What School Of Rock Gets Right About Education

Movies about iconic lines of work—cops, soldiers, lawyers, doctors—don’t have a reputation for being very accurate. Likewise, most movies that are “about teachers” and reflect only the easiest and most fashionable beliefs about education. The movies with the most to say about education aren’t about education per se.

Similarly, if you get a fellow thinking about the piano lessons he took when he was younger, he’ll smile, tell of how he whined about practicing, reminisce about a recital in an old church that came off surprisingly well, and perhaps inadvertently make a few profound comments the importance of discipline and ceremony. When asked for his “theory of education,” though, the same fellow might offer nothing but hollow platitudes about “finding yourself.”

Despite appearances, Richard Linklater’s School of Rock really isn’t a movie “about education.” Sure, there’s a teacher, a classroom, a class, a principal, and a series of highly effective lessons, but it’s no more a movie “about education” than The Shining is a movie “about the hospitality industry.” As Linklater never sets out to give us his theory of education, he’s able to make some compelling, common-sense observations about education. When it comes to education, one can never have too few theories or too many observations.

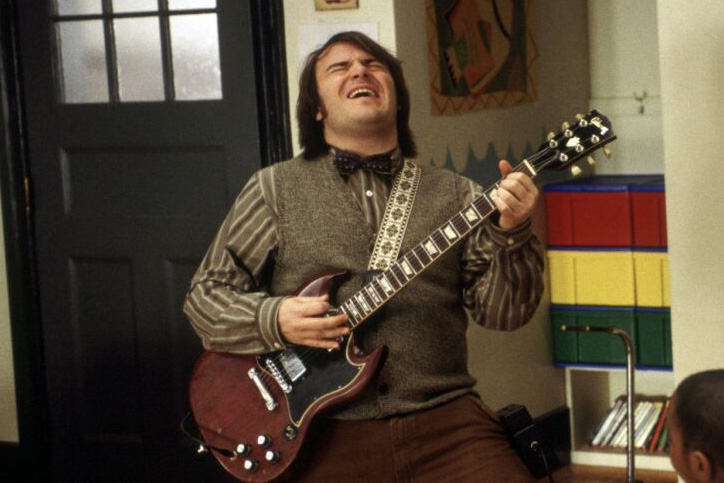

Jack Black plays Dewey Finn, an unemployed guitarist who steals his roommate’s identity and begins teaching fourth grade in a snobby private school, despite the fact most of his students are a good deal smarter than he is. Dewey does have an encyclopedic knowledge of rock and roll, though, and after discovering his students know nothing of rock, he is outraged, and decides he must teach them the one thing he actually knows—which is how to rock. Accordingly, he lectures them on rock history, plays them recordings of rock, personally performs rock for them, and shows them how to write and perform rock music on their own. All of this is done secretly, of course, because if parents knew their children were learning to do something other than get high standardized test scores, they’d be furious. Dewey’s rock class ultimately enters a local battle of the bands competition, which they lose, but all the parents are there to see it. They’re sort of impressed, and Dewey is sort of fired.

Say what you want, it’s actually far more realistic than most movies about school.

School of Rock confidently and plausibly illustrates two principles upon which every effective education is predicated: first, that the teacher is the curriculum, and second, that good teachers not only pass on their knowledge but their priorities and affections. Every young humanities teacher ought to watch School of Rock and think, “Right, so do pretty much everything this guy does, but with Socrates and Augustine, not Styx and Aerosmith.”

Dewey loves rock and roll so much, he not only wants his students to know about it, he wants them to do it, to be it. He’s not content with merely getting what he knows into their heads. He wants to get what he loves into their hearts. Consequently, the only test he gives his students is the battle of the bands, a real-world event with real-world consequences. There’s no grade on the line, but his students are still zealous to win because they want to impress their teacher, and because they want the opportunity to do what they’ve been trained to do well.

What I really love about School of Rock is that it skips the current faux-classical distinction between “teaching students how to think, not what to think,” which is impossible. A good teacher helps his students properly order their affections, which means teaching them both how to love and what to love. What point is there in teaching students how to love if they’re only going to love Nickelback and Nazism? What point is there in learning how to play stupid, ugly music? Why not teach students how to play and what to play? There is something speciously generous about the whole “how to think, not what” claim, but a reluctance to give students dogmas to live by ultimately makes them easy prey for godless college profs. People don’t love how’s, they love what’s and who’s. “How to think, not what” gives you men without chests. Sane people love people, not methods, which is one of the weaknesses of the Socratic Method. It doesn’t inspire love or devotion (for the teacher or the text). I’ve heard stories from colleagues who have visited schools that are zealously devoted to their Harkness tables wherein the teacher opens class with a question and then more or less just sits there and listens for the next hour while students pretend to hash things out for themselves. Such classrooms are aptly skewered in Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. If you don’t tell students how to think and what, they’re apt to invent lovely, sophisticated justifications for murder.

Watch School of Rock and then imagine Dewey Finn trying to make his students love rock music by asking them questions around a Harkness table. It’s absurd. He wins them over with his unfeigned adoration of his texts. He preaches the greatness of rock, he performs his love, and then invites his students to imitate him. He says, “This is what you should love, this is why you should love it, and this is how you should love it.” Classical teachers, go and do likewise.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs is the director of The Classical Teaching Institute at The Ambrose School. He is the author of Something They Will Not Forget and Love What Lasts. He is the creator of Proverbial and the host of In the Trenches, a podcast for teachers. In addition to lecturing and consulting, he also teaches classic literature through GibbsClassical.com.