking through the mountains, enjoying the scenery, when he comes across EDMUND.)

PHILLIP: Are you asleep?

EDMUND: Wide awake.

PHILLIP: (pointing at monolith) What in God’s name is that?

(EDMUND does not reply)

PHILLIP: It looks like that thing from… that one movie.

EDMUND: Never saw it.

PHILLIP: Sure you did. Everyone saw it. The movie with the monkeys. The spaceship.

EDMUND: I never saw it.

PHILLIP: You been here long?

EDMUND: Yes.

PHILLIP: How long’s that thing been here?

EDMUND: Longer than me.

PHILLIP: Has anyone else seen it?

EDMUND: Everyone who comes this way. You’re the twelfth person today.

PHILLIP: What do other people say when they see it?

EDMUND: They stop and look. Then they ask questions. Then they want to touch it, and when I tell them they can’t, they start complaining that it’s ugly and that someone should paint it.

PHILLIP: Is it yours? Why do you get to tell people they can’t touch it?

EDMUND: I’m just the custodian.

PHILLIP: Do you touch it?

EDMUND: I’m allowed to.

PHILLIP: Who gave you permission?

EDMUND: The last custodian.

PHILLIP: How many custodians have there been?

EDMUND: Two hundred and eighty-six. I am the two hundred and eighty-seventh.

PHILLIP: (stunned, then incredulous) Well, I guess I’ll leave you to it, then.

(PHILLIP begins to move on, but stops and turns to look at the monolith again)

PHILLIP (continued): What would you do if I tried to touch it?

EDMUND: I would prevent you from touching it.

PHILLIP: Why? What do you care?

EDMUND: What do you care that I care? Never fails to impress me. People without a care in the world pass by this very spot every day, and as soon as they hear they cannot touch the Tree, they become suspicious, then angry. Some even turn violent.

PHILLIP: You call it “the Tree”?

EDMUND: Yes.

PHILLIP: It doesn’t look like a tree. It looks cold and dead.

EDMUND: Everyone says that. But after you spend a little time with it, study it, gaze at it, eventually it starts to look different. It starts to look alive. Only I can see it for what it really is.

(PHILLIP is incredulous)

PHILLIP: You’re crazy.

EDMUND: That’s fine.

PHILLIP: And a fool.

EDMUND: I never asked for your approval. I’m just a man in the mountains.

(PHILLIP considers this for a moment and settles down a little.)

PHILLIP: How long have you been in the mountains?

EDMUND: Four years.

PHILLIP: Are you going to spend the rest of your life up here?

EDMUND: No. Someone always comes. At least, that’s what I’ve been told.

PHILLIP: Who comes?

EDMUND: Someone will come to take my place.

PHILLIP: Who?

EDMUND: Someone. Maybe you.

(PHILLIP reacts to this with amusement, but he says nothing. After a beat, he changes the subject)

PHILLIP: When was the last time you had a drink?

EDMUND: Four years ago.

PHILLIP: You married?

EDMUND: I am.

PHILLIP: I bet she doesn’t visit you up here.

EDMUND: That is true.

PHILLIP: When was the last time you saw a film?

EDMUND: Four years ago.

PHILLIP: What do you eat?

EDMUND: People bring me things.

PHILLIP: None of this makes any sense. What do you mean someone will take your place? What do you mean I might take your place? Take your place doing what?

EDMUND: Guarding the Tree. But if you want to guard the Tree, there is a vetting process.

PHILLIP: (laughing) Really? Is it difficult?

EDMUND: No, but it’s time consuming. If you want to become the custodian of the Tree, you have to stay here for a year, and the two of us will guard the Tree together. If you stay here for an entire year, then I will turn the Tree over to you. Then I can go home, go back to my wife. Then you stay here alone and wait until someone will wait and watch with you for a year. Then you can go back to your life. I should warn you, though, that most people give up.

PHILLIP: How many have given up?

EDMUND: That’s not the question. The question is how long they have lasted.

PHILLIP: How long have they lasted?

EDMUND: One man lasted a month. One lasted a week. One lasted a day. One lasted just a few hours.

PHILLIP: Why did he give up so quickly?

