Teaching Students To Handle Stress

The mitochondria is having a moment.

No, you read that right. The mitochondria.

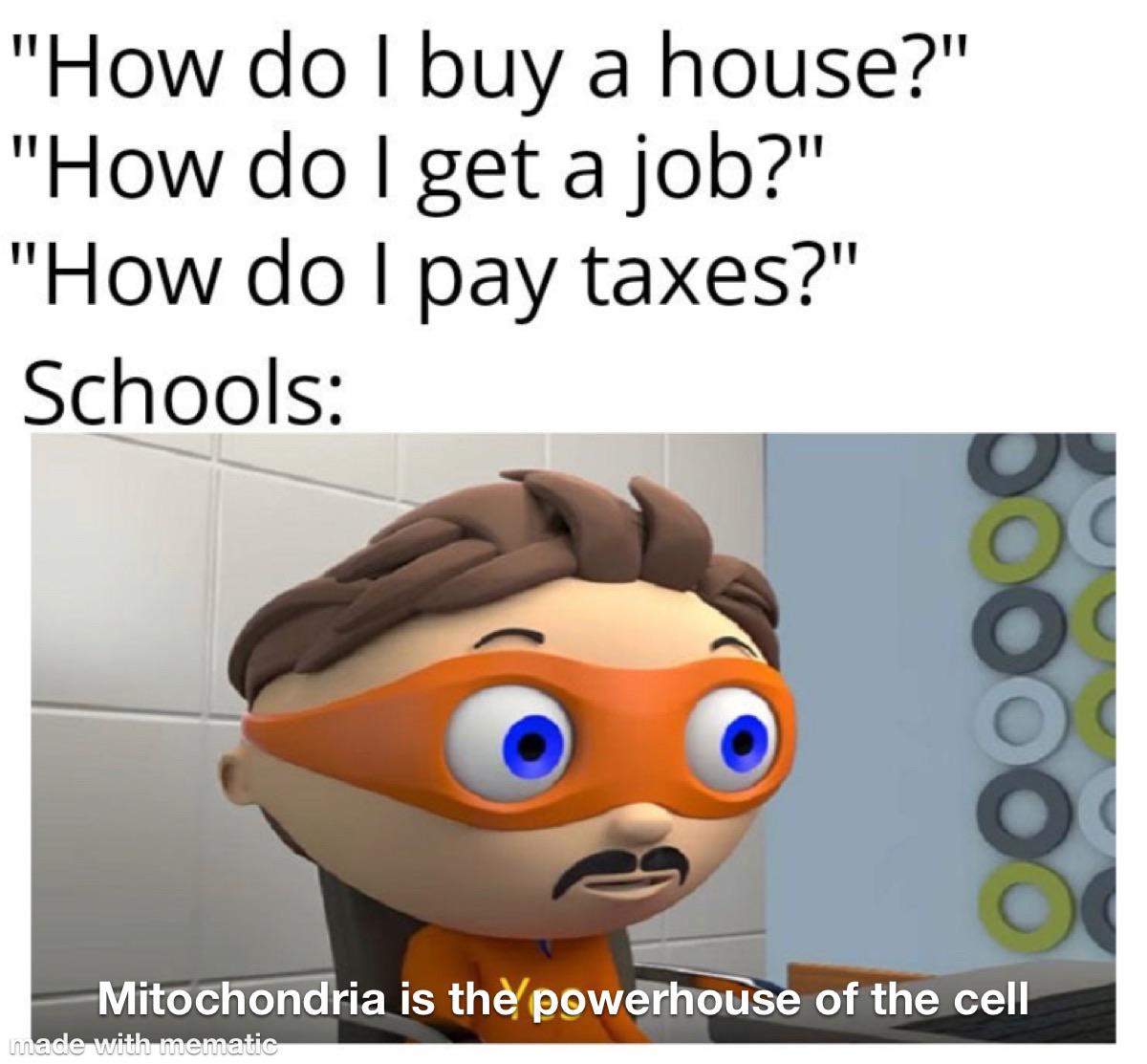

You may recall hearing about the mitochondria in a high school biology class. Actually, many people recall hearing about it, which has given rise to “The mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell” memes. The joke is that many people remember hearing “The mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell” in biology class ten years ago, but since then, this stray fact—while oddly memorable—has proven utterly worthless. Since graduating, not once have we been asked about the mitochondria. Not in a job interview, not on a date, not by a priest after hearing our confession.

The memes suggest that high school teachers might have spent their time offering students more helpful instructions on negotiating the adult world, but they instead wasted our valuable teenage hours on useless esoterica. While I have nothing against biology (and these memes could have just as easily concluded with “The Battle of Hastings was in 1066”), I appreciate the joke because it expresses a reasonable frustration that school wasn’t really preparation for adulthood.

This said, one of the most important ways teachers can prepare high school students for the adult world is by helping them think reasonably about stress and giving them realistic expectations about stress. However, in our cultural moment, teachers are nearly forbidden from doing this. Instead, many parents treat teenage stress like a malignant cancer that needs to be surgically removed as soon as it is identified.

