You Are The Curriculum

“You are the curriculum.” Last week, my esteemed colleague Andrew Smith offered this proverb while addressing the secondary faculty of Veritas School on the subject of rhetoric. As I plan my first week of classes, the proverb has taken seat in my heart. Christ claims that “Everyone who is fully trained will be like his teacher.” Christ does not claim that everyone who is fully trained will be “like the authors of the books his teacher passed out.”

In similar fashion, Grant Horner taught me to not hand out a syllabus for the first week of class, and neither to cover any rules on the first day of class. The teacher must cover the rules, but first things and final things posses a great inherent weight which middle things lack, and if the teacher begins the year with rules, his students understand that nothing is more important than rules. Instead, the teacher should begin the school year with a tornado, an earthquake, a fire, and a still small voice.

Do not begin the year by covering the books in the curriculum. Get around to the curriculum in the second week. That’ll show ‘em. Granted, you have more to cover than is humanly possible, and you have meticulous plans for how you will finish 2600 pages of literature before May 30th. Still, do not begin the year by covering curriculum. You do not teach curriculum, you teach virtue and wisdom. Covering curriculum is an accident of teaching virtue; teaching virtue is not an accident of covering curriculum. Reading great works of literature is one of the finest ways of teaching virtue, though plenty of men and women have achieved sainthood without good classical educations. No one has achieved sainthood without virtue, though, even if that virtue was only realized in the closing moments of life.

If you begin the school year by reading old books, your students will believe the point of the class is reading old books. Reading old books is a perfectly arbitrary thing to do, though adults ask children to do scores of arbitrary things, and so throwing one more on the heap is not particularly offensive. Begin the year by reading old books and your class will, for the next nine months, at best, merely be inoffensive. If the old books are going to be of value to the students, though, they need to know what the point of reading them is. He who has a why to read old books can bear almost any how, as Friedrich Nietzsche might have said.

Begin the year by asking all the students to make a list of ways they can become better Christians. Ask them to come up with ten things they could do, and make a list yourself. Certain righteous works will likely appear on almost everyone’s list: read the Bible more, pray more, spend less time on the internet, help mother around the house, confess secret sins, give to the poor, and so forth. After everyone has made the list, ask a few to share what they have written. Spend a few minutes discussing these good works, and then, after a good pregnant pause, say, “Alright, now everyone go home and do what you wrote down.” Everyone will laugh and say, “Yes, yes, ha ha! That’s the trick, isn’t it?” And after the laughter has died down, say, “Honestly, what is keeping you from doing these good things?” Praying more often is not like brain surgery. Twelve years of education will keep me from performing brain surgery tonight, though only my laziness will keep me from reading my Bible tonight. I do not read my Bible because I am wicked and do not like the Bible very much. What keeps us from doing most good things is simply lack of desire. Tell the students, “I do not do good things because I do not want to do them. I am not even sure I want to want to do good things. I would wager I want to want to want to want to do good things. Perhaps you are in the same boat. By the end of the year, I would like to lay bare one of those “want to’s” and make it easier for you to want to do good someday. You will probably not want to do good by the end of the year, but that is okay. Baby steps to the front door.”

And that’s the whole first day of class.

Similar kind of thought experiments can be performed Tuesday, Wednesday, and so forth, and after the students are completely confused about what the devil kind of a literature class this even is, anyway, tell them, “Today we’re going to read Boethius, but we’re only reading Beothius to lay bare our desire for God. Reading Boethius is a way of helping us understand where we are weak and selfish.”

Your students will not learn Boethius so much as they will learn to imitate your love of Boethius.

They will not submit to Boethius, but they will submit to your submission to Boethius.

They will not learn Boethius, but they will learn what is worthy of love.

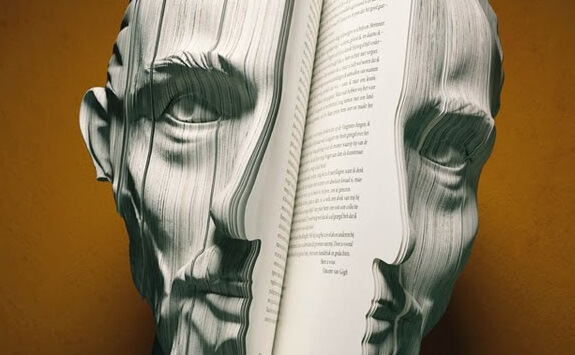

Your students will not learn the books you teach, but they will learn the one who teaches the books.

You are the curriculum.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs is the director of The Classical Teaching Institute at The Ambrose School. He is the author of Something They Will Not Forget and Love What Lasts. He is the creator of Proverbial and the host of In the Trenches, a podcast for teachers. In addition to lecturing and consulting, he also teaches classic literature through GibbsClassical.com.