A School Named Sue: How Should We Name Classical Schools?

You can learn quite a bit about the classical Christian movement by looking at the way we name our schools. Every time a new issue of The Classical Difference shows up in my mailbox, I find myself leisurely perusing the list of ACCS member schools toward the back. Much like Christian businesses and parachurch groups of the last twenty years, classical schools tend to be named after concepts. There are a lot of Covenants. A lot of Heritages. A lot of Paideias. At present, twenty schools are named Veritas, although I could swear there were only seventeen when I counted last year. However, relatively few classical Christian schools are named after human beings.

Even fewer are named after acknowledged saints. There are four schools named after “Augustine,” and only one school named after “St. Augustine.” As of today, there are only thirteen “St. So-and-So” ACCS member schools. That’s around two percent.

Why are so many classical Christian schools named after concepts? Well, concepts are far less divisive than people. Consider how many statues have been torn down in the last several years, and how many places named after people have been renamed. Classical Christian schools tend to talk quite a lot about how they are “families” and “communities,” and there is something far more institutional about a personal namesake. After all, foundations and institutes are more likely to be named after men than classical Christian schools are (The Acton Institute, The Cato Institute, The Bradley Foundation, and so forth). The hesitation among classical Christian schools to style themselves as institutions, though, often creates ambiguity about who is in charge. These days, “family” is a very ambiguous concept. The modern family prides itself on having no clear-cut leader. Ask self-professed conservative moms and dads who is in charge and you’re apt to get a TED talk about gender roles, and then to hear they run a “child-centered household.” If any school calls itself a “family,” thoughtful parents should inquire, “What sort of family?”

I have my suspicions that the lack of classical schools named after people is based on three things. First, trends in Christian culture ten to fifteen years ago, when a great many classical schools were opening. Second, the fact that classical Christian schools care too much about worldview and talk too much about “teaching kids how to think, not what to think.” Naming a school after a concept neatly fits in with a worldview/how-to-think fixation. And third, the fact there is just a bit of an anti-clerical streak which runs down the middle of the classical Christian movement. If you were to ask the average headmaster why so few classical schools are named after saints, you might very well hear something which began, “Well, we’re Christ-centered, not man-centered…” I don’t need to go on because you know exactly what that speech sounds like.

What’s odd, though, is that many of the schools that are “Christ-centered, not man-centered” have a house system, and each of the houses is named after a famous saint, not a concept. At the same time, it is amusing to imagine a school which named its houses after theological concepts. Imagine hundreds of spectators standing around a volleyball game and shouting, “Let’s go, Total Depravity!” What would the Total Depravity House crest be? A martini glass and syringe, perhaps. I digress.

