The Worst Super Bowl Halftime Show Ever (And Why It Matters To Classical Teachers)

When you think about the turn of the last millennium, you probably remember that whole Y2K thing, but there was another issue that troubled mankind during the leadup to January 1, 2000. It wasn’t nearly so vexing as the potential collapse of civilization, though I still think it fair to call it “a problem.” I’m referring to the question of how to thematize a millennium celebration.

Let me explain.

A Christmas party is easy to thematize. You decorate your home with red and green, play Nat King Cole records, and serve eggnog. A 4th of July party is also easy to thematize: burgers, sparklers, American flags, Coors, and Tom Petty on the hi-fi. Halloween parties and birthday parties are easy, too. But what’s the aesthetic for a millennium celebration?

No one really knew.

It couldn’t merely be a nicer version of a standard New Year’s Eve party. The New Year’s Eve aesthetic is thin because no one puts all that much preparation into it. The turn of the millennium, on the other hand, was a thing people talked about constantly for several years before it actually happened—and after it happened, people kept celebrating it for many months (or longer).

Most holidays are concerned with beginnings and endings. Christmas is the birth of Christ, Good Friday is the death of Christ, Easter is Christ’s “birth” from the dead. Pentecost is the birth of the Church. This is true of secular holidays, too. The 4th of July commemorates the birth of our nation. Bastille Day in France celebrates the beginning of the end of the ancien régime. The New Year’s aesthetic isn’t all that pronounced, though, and while there’s nothing sober about the average New Year’s party, the New Year’s mood is often hesitant and unsettled. Unlike the birth of a confirmed hero or saint, the birth of a new year isn’t necessarily a good thing. Some years are better than others, after all, and we don’t know what kind of year the new one will be.

The millennium aesthetic couldn’t be hesitant and unsettled, though, because it had to go on for a long time. But what exactly was the millennium a celebration of? It wasn’t political. It wasn’t religious. Perhaps it could be a celebration of the human spirit, something that cut across religious and political lines—but the Olympics already had dibs on that, and the marking of the millennium had no inherent connection to the human spirit. The Olympics actually involves people from many nations congregating in one place to pursue excellence and camaraderie. The millennium was nothing like that. There was a very real sense in which the millennium was nothing more than a celebration of the moment a bouncing DVD player logo hits the corner of a TV screen. The logo in question hadn’t hit the corner in nearly a thousand years, so there was understandable excitement, but describing the moment it was going to hit in sentimental terms almost always came off as mock-heroic.

Looking back now, Y2K fears in the late 90s were a bit of a godsend, for they invested the forthcoming millennium changeover with a gravity that would have otherwise been entirely absent. Y2K fears covered over the fact the millennium was an empty event that people wanted to be meaningful simply because their lives were so bereft of meaning.

In the end, it’s fair to say the aesthetic of the millennium was “global,” by which I mean an undifferentiated amalgam of disparate cultures, especially those cultures which HR directors count as “diverse.” This millennium aesthetic is present in any number of big cultural events from 1999 and 2000, but for my money, it is easiest to see in the 2000 Super Bowl Half-Time Show, which I think the worst of all time.

Before saying anything about this, please note that people cheered loudly at the conclusion. It is safe to say—given the law of averages—that many Americans went to work on Monday morning and commented to their coworkers around the water cooler, “The Halftime Show was amazing.” A number of benighted souls may yet be found (in the YouTube comments section) praising the work for its generosity and goodwill.

Nonetheless, nearly every online media outlet which has put forward an ordered list places the 2000 Halftime Show near the bottom. The reasons for its badness are legion, though many critics note the show’s exceedingly vague optimism has “aged poorly.”

“The future is coming

We’ve got to catch it if we can

The magic’s unfolding

You can hold it in your hand

We can touch tomorrow today

To make some memories

That will never fade away.”

-from “Celebrate the Future, Hand in Hand”

In retrospect, celebrating “the future” in the year 2000 was a painfully naïve thing to do. I can’t help but imagining Osama Bin Laden, already knee-deep in 9/11 plans, watching the show and shaking his head bemusedly as a lacky translated the lyrics for him. Even if it weren’t for the forthcoming World Trade Center attacks, nearly everything said in the show is calculated to either be so perfectly vacuous and noncommittal that no human being could possibly disagree, or so bafflingly stupid as to render speechless anyone who wanted to disagree. “The future is coming/We’ve got to catch it if we can…” Yeah? Are you sure? What happens if we don’t catch the future? Should I be practicing? Do I need to go anywhere in particular to catch the future or can I do it from here? Will catching the future cause any swelling or rash and, if so, would it best to wear protective gloves?

