The Work of Writing History, A Review

Fiction, memoir, biography, history, essay-collections, reportage, science, philosophy, theology, writing that takes off from movies and music and art and more: which branch is most inadequately assessed in our public book-talk, in reviews and podcasts, on Twitter and elsewhere? I would say history, hands down. But what do you get when you read a typical review of a work of history? Mostly a summary of the subject at hand. Insofar as there is any account of the writing, it is likely to be limited to a few stock responses, pro or con (the historian is “biased,” leaning too obviously “left” or “right”; the historian is dumbing his subject down or writing only for fellow-mandarins, but—let there be trumpets and zithers—now and then she is wonderfully “readable,” etc., etc.). What we rarely get is any acknowledgment that writing history requires imagination every bit as much as it requires research. It is not an assemblage of “facts.”

This came to mind as I was reading an advance copy of Barry Strauss’ splendid new book The War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium, coming in March from Simon & Schuster. Strauss is one of my favorite historians, and this may be his best book in a distinguished career. Those who have a particular passion for the classical world (or simply a fascination with Antony and Cleopatra), not to mention connoisseurs of great naval battles, should already have this book on their wish list, but Strauss is writing for a broad audience.

Consider this brief passage from Strauss’s prologue, in which (at the very outset of his book) he describes the once-famous monument created by the victorious Octavian (soon to become Augustus Caesar) around 29 BC, two years after the Battle of Actium—a monument that until recently had long been obscured. “At Nicopolis,” Strauss observes, Octavian wrote the history of his triumph “in stone.” But then, Strauss adds, “he also wrote it in ink, in Memoirs that were famous in antiquity” but that vanished “long ago”; only fugitive fragments survived.

This is an incidental detail, and yet it will give the attentive reader a jolt. How did that happen? The Memoirs of the great Augustus Caesar were simply lost? In conjunction with the more developed account of the monument at Nicopolis, obscured for centuries, this nudges us to step back from our own moment, to recognize that much we take for granted will also be erased in the vicissitudes of time.

Strauss’ book is loaded with moments like this, along with his persuasive argument for the historical consequences of Octavian’s victory (“If Antony and Cleopatra had won, the center of gravity of the Roman Empire would have shifted eastward”), the immersive details of battle between the contending forces (including a crucial contest some months before the massive sea-battle at Actium), intense personal passions, and intricate behind-the-scenes maneuvering on both sides, including a good deal of old-fashioned espionage.

To keep all these lines of the narrative in play, now foregrounding one, now highlighting another, holding the reader’s attention with no sense of disorientation, requires skills akin to but not identical with those of a gifted novelist. This crucial aspect of history-writing—whether it be superbly managed, as here, or shoddily handled, as is sometimes the case—routinely gets short shrift in reviews. Be sure to savor the art and the craft as you read.

The official pub date for The War That Made the Roman Empire is March 15. That same day is the pub date for Peter Handke’s Quiet Places (FSG), a collection of essays, two of which have not previously appeared in English. (Also on March 15, FSG will publish a translation of Handke’s novel The Fruit Thief, which appeared in German in 2017.) Even if you haven’t read Handke, you may remember the controversy (if that’s the right word) in October 2019 following the announcement that he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Handke, critics charged, was an apologist for genocide perpetrated by Serbs against Bosnian Muslims. One writer, the former editor of the books section of a major U.S. newspaper, bragged that she had never read Handke and didn’t intend to start doing so now.

In response, I wrote a column for First Things in Handke’s defense called “Why You Should Read Peter Handke.” At that point, I expected that most of the leading bookish magazines and journals would be assigning retrospective accounts of his long career in the wake of the prize and the ensuing invective. Stunningly, very few such pieces appeared. In March, with the publication of The Fruit Thief and Quiet Places, it will be hard to further evade that responsibility.

When I tell you that the long title essay of Quiet Places (written in 2011) begins with Handke’s memories of outhouses, boarding-school and railroad-station toilets, restrooms (especially in Japan), and so on, you may be inclined to pass. That’s fine. Despite the title assigned to my First Things column on Handke, I have no interest in pushing his books on you. But if you read the essay, in which the notion of Quiet Places is extended imaginatively well beyond its starting point, you will find that it is an extraordinary expression of one writer’s sensibility, of the distinctive way he experiences the world—“autobiographical” in the deepest sense, even as it eludes the customary strategies of “memoir.” If you dislike this essay, you are very unlikely to enjoy Handke’s fiction. If on the other hand you find it irresistible, you have a lot of good reading to look forward to.

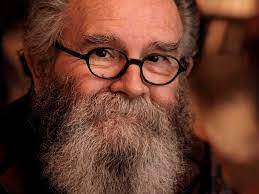

John Wilson

John Wilson edited Books and Culture (1995-2016). He writer regularly for First Things and a range of other magazines. He is a contributing editor at the Englewood Review of Books and senior editor at Marginalia Review of Books.