Why I Love Watching The Olympics

From one year to the next, the only televised sporting event I watch is the Super Bowl. But every four years, I watch forty hours of the Olympics. While I find myself increasingly skeptical that high school sports can offer athletes one-tenth of what they claim (virtue, martyrdom), the Modern Olympics have both goals and means that are quite different from the garden-variety volleyball program.

The Olympics—by which I mean the Modern Olympics, which began in 1896—are undeniably an Enlightened project, although they are touched by Romantic tastes, as well. There is something quite beautiful about the belief that bloodless sport and physical artistry could replace warfare as the primary stage upon which rival nations resolve their mutual animosities. After considering the unprecedented slaughter and barbarity of the 20th century, we should admit the Olympics have proven a complete failure in this regard, but there is nonetheless something innocent and childlike about such good intentions. Can sports replace war? No, but “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

Despite their Enlightened origins, the Olympics are still a holdover from a saner age, and so the Games have many qualities which strike me as wonderfully opposed to the present zeitgeist.

To begin with, I should say my favorite Olympic sports are the ones which are subjectively judged by a panel of experts who award points for skill and style: synchronized diving, figure skating, freestyle skiing, and most gymnastics. In an era which prizes self-expression, it is quite common for judges to yank gold from the hands of a certain gymnast or skater for failing to exactly meet mind-bogglingly specific requirements of form. While watching synchronized diving last night, I was regularly impressed by dives which left the judges cold. On replay, commentators explained how the divers had made miniscule departures from established standards—miniscule to the untrained viewer, that is, but massive to a trained eye. After ten thousand hours of training, an error too small and too brief for the average spectator to see may consign a performer to obscurity. “History throws its empty bottles out the window,” as Chris Marker once put it. Just one more hour of practice might have been all it took to win. Despite the heartless ways in which sentimentality governs modernity, the Olympics are indifferent to the physical suffering required to enter the games and indifferent to the spiritual suffering most athletes must endure when returning home. The Games would have us understand that there is something beyond our feelings.

Some might argue that diving and gymnastics (and so forth) are not unique in this, and that all sports require close inspection. After all, some NFL games come down to a final play, some NBA games come down to a final shot, and when they do, every minute action of the shooter can be criticized. However, points are awarded in the NBA for putting the ball through the hoop. It is true that some NBA players are graceful, but their grace contributes little (if anything) to the standing of the team. It does not matter how slapdash, ill-advised, or selfish a shot is provided it goes in. When it comes to figure skating, though, there is no such thing as an ugly win.

Besides this, professional athletes in America have the consolation of large fortunes, fame (even in loss), and many additional opportunities to prove themselves. Professional sports are hardly indifferent to the suffering of athletes, a fact born out in the sheer volumes of complaints pro athletes make against referees. Olympic athletes whine and complain to the judges far less than professional athletes, even though the average Olympic athlete has comparatively more on the line than a pro.

I do not mean to suggest there is no glory to be won in basketball or soccer. I could watch Gary Payton and Shawn Kemp highlight reels for hours and be edified the entire time. Still, inasmuch as every sport represents life itself, I think something like the pommel horse has a far higher degree of verisimilitude than most sports with a ball, a field, and a clock. Put another way: gymnastics is more realistic than basketball in the same way Ingres’s paintings are more realistic than Cezanne’s.

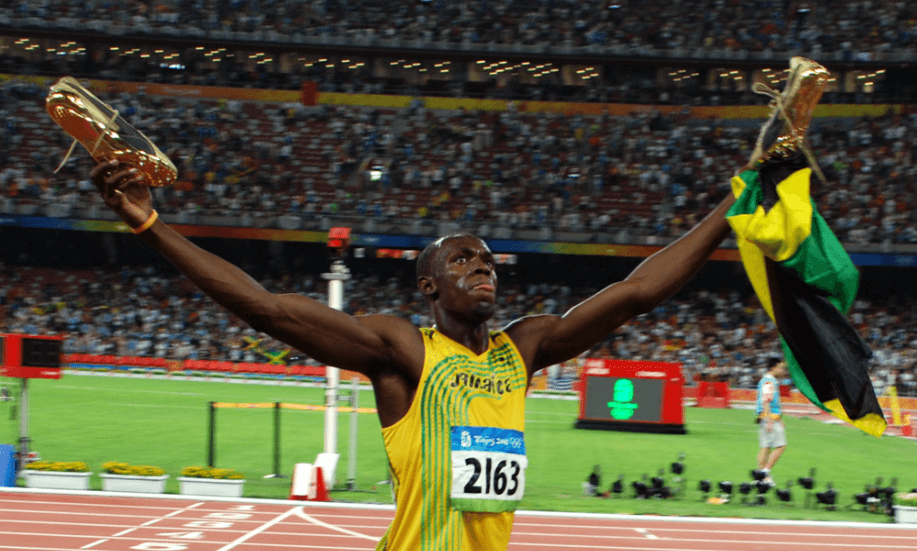

The events themselves are not all that make the Olympics the Olympics, of course. While the lines of competition are drawn between nations, watching the Games tends to produce a remarkable balance between love of one’s own people and love of others. The first sort of love seems to easily segue into the second. When watching, I intuitively pull for the United States, but I find myself easily won over to charismatic athletes from other countries. In distinguishing athletes by nation, the Games ask us to humbly marvel at the fact that people unlike ourselves are capable of besting us. What is more (what is wonderful), the Games often invite us to relish the fact others can best us. The athletes themselves lead viewers in this. When competition is properly framed, even losers feel they have contributed to the revelation of something transcendent, profitable; this revelation helps calm the tumult which attends loss.

Naturally, there are exceptions, but the graciousness with which Olympic athletes accept defeat defies a purely rational explanation. There is something mysterious about real glory—not the pursuit of a win, but the pursuit of pure form—which sublimates the ego. The Olympics are like a two-week-long version of the 1914 Christmas truce, although they are born of mutual respect for Plato, not the Nativity.

Perhaps the graciousness with which Olympic athletes accept defeat also has something to do with the fact they compete on behalf of their nations, not merely on behalf of teams or cities (where they have only lived a short time). Openly, unambiguously representing your kind of people creates a powerful and productive sense of self-awareness, and self-awareness is nothing but a desire to judge yourself accurately and others leniently.

For all these reasons, I am not entirely sure the Olympics are long for this world. I have read the Japanese will recoup very little of the $20 billion they spent hosting the games, which could make other potential host cities understandably leery of the risk. Besides this, the Olympics are split down the middle between men’s and women’s competitions, and such distinctions may not be legally allowable ten years from now. Abolishing those distinctions would quickly cut the number of events in half—but who can say whether terms like “winner” and “loser” will have a place in a future which condemns every unpleasant thing?

For the time being, I am content to show my children the Olympics on television, to blithely gloss over many of the foolish things about the Games, and to happily connect what we see to an older and largely discarded view of transcendence and beauty.

Photo credit: Jmex

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs is the director of The Classical Teaching Institute at The Ambrose School. He is the author of Something They Will Not Forget and Love What Lasts. He is the creator of Proverbial and the host of In the Trenches, a podcast for teachers. In addition to lecturing and consulting, he also teaches classic literature through GibbsClassical.com.