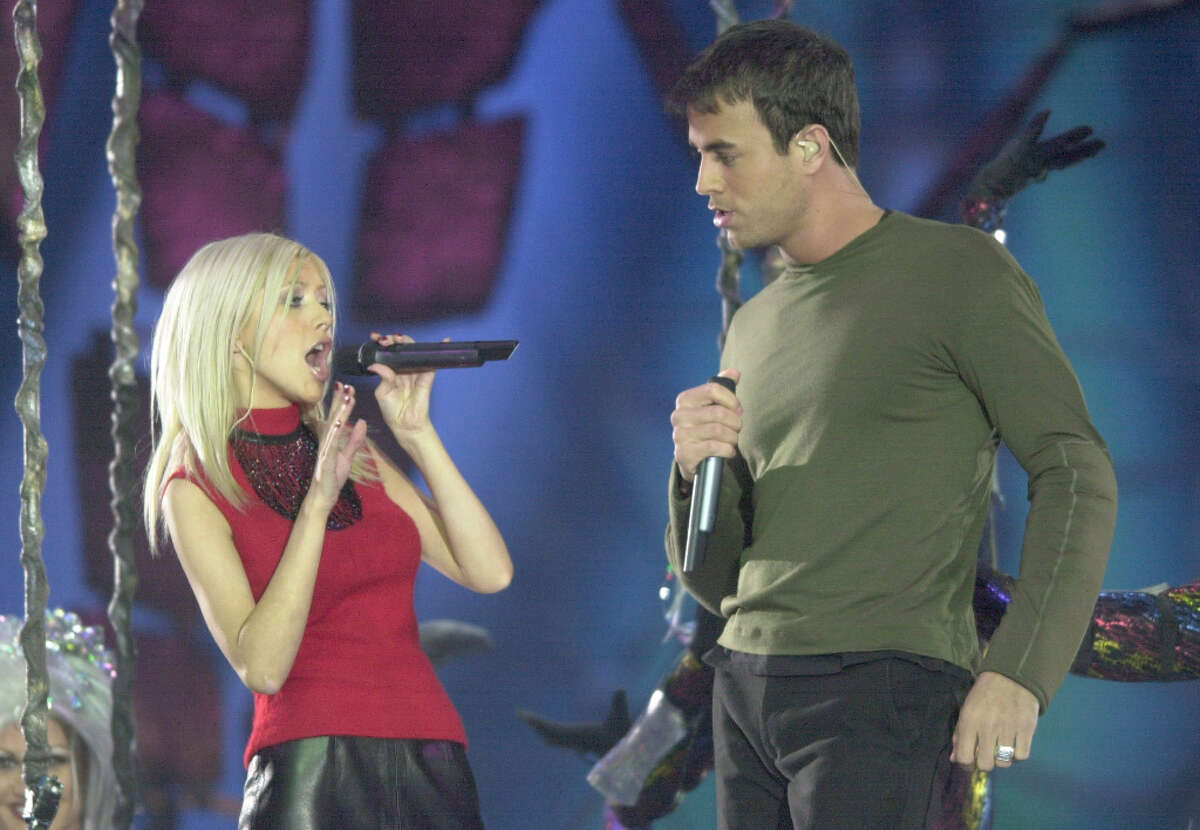

The daffiness of the lyrics to Christina and Enrique’s song are partially covered over by the music. Narrator Edward James Olmos isn’t so lucky, though. He has to speak the following lines in the relative nakedness of prose:

The sage of time has returned

To rekindle the human spirit

And lead us in an earthly celebration

That unites the world.

Once again as it does every thousand years,

The gateway of time has reopened

Giving us hope for a better tomorrow.

While I am given to jeering at self-affirmative aphorisms like, “Believe in yourself,” and, “Follow your dreams,” such sayings are coherent enough to inspire shaky self-confidence in the shallow and gullible. However, the idea that “the gateway of time” reopens “every thousand years” sounds like a stray fact recited by an unwashed stoner who won’t leave you alone on a city bus. Apparently, the gateway of time is currently closed, which means there’s no hope now for a better tomorrow. It will open again in 975 years. Until then, dunzo.

