No products in the cart.

What Faustus and Voldemort Can Teach Us about Humility

With a smartphone in hand, our students have access to piles of information. Just google it. Don’t know much about your final exam question? No sweat: ask a chatbot to come up with an essay. You might fool your teacher or your parents. The person you fool the most is yourself.

Literature is full of characters who were sure they could be the smartest person around. That’s not just pride, which can be a virtue, but what the ancient Greeks called hubris—overwhelming arrogance that you’re the top dog in whatever field you choose. What you are missing is humility. You don’t know what you don’t know—and so you don’t know when you’re reaching a bit too far for your own good. Let’s have a look at two literary examples to learn the lesson.

Meet Dr. Faustus, sometimes called just Faust. He was a medieval alchemist who, looking to be the greatest scientist in the world, sold his soul to the devil to achieve fame and wealth. The stories are based on a real person (maybe two) who died in the middle of the sixteenth century and is alternately referred to as an astrologer, a necromancer who can speak with the dead, an occult magician—you name it. His name appears in a German Faustbuch, a 1587 collection of tales, among actual medieval scientists like Albert the Great and fictional wizards like Merlin. The tale quickly gained attention and was translated into several languages, which led to other authors running with the stories. There were manuals exchanged in dim corners of pubs, cellars, and macabre laboratories supposedly based on his incantations to perform tricks, miracles, and black magic among them summoning and trying to outsmart the devil.