EDMUND: He got hungry. He ran out of trail mix and got hungry.

PHILLIP: What about the guy who lasted a month? Why’d he quit?

EDMUND: He missed his wife.

PHILLIP: And the guy who lasted a week?

EDMUND: That guy started to worry about his kids.

PHILLIP: And the guy who lasted a day?

EDMUND: He got bored. His cell phone died. He actually came back a few weeks later. He was also the guy who only lasted a few hours.

PHILLIP: I wouldn’t last long. I have a fiancé waiting for me.

EDMUND: Then what are you doing here?

PHILLIP: I told her I needed to figure out who I was. She was not pleased.

EDMUND: You should definitely go back and marry that one.

(PHILLIP is thoughtful for a moment, then becomes a little agitated once again)

PHILLIP: So what happens if there’s no one here to guard the Tree? Who cares? What use is the Tree? What’s it good for?

EDMUND: The Tree doesn’t change. Everything else changes, but not the Tree. The Tree stays the same so that everything else in the world can move, or progress. If nothing stayed the same, there would be no way to measure progress. The whole world would just be chaos, tumult. But if one thing stays the same, then everything else can be measured. Everything in the world is either nearer or farther from the Tree.

PHILLIP: If the Tree doesn’t change, why does it need a guardian?

EDMUND: It doesn’t need me. I need it.

PHILLIP: If you need it, then maybe I need it, too. Maybe everyone does.

EDMUND: That’s true.

PHILLIP: Then why put the damned thing up in the mountains where no one can get to it?

EDMUND: You got to it just fine.

PHILLIP: By luck!

EDMUND: Whether it was lucky or not that you found the Tree is yet to be seen. You’ve only been here for a few minutes and I have a strong suspicion that in a few minutes longer, you will simply keep going on your way.

PHILLIP: That’s the appeal of the thing. That’s why you’re here. It’s snobby. It’s elitist. You put it in the mountains where no one can get to it—

EDMUND: You got to it.

PHILLIP: —and you play to a man’s ego. You make a man feel like he’s really special in leaving the world behind to guard it.

EDMUND: What do you think would happen if the Tree were set down in the middle of the public square?

PHILLIP: It might do someone a little good.

EDMUND: Why would anyone down there love it?

PHILLIP: For the same reason you love it.

EDMUND: You don’t know why I love it. You have not even asked.

PHILLIP: The only reason you love it is because other people can’t. You’re a snob.

EDMUND: Anyone could take my place, though.

PHILLIP: After a pointless wait! And only if they are willing to leave their entire lives behind!

EDMUND: If the Tree were in a public square, countless people would begin the year long wait and no one would finish it. There would be too many distractions, too many temptations.

PHILLIP: How can life itself be a distraction? That’s elitist. Admit it.

(EDMUND sits down, puts an unlit cigarette in his mouth)

EDMUND: Many people have passed by here and many have stopped to talk. As soon as people understand what the Tree is, they propose changes. They have some bright ideas. Then they become offended when their ideas are not immediately accepted. Then they begin with the accusations. I’ve been kicked and slapped more times than I can count. People spit on me. They annoy me. Once, a woman sang a stupid, vulgar little song for nine hours to try to get me to move. Some people say they’re being cruel to be kind, that they’re trying to wake me from a trance. If you want to take the Tree down to the public square, wait with me for a year. You can take over. I’ll go back to my life, and you can do whatever you want to with the Tree.

PHILLIP: Really?

EDMUND: No. But even if it was true, you wouldn’t do it.

PHILLIP: Why can’t you move it?

EDMUND: Because I don’t want to. I don’t have the will to move it.

PHILLIP: What if you did?

EDMUND: Around six hundred years ago, a certain obstinate young man told the old guardian he was going to wait for a year, become the new guardian, then destroy the Tree. Every morning, he woke up and taunted the old guardian by saying, “When it is my turn, I will put an end to this stupidity. When the Tree is mine, I will destroy it.” He said the same thing every night for an entire year—

PHILLIP: Let me guess. The day he became guardian, something mysterious happened to him and he no longer wanted to destroy the Tree.

EDMUND: If you consider suddenly dying of dysentery to be mysterious. And it was the day before he was to become guardian, not the day of.