While it is a matter for a separate article, on the question of stress, let me begin by saying that I don’t assign much homework. I don’t like homework, truth be told. As a lit teacher, I prefer to do all the reading in class. At this point in the school year (late March), I have assigned a grand total of two papers for my humanities students, neither more than a thousand words long. My reticence to assign homework has everything to do with my belief that teachers should get full usage out of all their class time and that a good class is one which cannot be made up if missed. When students tell me they are going to miss tomorrow’s class and ask what they can do to make it up, I often tell them, “You can’t make it up. Your loss is irreparable,” and I’m not exactly kidding. I want my students to live rich and interesting lives outside of class—and even if they’re not going to do that (because of their devotion to TikTok or video games), I want to treat my students like my own children, who do live rich and interesting lives outside of class.

Despite giving so little homework, on the rare occasions that I do assign papers, parents and students complain that I am stressing them out. It hasn’t always been this way, but a good deal has changed since I began teaching seventeen years ago.

If you’re not a high school teacher, you might not appreciate the extent to which the fear of stress now dominates the academic landscape. What is true outside of school is true inside, as well, and stress is the great villain of our time. It is the root of all evil, all mental and physical health problems. Teachers hear quite a lot from parents and administrators about stress. Homework is stressful. Grades are stressful. A packed schedule is stressful. Even going to class is stressful—so stressful, in fact, that most teachers have a few students who occasionally skip school just to stay home and unwind. The “mental health days” that were a joke twenty-five years ago have become a dire medical necessity. Of course, skipping class makes those students get behind on their work, and getting behind on their work is stressful, too, hence skipping class now creates the need to skip class later.

Still, there seems to be a growing conviction that nothing is worth stress. If learning a new skill or a acquiring a new discipline entails stress, it’s not worth it. Likewise, the need to remove all stress from the Christian life is what now drives our theology of salvation, good works, piety, fasting, confession, and so forth. The fact you’re a Christian doesn’t mean you have to do anything—because having to do things is what stresses people out. Grace means there’s no such thing as a spiritual duty.

The belief that stress is evil sets parents on a collision course with teachers, who cannot help stressing their students—and by stressing them, I simply mean requiring them to do difficult things they may or may not be able to accomplish. No discipline is pleasant at the time and unpleasant things tend to be stressful.

In their favor, parents might be forgiven for the belief that a classical Christian school will not stress their children because of how often prospective parents hear that a classical education is one which will “nurture” their children, help them “grow,” and “cultivate” virtue in their souls—all words which borrow from gardening metaphors. And what gardener ever stresses his plants out? What gardener asks his flowers to do anything difficult? Heavy reliance on gardening metaphors has lulled parents into thinking a classical education is one which is entirely affirming and pleasant.

Complaints about stress levels at school most commonly occur when a number of due dates converge on a single week. If a certain four-or-five-day period involves turning in an essay, a lab report, two quizzes, and a test, the administration is going to start hearing about it. I will readily concede that most teachers assess way too often, but that fact is entirely separate from a convergence of due dates. Ask anyone over thirty: a convergence of due dates is simply part of adult life. Every so often, one of those weeks rolls around—a sick child, a car in the shop, a plumbing problem that can’t be ignored, an anniversary dinner to plan, and two presentations to give at work. The law of averages typically spaces these duties out over a month or more, but from time to time, they all land in the same two inches of calendar space. And parents and teachers can either train students to handle the stress which comes from a convergence of due dates, or they can train students to not be dependable under those circumstances.

When I speak of “training students to handle stress,” I am not referring to some special class or elective. I simply mean teaching students that—contrary to what the spirit of our age would have us believe—stress is not the root of all evil. In fact, stress is often the root of productivity. Stress can be a helpful drive to get things done. Stress helps people to lose weight, quit smoking, meet deadlines, earn a living, and better themselves in six dozen other ways. There are even slothful, unproductive people (whom the Old Testament writers unsentimentally refer to as “useless fellows” or “sons of worthlessness”) who need more stress in their lives. Losing weight is stressful, for the time it takes to exercise puts a crunch on other activities but needing to lose weight is even more stressful. Quitting smoking is stressful but living with high blood pressure is more stressful. Meeting deadlines is stressful, but not meeting deadlines is more stressful. There’s no such thing as a life without stress. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t, which means treating stress like a problem that can be done away with is pure nonsense.

As opposed to trying to live without stress, it would be better to say we get some choice over what kind of stress we have. We may choose the stress which comes from having to write a paper or the stress which comes from not knowing how to write a paper. We may choose the stress which comes from going to class or the stress which comes from not going. There’s the stress of marriage or the stress of wishing you had married. We can have the stress which comes from a periodic convergence of due dates, or the stress (and depression) which comes from knowing others can’t rely on us when the going gets tough. Productivity comes with its own stress, but so does unproductivity. You cannot have your cake and eat it, too.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs is the director of The Classical Teaching Institute at The Ambrose School. He is the author of Something They Will Not Forget and Love What Lasts. He is the creator of Proverbial and the host of In the Trenches, a podcast for teachers. In addition to lecturing and consulting, he also teaches classic literature through GibbsClassical.com.