What is Grammar?

Soon after moving to western Ukraine at age 19, I began language training in earnest, eventually studying under two extraordinarily different teachers. My first teacher, Tanya, spoke English. She was the consummate teacher, who turned everything into a lesson. She set out to introduce me to the beauty of the Ukrainian people and culture; she took me to the local museums and village churches and dinner parties. She made the best salat olivye I ever ate and taught me her recipe, which I still make. My second teacher, Vitally Arkadiovich, spoke no English. He was brooding and philosophical and, above all, passionate about running. He tasked me with memorizing Shevchenko poems and had me describe paintings at length in Ukrainian. He badgered me until I became a runner, and running was an extension of my lessons.

There was one thing both had in common as educators: neither could coherently explain cases. An inflected language, Ukrainian uses seven cases (noun endings that vary according to usage in the sentence). If you used the wrong case, no one would understand you. Thus, we would go round and round. “How do you know which case to use?” I would ask.

“Answer the question,” they would respond. The questions were declensions of “who” and “what”; if you knew which declension of the question to use, you already knew the case and the point was moot. These conversations always ended in the same maddening directive: “You must feel the language!” I wanted rules for a new language; they instead offered me a new home.

Normally, when we think of grammar, we think of rules about parts of speech and their usage. Historically, however, grammar was a robust art, not a syntactic abstraction. In her brilliant book, The Trivium: The Liberal Arts of Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric, Sister Miriam Joseph defines grammar as “the art of inventing symbols and combining them to express thought.”1 Fundamentally, grammar is rooted in being; it is “the thing-as-symbolized.”2 There is no separation between word and thing; for the art of grammar, you must know both.