PHILLIP: What a lot of pious nonsense. Look, I hate to break it to you, but—

PHILLIP and EDMUND: (simultaneously) –that thing cannot be the actual Tree.

EDMUND: Yes, I know. Trees don’t grow from nothing. They grow from the ground, which means that the ground was here before the Tree. Don’t be too proud of yourself, though. That is usually the first objection people lodge when they hear the Tree does not change. If the Tree is really without change, how did it grow out of the ground? How can anything which gives life not change? Does not giving and growing imply change? Very clever.

PHILLIP: You can’t simply restate honest questions in a sarcastic tone of voice and pretend you’ve given rational discourse its due.

EDMUND: What do you propose I do?

PHILLIP: Would you care to revise the claim that the Tree never changes?

EDMUND: This is an icon of the Tree, although I wouldn’t count that as a revision of what I said.

PHILLIP: It sounds like a revision.

EDMUND: If I handed you a picture of Stanley Kubrick, I could say, “This is Stanley Kubrick,” or I could say, “This is a photo of Stanley Kubrick.” Either statement would be fair. So this is the Tree. It is an icon of the Tree.

(PHILLIP rubs his jaw and looks thoughtful for a moment. The name Stanley Kubrick sounds familiar and he is trying to place the name. After a moment, though, he gives up trying to place the name.)

PHILLIP: So where’s the real Tree?

EDMUND: A photo is not a fake.

PHILLIP: (frustrated) Where’s the thing depicted in the Tree?

EDMUND: (shakes his head) Everywhere. Nowhere. I don’t have a great answer for that question.

PHILLIP: You don’t have a great answer for most of my questions.

EDMUND: Your questions don’t have a great tone.

PHILLIP: So if this isn’t even the real Tree, why do you care about it?

EDMUND: I care about it the way an imprisoned man cares for a picture of his sweetheart.

PHILLIP: (gestures at the Tree) But if this thing changes, the real Tree wouldn’t change. The real Tree is nowhere, so how could it change?

EDMUND: I don’t accept your terms. We can speak of “the lower Tree” and “the higher Tree,” but not in terms of “real” and “fake.” If you insult the Tree again by suggesting it is fake, this conversation will be over.

PHILLIP: How profoundly childish. I’ll call it whatever the hell I want to call it.

EDMUND: Well, you may call it what you like, and this conversation may end.

PHILLIP: You’re not obligated to spread the good news of the Tree to whoever asks about it?

EDMUND: I’m obligated to stay here until someone worthy takes my place.

PHILLIP: Fine. If the lower Tree changes, the higher Tree doesn’t. The lower Tree is just a thing, an object, like countless other objects. What does it matter if it changes?

EDMUND: You would like to see the Tree change, wouldn’t you? You would like to try to push it over, just to see if it would fall.

PHILLIP: Yes.

EDMUND: And if it fell, then you could go back to your business of finding yourself.

PHILLIP: Yes.

EDMUND: The only reason you’re here is because you’ve encountered an awful lot of things before which claimed to be the Tree, in a manner of speaking. You’ve pushed those things over and then kept moving on, disenchanted. I get it. It’s only natural.

PHILLIP: (calmly) In a manner of speaking, yes.

EDMUND: That’s because in all the things of the world and all the people in it, there are really only two powers, only two ways of carrying on. There is the Tree and there is the Zeitgeist. At the moment, you’re the Zeitgeist. Or an icon of it, at any rate.

PHILLIP: You’ve got a little ghost story to explain pretty much everything, don’t you? What exactly is the Zeitgeist?

EDMUND: The Zeitgeist is a beautiful young woman who whispers in your ear and tells you to make things better.

PHILLIP: And what’s wrong with that?

EDMUND: We’ve been talking for awhile now. What do you think I’m going to say?

PHILLIP: That things can’t actually get better. That the less things change, the better they are, and that changing the way things are always makes them worse.

EDMUND: Very good.

PHILLIP: What about changing things so that they’re more like the way they were?

EDMUND: That’s unchanging them.

PHILLIP: What’s so great about the way things were?