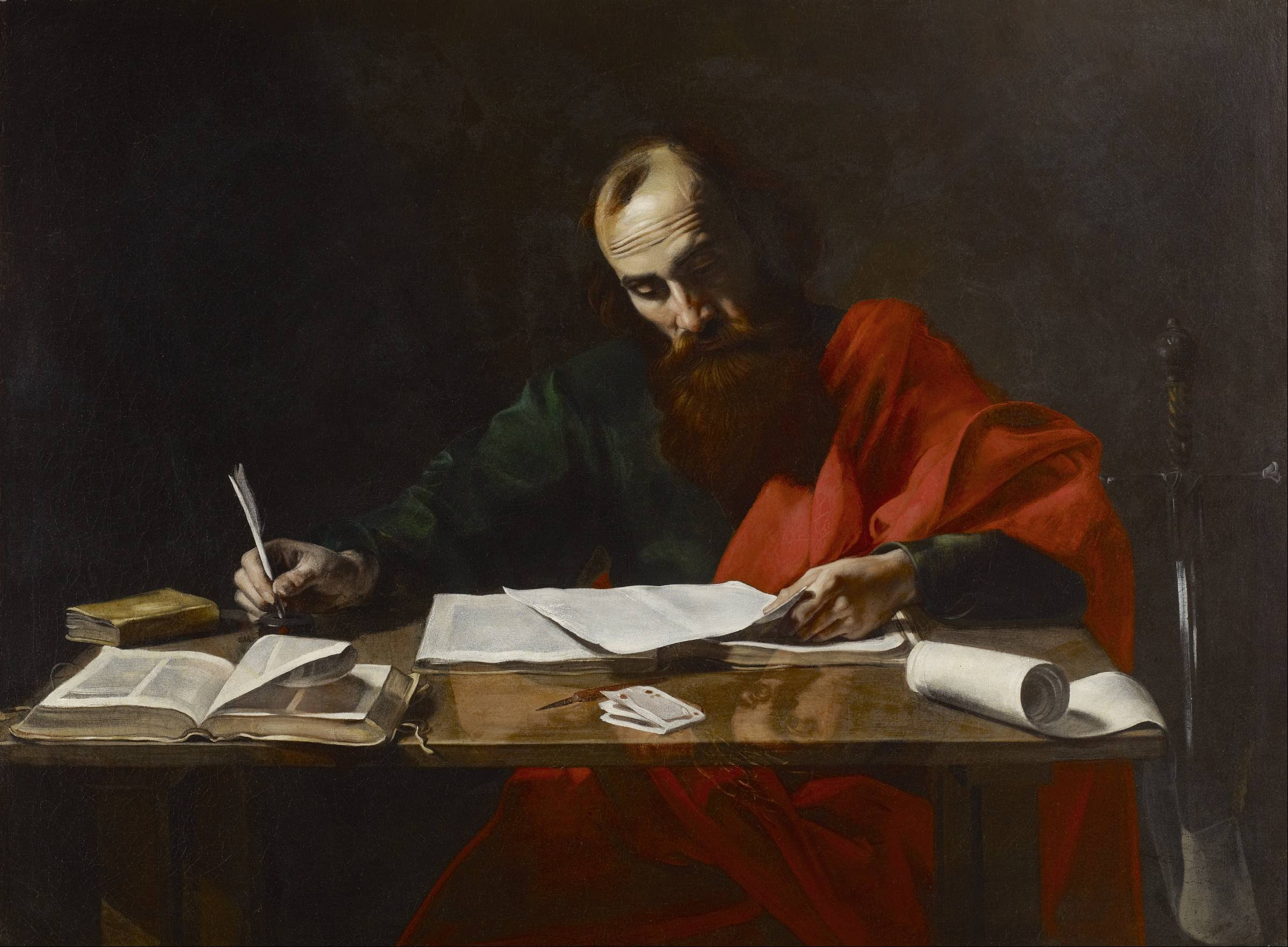

The reason houses aren’t named after concepts is that sane people don’t actually love concepts. Concepts don’t really inspire loyalty. People love people. People can be imitated. Concepts can’t. You really want the students in St. Lawrence’s House or St. Peter’s House to have the faith of St. Lawrence or St. Peter. The faith of St. Lawrence is a definite, particular thing which can be read about in history books. When I asked my sophomore students why they thought so many classical schools were named after concepts, several suggested that naming schools after saints was “sort of Catholic,” which is—if it is true—a bit strange, given how many Presbyterian and Lutheran churches are also named after saints, and given the tendency of robust Reformed communities to name their think tanks, auditoriums, meeting houses, and libraries after people like Knox, Calvin, Tyndale, and Wycliff, if not Augustine and Anselm and St. Andrew, too. All this to say, the pope is very Catholic, and purgatory is pretty Catholic, but naming things after people is actually quite common to most Christian traditions.

I don’t mean to make the issue of names into a big deal, of course, because there are plenty of “St. So-and-So” schools out there which have condom machines in the boys’ bathroom, and there are also plenty of schools out there with names like Milquetoast Community Values Academy which hire qualified, brilliant teachers and allot twelve weeks for seniors to study Plato’s Republic. Neither am I suggesting that schools which are named for concepts should change their names—there are far more important things to change—the amount of class time lost to sports, for example, or the overabundance of lately published theology books in the curriculum. Besides, Veritas and Heritage and Providence are all sufficiently handsome names for schools. However, all things being equal, I believe St. So-and-So’s School is a better name than Abstract Concept School or Greek Vocab Word School.

Why?

Like all modern movements, classical Christian education is subject to trends, which means that classical concepts (buzzwords) thought cutting edge this year could be cold product by the end of the decade. Naming a school after a concept is far riskier than naming a school after a saint. While it’s easy to change the school logo, redesign the website, and revamp the mission statement, it will prove far more difficult to escape a name like “Cross Life Classical School” once people decide the name is hopelessly stuck in 2006. Classical Christian education has gotten popular enough that we’re probably only a few years away from naming schools Lift, Summit, Impact, Sponge, or whatever church names are fashionable at the time, but fashionable churches—and their names—don’t last. They emerge on enthusiastic waves of popularity and are forced to adapt or die twenty years later, but by that point the founders are too old (or wise) to hook young people (their core demographic), and some even younger, sexier church across town is already dialed in to the most current fashions. While The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill was a smug, zeitgeisty pot calling the kettle black, it was a compelling account of how churches are not immune from trends. By that, I mean that in twenty-five years there will be a podcast called The Rise and Fall of The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill, and twenty-five years after that there will be a podcast called The Rise and Fall of The Rise and Fall of The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill.

A good many classical Christian schools already style themselves after megachurches. They talk about “taking over this city for Christ,” have dope Instagram accounts, bring motivational speakers in for assemblies, won’t shut up about “the culture,” and are generally one pair of Air Jordans away from getting sued by Stephen Furtick for copyright infringement. If a classical Christian school is going to last, it must unapologetically attach itself to something with baggage. Baggage is ballast. Concepts don’t have baggage like people do. If prospective parents can handle the baggage, they won’t jump ship when trends change. For all those readers who are presently involved in starting a classical Christian school, let me highly exhort you to not name your school after something abstract, but rather to name it after somebody who confronted the world, spoke the truth boldly, and died (violently) a long time ago. Your school doesn’t need to be a trailblazer, it doesn’t need to “sing a new song.” Your school needs to formally, officially look up to someone. Your school needs to hire teachers and graduate students who are followers and imitators of saints. You need a namesake who would be embarrassed to see the young ladies dress like influencers for the spring formal, a namesake who would slap the young men in the back of the head for not singing robustly at chapel, a namesake who would ask why eighth graders were leading Bible studies, a namesake who would curtly remind teachers to “make the best use of their time because the days are evil” every time they piddled class away on study halls or four-on-a-couch. Leaders in classical Christian education need to carefully consider the Puritan proverb, “Religion begat prosperity and the daughter devoured the mother,” and then make long, exacting, uncomfortable lists of what it would look like if the present prosperity of classical Christian education devoured the religious zeal it was founded on twenty to forty years ago. There is no money to be made in the authoring of such a list, but much treasure in heaven.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.