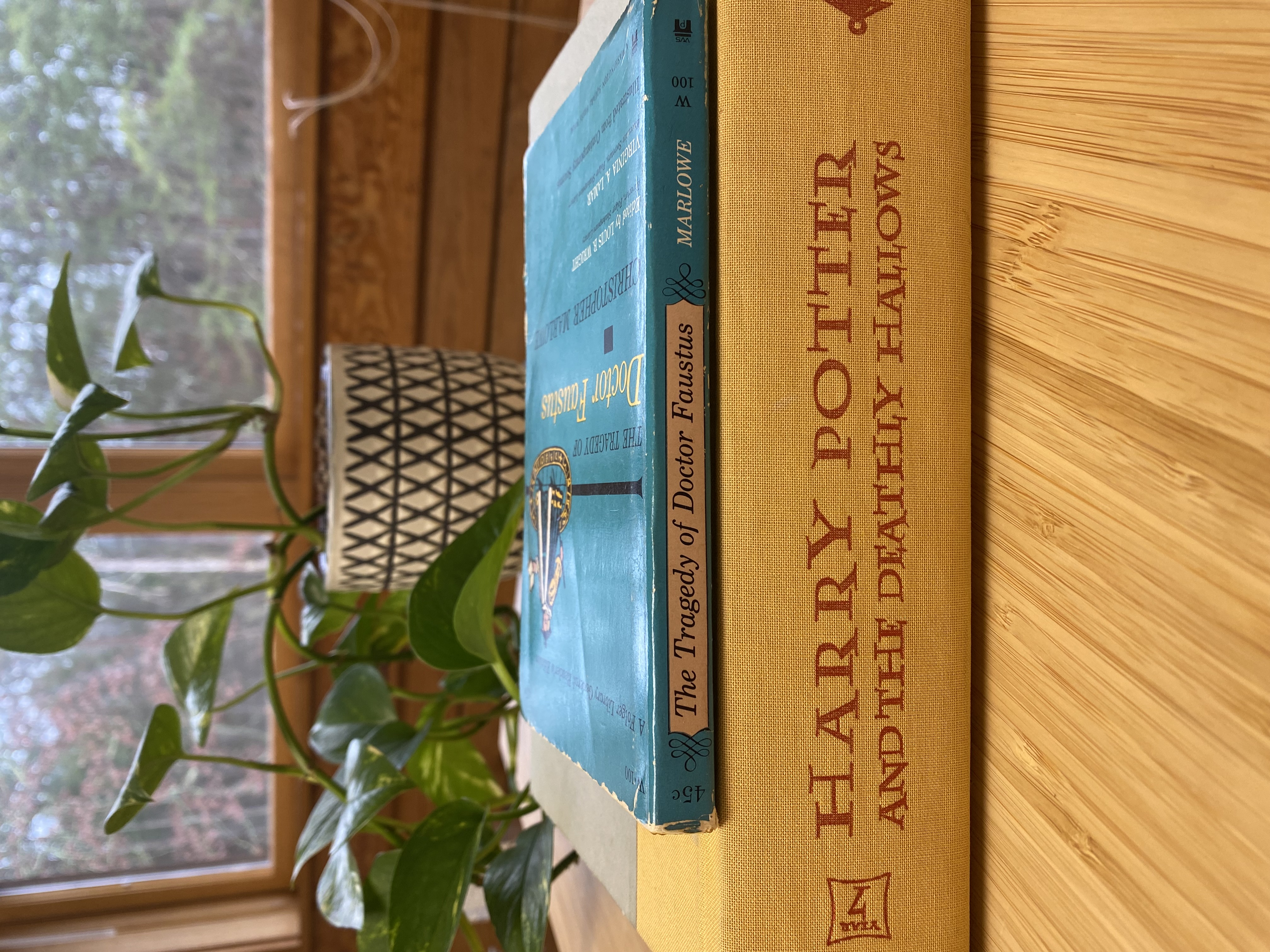

A very influential telling of the Faust tale was written by Shakespeare’s contemporary Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593), himself a tragic person whose great talent ended early: he was stabbed to death in a barroom brawl before he turned thirty years of age. Marlowe, a playwright, wrote a Tragical History of D. Faustus that was performed around the end of his life. In an almost comical scene, two angels appear to the doctor who is bored and unsatisfied with his studies. The good angel urges him to be content, but the evil angel entices him with a promise: Faustus has the chance to be the most learned man in history.

He strikes a deal with Mephistopheles, acting as Satan’s agent, for twenty-four years of power via sorcery. The contract is signed in blood. Mephistopheles delivers books about the heavens and earth, which both attract Faustus but also needle him. Several times throughout the play, the good angel reappears to try to get Faustus to turn back, but every time he gives in to the bad angel’s enticements and continues in his devil’s pact. Who wouldn’t when Mephistopheles takes him on a tour of the world in a chariot pulled by dragons? In the end, Marlowe’s Faustus regrets the deal, but it’s too late. Mephistopheles comes to drag his soul to hell, leaving the Chorus, which in ancient Greek theatre speaks the wisdom that our conscience should have in guiding our actions. They conclude the play after Faustus has met the doom he had prescribed for himself.

Cut is the branch that might have grown full straight,

And burned is Apollo’s laurel-bough,

That sometime grew within this learned man.

Faustus is gone: regard his hellish fall.

Whose fiendful fortune may exhort the wise,

Only to wonder at unlawful things,

Whose deepness doth entice such forward wits

To practice more than heavenly power permits.

A frightening yet accurate epitaph.

The German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) wrote a version of the story, although Goethe’s ends with Faust’s redemption—a surprise given how deeply Faust has drunk of greed, passion, fame, and money offered by the devil’s enticements. Operas, plays, poems and songs, ballets, paintings and sculptures, novels and short stories followed, sometimes as in Marlowe’s version with Mephistopheles (or Mephisto) playing on Faust’s ambition and drawing him to damnation. There are editions in the middle of the twentieth century tying Nazism and Fascism with the devil’s bargains. People conspire with the devil to advance themselves at the expense of others just as so many had done with Hitler and Mussolini. All of these elements come together in Klaus Mann’s novel Mephisto (1936), made into a 1981 film, in which an actor plays Goethe’s Mephistopheles, attracts Nazi attention, and collaborates with them to advance his career.

We also hear echoes of hubris in the Harry Potter books and movies where it seems that Faust and the devil are one and the same. Tom Riddle leaned into evil wizardry, transforming himself into the dark Lord Voldemort and making the foreboding Hogwarts course, Defense Against the Dark Arts, a critical one for the inevitable final conflict. In the climactic scene of the seventh novel, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Voldemort’s ambition is destroyed by Harry Potter, but it’s Voldemort’s hubris that causes his own downfall at the point of Harry’s wand.

Voldemort is sure he’s a better wizard than even Dumbledore. There’s no way Harry knows a secret he doesn’t. There’s no need for remorse. Voldemort had broken up his soul in pursuit of domination, placing the pieces in horcruxes that he was certain would ensure his survival. (For you muggles—non-wizarding folk—a horcrux is an enchanted object.) But once all those horcruxes were destroyed, he was vulnerable to Harry. Yet he’s the instrument of his own defeat: Voldemort’s curse at Harry rebounded to himself. He died as the broken shell of Tom Riddle.

Faustus and Voldemort learned the hard way that choices have consequences. They could have done much and done well if they had just a little humility.

Christopher M. Bellitto, Ph.D., is Professor of History at Kean University in Union NJ. His latest book, from which this essay is adapted, is Humility: The Secret History of a Lost Virtue (Georgetown University Press, 2023).

Christopher Bellitto

Christopher M. Bellitto, Ph.D., is Professor of History at Kean University in Union NJ. His latest book, from which this essay is adapted, is Humility: The Secret History of a Lost Virtue (Georgetown University Press, 2023).

1 thought on “What Faustus and Voldemort Can Teach Us about Humility”

Wonderful and insightful!