EDMUND: The way things were is always closer to the power which brought things into existence in the first place, and the power which brought things into existence is also the power which sustains the way things are. The Zeitgeist is the spirit which moves things away from the power which brought things into existence.

PHILLIP: But the Zeitgeist had to come from somewhere. It must have come from the Tree.

EDMUND: Clever. Yes and no. The Zeitgeist hasn’t always been the Zeitgeist.

PHILLIP: And before it was the Zeitgeist?

EDMUND: The Zeitgeist was an apple which fell from the Tree and rotted.

PHILLIP: Why did it fall?

EDMUND: There is no reason.

PHILLIP: You don’t know, do you?

EDMUND: There is nothing to know. The Zeitgeist is opposed to reason. I don’t mean the Zeitgeist is a thing which opposes reason. I mean the Zeitgeist is the opposition to reason itself. It has no cause. It doesn’t come from anywhere. It’s not a thing, but a nothing.

PHILLIP: Why would anyone follow nothing?

EDMUND: Because nothingness does a very convincing imitation of everythingness. Nothing is just fake everything, and the Zeitgeist is a fake Tree. The Zeitgeist offers a painless path to the Tree, a path where there is no year long wait, and the Tree can be broken to pieces, refashioned in impious shapes, and painted every color of the rainbow.

PHILLIP: But why would anyone want to do such a thing if they were not already following the Zeitgeist?

EDMUND: I don’t know. Even the Tree doesn’t know.

PHILLIP: There’s no little ghost story which explains that one away, is there? You don’t have all the answers after all.

EDMUND: Do I seem embarrassed of that fact?

PHILLIP: You ought to be. What’s wrong with moving away from the Tree?

EDMUND: Everything dies apart from the Tree. Nothing lasts.

PHILLIP: You’re going to die.

EDMUND: And if you find yourself, you will die, as well. If you don’t find yourself, you will simply be nothing. You won’t die because there won’t be any you to die.

PHILLIP: If I die before I find myself, at least I will die on my own terms.

EDMUND: Whose terms?

PHILLIP: Mine.

EDMUND: And who is that? If you don’t know who are, how will you know when you’ve “found yourself”? Yourself doesn’t exist.

PHILLIP: Who are you?

EDMUND: I am the Tree.

PHILLIP: But you’re going to die.

EDMUND: When I die, the only thing that dies is the Zeitgeist.

(PHILLIP pulls a knife from his back pocket)

PHILLIP: Is the Tree going to save you?

EDMUND: It already has.

PHILLIP: You said the Tree doesn’t change, and so the Tree is the only way we can measure progress. That means there’s something beyond the Tree. Something good.

EDMUND: The Tree doesn’t change, but that means it measures decline, too. So far, there hasn’t been any progress. The Tree is the first thing. But because it doesn’t change, it’s the last thing, too. When people measure how far they’ve progressed from the Tree, they’ve really just measured how far below the Tree they’ve fallen. But I see you’ve got a little instrument of progress in your hand there.

PHILLIP: Don’t be glib.

EDMUND: I think you found yourself.

PHILLIP: I’m going to push it over. Then I’m going to drag it down the mountain and let people tear it up.

(EDMUND nods, thinks a moment)

EDMUND: (pointing with his thumb) There’s a little grassy spot over there which overlooks the valley. That’s where they usually take us. The digging is already done and there’s a sturdy shovel there you can use to fill in the dirt, if you like.

PHILLIP: That’s where who usually takes you?

EDMUND: Don’t be glib.

PHILLIP: Who else is over there?

EDMUND: The other custodians.

PHILLIP: But you’re the 287th in a glorious, unbroken succession. It all ends with you now. You’ve lost. The others lost, too. Why so resigned?

(EDMUND turns and walks off stage right, in the direction he gestured to only a moment earlier. PHILLIP follows but pauses in front of the monolith. He looks up at it, sighs, the exits the stage. A very long moment passes. Then EDMUND walks back on stage. He is now dressed in a white shirt which is stained with blood. We are uncertain whether he is a martyr, or whether he has killed PHILLIP. He stands with his back to the audience and looks up at the monolith. Then he sits down while continuing to gaze up.)

THE END

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.