Rhetoric, Pathos, and the Law of Love

Is it ethical to use a man’s emotions to persuade him?

In the electric atmosphere of today’s propagandistic politics, that question is charged. By and large, even teenagers expect that the vast majority of the campaigning, advertising, and peer-pressuring they will encounter is based solely on emotion; this is the definition of propaganda, of persuasion that is untrustworthy and manipulative. The haunting assumption that the persuasion directed at them respects neither people nor truth is one reason for teenage cynicism’s ubiquity.

Little wonder, then, that my more thoughtful rhetoric students are rather uncomfortable with the rhetorical appeal to pathos, or emotion. Logos, the appeal to reason, they recognize as foundational to argument; ethos, the appeal to character, they are surprised but interested to find so influential; yet pathos they tend to beware as a concession to human weakness, an indulgent spoonful of sugar to make the argument go down, a slope that slips down to the mire of propaganda. So at times, when I have opened class with that question—Is it ethical to use a man’s emotions to persuade him?—my students have responded at first in the negative.

I could argue with them from human experience, from Aristotle, or from Plato’s trichotomous soul that the use of emotion in persuasion is at least unavoidable, and that it therefore has a sort of ethics of necessity. But instead, I try to divert their thinking with another stumper:

In seeking godliness, is it more important to share God’s knowledge, or to share His emotions?

Of course they all want to take the easy way, the correct way, and say, “Both.” But I push them to consider—even if it is a fallacy—on which side of the either/or they’d stake their claim.

On the one hand, to know and believe and confess the identity of the Trinitarian God seems to be the first, fundamental step in godliness: How then shall they call on Him in whom they have not believed? . . . If you confess with your mouth, Jesus is Lord . . . Whoever confesses that Jesus is the Son of God, God abides in him, and he in God.

And yet, on the other hand, even the demons believe—and shudder . . . and it was the tree of knowledge whose taste brought death into the world, and all our woe. Not those who say, Lord, Lord!, but those who act in love, shall enter into the joy of the kingdom. While knowledge in the mind is needful, the emotions of the heart seem at least as significant.

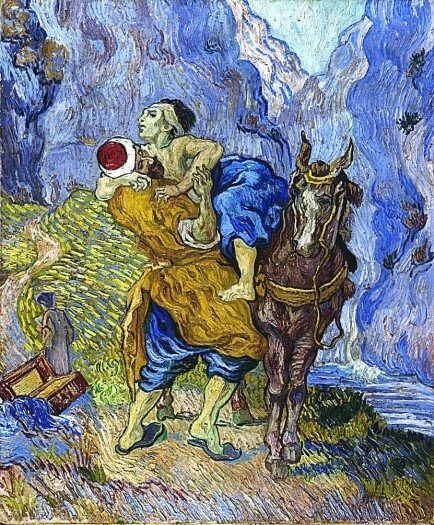

In fact, if godliness is summed up in Christ’s two greatest commandments, to love God and neighbor—what theologians dub the Law of Love—then sharing God’s knowledge is merely prerequisite to imitating His emotions: we must know who God and neighbor are, but the real test comes in our emotional response to them. The old Puritan word expresses it better; they did not speak of emotions, as if the human heart is a wash of passive feeling, but affections, recognizing that all feelings are aroused and directed towards particular objects. Sin twists our affections, causing us to feel delight in wrongdoing, anger at justice, pleasure in disobedience; the sin-bent soul looks like a totaled car, bent beyond use or recognition. The great work of godliness is to realign the heart’s affections so that they run parallel to God’s: anger at sin, grief at suffering, joy in obedience, peace in faith.

So then . . . we begin to come back to the initial question, whether it is ethical for a speaker to use the audience’s emotions to persuade them. If godliness can be described as the realigning of emotions, and if the Christian orator ought always to be encouraging his audience towards greater godliness—then it begins to seem unethical to not address the emotions in persuasion. Rhetoric bound by the Law of Love will place ultimate importance on bringing the audience’s emotions on any subject in alignment with God’s, for their very souls may rest on this. Logos and ethos are essential, for the truth must be known and believed before anything else can occur; but the final goal of persuasion, and of life, is not merely to know the truth, but to love it.

Lindsey Brigham Knott

Lindsey Knott relishes the chance to learn literature, composition, rhetoric, and logic alongside her students at a classical school in her North Florida hometown. She and her husband Alex keep a home filled with books, instruments, and good company.