As for the “earthly celebration that unites the world,” was there no middle school English teacher around to proofread this? Perhaps even a middle school English student? I suppose the budget was tied up in the furry snail helmets the drummers wore. But let me make sure I have this right: it’s “an earthly celebration that unites the world”? You’re quite sure you need the word “earthly” in there? You don’t think it’s sufficiently implied that a celebration which “unites the world” must necessarily be earthly? That really needs to be stated? If so, would it be best to clarify the idea just a little further by saying it’s “an earthly celebration that unites the earthly world”? Overkill? If you say so.

The badness of the show is easy to see twenty-four years later, and yet it’s not exactly true that it has “aged poorly.” Raw meat ages poorly, but the 2000 Halftime Show was quite, quite rancid on the day it aired—and this was obvious at the time to anyone who had even a modicum of good taste. The passage of time makes it easy for everyone to see the stupidity of stupid things, but a wise man can see that foolish things are foolish immediately. A fool judges a foolish thing foolish only after it becomes popular opinion. By the point a foolish thing is commonly thought foolish, though, it has already done its harm. The people who needed twenty-four years to see the 2000 Halftime Show was stupid are going to need another twenty-four years to see the stuff they like today is stupid.

The question, then, is this: how do you acquire the ability to see things here and now with the perspective that twenty-four additional years grants? How about the perspective which fifty more years grants? How about a hundred?

For starters, one has to be familiar with things that last. The modern man who has not heard a lot of old music, read a lot of old books, or performed many years of back-breaking labor is ignorant of the effects of time. A man cannot know what will last unless he knows what has lasted.

Similarly, one must know all the disguises by which stupid things regularly cloak their stupidity: sex, spectacle, excitement, expense, speed, shock, popularity, blasphemy, obscurantism, and disgust. The 2000 Halftime Show attempted to hide its stupidity beneath a bullying insistence on the millennium’s importance, despite having absolutely no evidence to back this up. Twenty-four years later, claims of the millennium’s importance never panned out and viewers have nothing with which to distract themselves from the artistic emptiness of the performance. But none of the cloaks for stupidity last all that long. Skirts get shorter, speeds get faster, budgets get bigger, and last year’s distractions from stupidity fail.

We take comfort in the idea that taste is subjective, and yet the stakes are surprisingly high. An inability to discern what will last condemns a man to unwittingly feed his soul stupid things. And you are what you eat.

The long view cannot be acquired merely by knowing history, though. One must also know how to interpret history, a skill which only comes by paying very close attention to how people act, how they talk, how they think, and whether they ultimately turn out happy or not. A right understanding of history is bound up entirely in the ability to draw connections between seemingly disparate moral and aesthetic elements of a friend or coworker’s life. Apart from this, the wise men and fools of history have nothing to do with us. They are meaningless.

In its emphasis on beautiful old things, a classical education offers students a place to stand from which the present can be viewed in the broader context of time. We don’t study history to keep from repeating it. Yes, there were many mistakes made in the past—I might even say the lion’s share of history is comprised of damnable mistakes. And yet, the past also contains many things worth repeating, and these are the things which make up the content of a classical education. In this, we study the past to keep from being swept along by the torrent of fashionable, well-disguised stupidity which courses through the world today.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.

1 thought on “The Worst Super Bowl Halftime Show Ever (And Why It Matters To Classical Teachers)”

Two responses to this wonderful response to an emptiness:

1. Will President Clinton ever apologize for building a “bridge to the future.” Maybe the bridge went to the wrong island…

2. During the Enlightenment, western intellectuals famously stopped believing in a cosmos with an internal harmony. In varying degrees they replaced it with chaos, which finally “won” in the post-modern era.

The trouble with chaos is that we can’t stand it, not to mention that we can’t survive it. So we have no choice but to impose order on it.

The trouble with imposing order on chaos is that whoever is best at it comes out on top. But then, when they do, they are not restrained by any order already located within the chaos. They are universally adored for bringing order out of chaos, but there is nothing to guide them apart from their own imposed order.

In other words, the logic of the situation and the terror it generates require tyranny.

During the transition to that tyrannical mindset, we express our lostness in a brief celebration of the emptiness, for the most part because emptiness feels freer than conforming to an external harmony. We think of the future as a thing with a warm and embracing personality because we decided that is what it is. Because anything else is too terrifying to consider.

But an empty future is more easily filled by a monster than one filled with promises.

2000 embodied the emptiness into which those tyrants poured with ever greater ingenuity and appreciation.