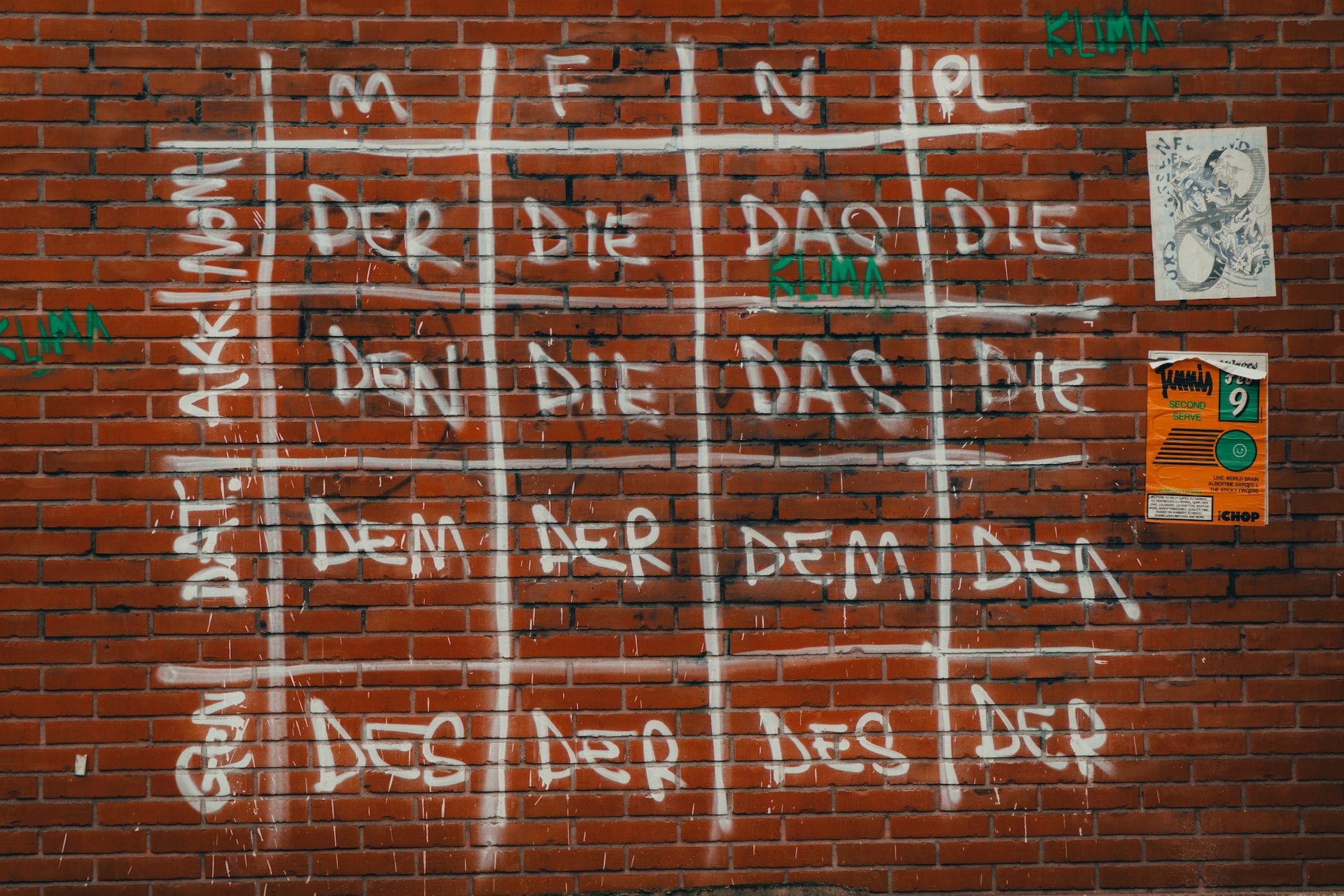

In The Liberal Arts Tradition, Kevin Clark and Ravi Jain give a more intuitive definition of grammar: it is “the art of being at home in language.” When you are at home in a language, “feeling the language” is not so crazy after all. I slowly learned the cases through lessons with a porcelain teacup accompanied by motions: this is a cup (nominative), drink from the cup (instrumental), put the saucer on the cup (locative), and so on. Gesticulating with a teacup chashka, chashkiy, chashtsiy… gave me a home in the language that abstraction alone never could have. Charts and chants are building materials, but they are not a home.

Homes are built upon a foundation. In the home of language, without the foundation of being, abstraction distorts and collapses. You must have a relationship with the thing-that-is-being-named – without that, you can learn a shadow of a language but nothing more. If we extend a sterile, modern notion of grammar across the elementary school curriculum it serves to flatten the whole of the curriculum. The common interpretation of Dorothy Sayers’s “Lost Tools of Learning” is that the “grammar of” a subject is merely the rudimentary knowledge of that subject throughout the elementary years. Clark and Jain explain the results of this misstep:

Hence, grammar education has become a kind of back-to-basics approach to learning, where Christian classical educators teach the “grammar of…” a number of subjects – history, science, mathematics, and so forth. Unfortunately, the modern curriculum goes unchallenged in the process. Our teachers feel they are recovering classical education because grammar education is more “rigorous,” by which we mean more systematic, and, more often than not, filled with more content. This “grammar of” model, however influential, is fundamentally misguided because it starts with a merely modern understanding of grammar.3

In historical classical education, the art of learning to speak, read, and write was built on the foundation of a musical education. Musical in this case means “inspired by the muses” and is distinct from the mathematical art of music in the quadrivium. In Plato’s Republic, Socrates argues that the foundation of education is gymnastics for the body and music for the soul (rooted, of course, in piety). He specifically includes story or myth as part of this musical training. This foundational step tunes the heart to the real and furnishes the moral imagination. Then your charts and chants can stand upon the context of meaning.

My musical education in Ukrainian filled my imagination. There simply isn’t a one-to-one linguistic correspondence between two languages. There were sights and smells and tastes that I had not experienced before. I had to know the thing before could join the thing to understanding through the art of grammar. For example, tvoroh translates as “cottage cheese,” but it is not. There are many words apropos fields of wheat and I could not begin to explain them in English. It is one thing to know that a babushka is an old lady; it is quite another to know the smell of a handful of babushkiy in a closed train car.

In addition to imagination, this musical education also developed my intuition, just as Plat0 promised:

He who has received this true education of the inner being will most shrewdly perceive omissions or faults in art and nature, and with a true taste, while he praises and rejoices over and receives into his soul the good, and becomes noble and good, he will justly blame and hate the bad, now in the days of his youth, even before he is able to know the reason why; and when reason comes he will recognize and salute the friend with whom his education has made him long familiar.4

I memorized things before I could join them to reason: declensions, children’s rhymes about samovars, Taras Shevchenko’s “The Mighty Dnieper,” and song lyrics in church. I began to distinguish between the Transcarpathian village dialect and literary Ukrainian. The language began to sound right or wrong to my ear. And, eventually, Ukrainian became a new home.

1 Sister Miriam Joseph, The Trivium: The Liberal Arts of Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric, ed. Marguerite McGlinn (Paul Dry Books, 2002), 3.

2 Ibid, 9.

3 Kevin Clark and Ravi Scott Jain, The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Philosophy of Christian Classical Education (Camp Hill, PA, Classical Academic Press, 2019), 52.

4 Plato, Republic, 3.402a.

Rachel Woodham

Rachel Woodham has a BA in Russian Language and Literature and is a graduate student of Great Books at Harrison Middleton University. A classical educator for the last decade, she now homeschools her three all-time favorite students.