In Praise of Used Book Stores

Throughout Western history, books have embodied truth and knowledge; thus, the way that books are organized and obtained embodies how knowledge can be organized and obtained.

The most effective way to shape our students’ epistemologies is to take them to used bookstores.

An overstatement, surely—but worth considering. Epistemological formation, or instruction in how we know what we know, must be a central pursuit of Christian education, for Pilate’s question has echoed down through two millennia and the reverberations of the three words “What is truth?” are now louder than Poe’s tintinnabulating bells. The whole history of philosophy anno Domini could be cast as a sustained attempt to answer them.

Now, overwhelmed by the cacophony of voices, many of our contemporaries claim that no single truth is necessary. Yet attempts to enforce absolute truth(s) still occupy our courts, congresses, and schools—evidence that modern people care deeply about the definition of truth, but have no consensus on how to reach it. Thus, all of a Christian education must be bound up in the effort to nurture and explain Christian confidence in the knowability of what Francis Schaeffer dubbed “true Truth.”

Apologetics and worldview training are, of course, an important part of this effort. But as the classical world emphasizes, education does not only or primarily disseminate ideas but also inculcates virtues—not only forms the mind but shapes the person, body and soul. And as James K.A. Smith has recently contended, this means that “we’ll also have to broaden our sense about the ‘spaces’ of education. If education is primarily formation—and more specifically, the formation of our desires—then that means education as formation is happening all over the place (for good and ill).”

Illustrating this, Smith presents an extended “case study” of the way that the physical space and practices (“temple” and “liturgies”) of the American shopping mall form its customers’ desires and religious impulses. He asserts, “If education is about formation, then we need to be attentive to all the formative work that is happening outside the university: in homes and at the mall; in football stadiums and at Fourth of July parades; in worship and at work.”

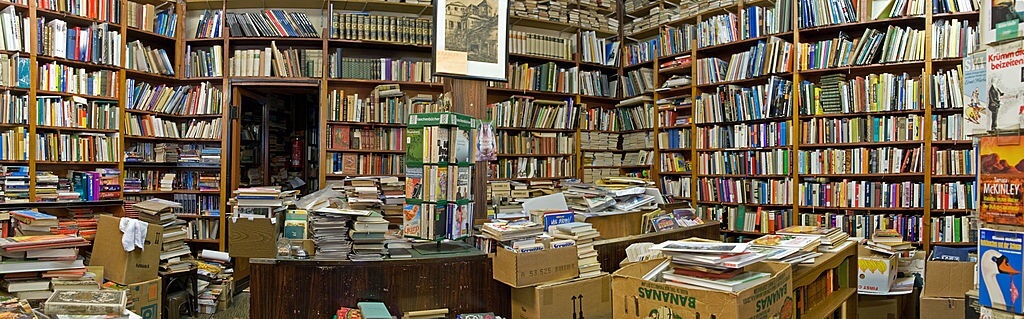

And at bookstores. Throughout Western history, books have embodied truth and knowledge; thus, the way that books are organized and obtained embodies how knowledge can be organized and obtained. Chronological or alphabetical? The former portrays knowledge as being discovered over time; the latter portrays it as systematic and comprehensive. Arranged by author or title? The former highlights the human dimension of discovering knowledge; the latter foregrounds the content of its discovery. Neatly shelved or haphazardly stacked? The former displays the attainment of knowledge as well organized and fairly effortless; the latter reveals it as a somewhat precarious pursuit.

I used to be a Barnes and Noble patron, having one conveniently located ten minutes from my home. But as the books were pushed further and further back in the store to make room for the shelves of chocolate, calendars, board games, and other plainly necessary accoutrements to the task of reading, I became uneasy, and on the day that I entered the bookstore to behold a temple to the Nook erected not five paces from the door, I knew I would need to look to elsewhere to suit my purist bibliophile sensibilities.

Thus began the forays into used bookshops. I discovered with delight their varied personalities: the haphazardly comprehensive shelves at Robert’s Booksellers by the train tracks near my college—”Purveyors of Old and Rare Books, Especially Theology”; the long dark room with books stacked on the floor at the Captain’s Bookshelf discovered during summer travels; and at home, the proper dark wood cabinets at San Marco Books, and the crazy mazes of the Black Sheep bookshop.

More than just a space for consumerist exchange, however, the physical arrangement of these stores both embodies and inculcates many facets of a healthy theory of knowledge. Take, for instance, Chamblin’s, queen of used bookstores in my hometown. To begin with, the floor plan rivals Minos’s labyrinth. I have yet to form a clear mental blueprint of the aisles that run together, turn corners, twist into alcoves and closets, and finally dead-end. Absent a golden thread, there are, at least, signs with arrows guiding the adventurer through the maze. Strategically located signs locate the exit. Many others announce the subject matter of the shelves at hand: Paperback Classics, Hardbound Classics, Biography, Naval History, Southern Biographies, the War of Northern Aggression, Mystery, Sci-Fi, Geography, Poetry, Philosophy, Car Manuals, Gluten-free Cooking, Geographical Cuisine, Southern Cuisine, Lacemaking, Gardening, Southern Gardening, Christian . . . all of these are among the labels placed on or over shelves. Within each section, books might be arranged by title, by author, by location, by time period—or by some combination of these. These shelves, however, are not sufficient. On top of them, between them, at either end of them, more books are stacked. And customers are made aware that a warehouse behind the bookstore houses another few thousand codices.

Perusing both shelves and stacks discloses acquaintances old and new. Many of the books, of course, are either timeworn classics or popular fads. But an equal number are by unknown authors on forgotten subjects. (In my most recent trip I picked up out of the gardening section a volume titled Vegetables of the Garden and the Legends by one Vernon Quinn. It’s a delightful book with a woodcut frontispiece captioned, “The leek had played its part in King Arthur’s victory,” and, as the title promises, it is filled with stories of how common vegetables came to be popular on our dinner tables and the adventures in which they participated along the way. What’s not to love?) And, in addition to the books and their authors, you often make the acquaintance of previous readers. Their names are beautifully inscribed or hastily scribbled on front covers, their notes scratched into margins, their favorite passages marked in all manner of ways.

So how do these spaces press their visitors to conceptualize knowledge? The labyrinthine paths portray it as vast and intriguing. Their curious organization defies the certainty-seeking of Descartes and Diderot that is reflected in the neatly alphabetized shelves common in chain bookstores. Instead, truth is structured as comprehensible but not conquerable. It is not impersonal and ahistorical, but is treasured and passed down by particular people of particular times. Relationships among ideas are fluid and can be expressed in multiple ways. The shape they take reflects the background and personality of the one assembling them (the bookstore I described is obviously an eclectic yet proudly Southern one). Pursuing ideas takes determination, perseverance, and curiosity, and will sometimes yield what you are seeking and other times something you did not know to seek.

A far cry from a text on epistemology, certainly. But these themes, while not directly answering Pilate’s question, nevertheless cultivate habits of mind that contribute to a healthy theory of knowledge, one prepared to seek and receive truth. A Christian epistemology will aim for confidence, not certainty; it will value both the universal content of knowledge and the particular people who pass it on, not letting one dimension override the others; it will be open to wonder.

And so—not to overstate the matter—the most effective way to shape our students’ epistemologies might be to take them to used bookstores.

Lindsey Brigham Knott

Lindsey Knott relishes the chance to learn literature, composition, rhetoric, and logic alongside her students at a classical school in her North Florida hometown. She and her husband Alex keep a home filled with books, instruments, and good company.