What To Say When Your Students Fall In Love

I. A student once asked me if I thought it was okay for high schoolers to fall in love. I replied, “As long as the love isn’t requited and the student tells no one about it, I don’t see a problem with a high schooler falling in love.” I may have added some other caveat about the love slowly tearing the lover apart on the inside. I was only half-joking.

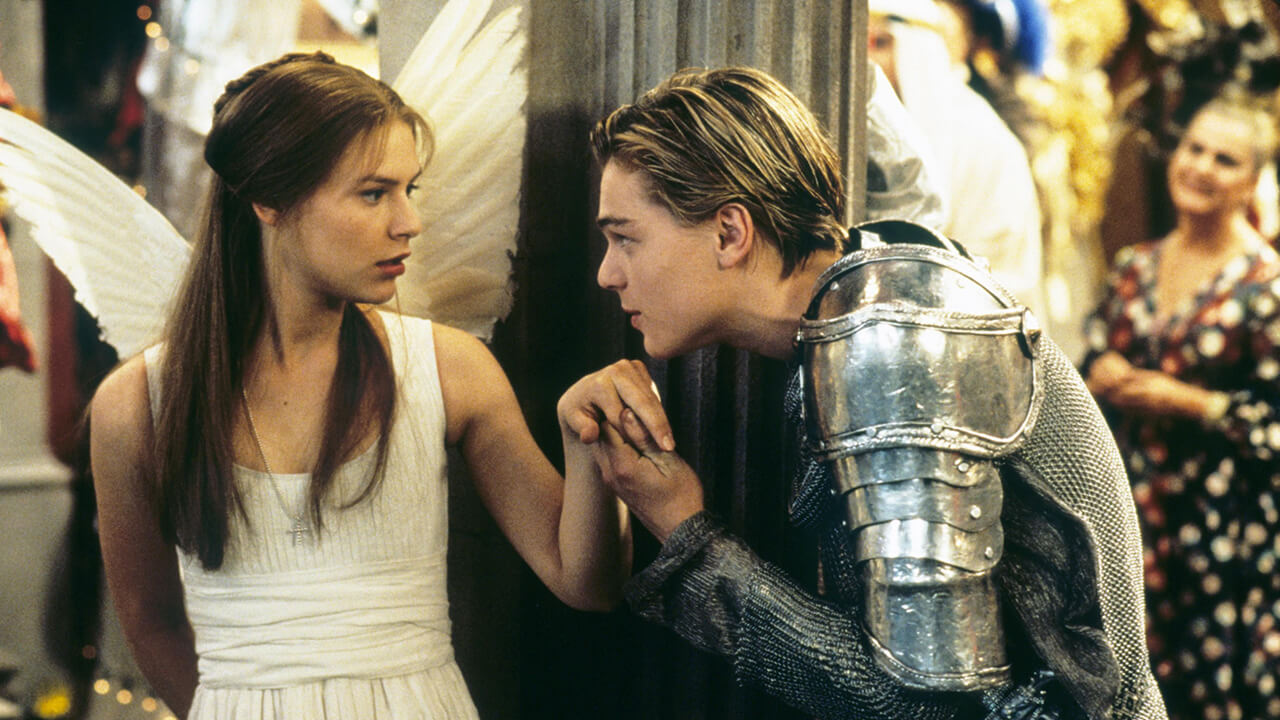

When I was sixteen, I had brash taste. I listened to nu metal and wore Fubu jeans. A yearlong crush I developed for the demure, thoughtful Agent Dana Scully from The X-Files in my sophomore year cured me of that. A crush I had on a quiet, introspective girl at school my junior year was also helpful in delivering me from the absurdities of bad teenage style. The girl in question was bookish, contemplative and lived in a rumpled, comfortable home, and her parents were both academics. Seven years after I graduated, we married.

While we were both in school, I worshipped her from afar, which is to say I cobbled together what little I knew of her and fashioned it into a character which was at once real and fictional. I did not love her, because love is service and sacrifice, though I struggled to remake myself into the kind of person she might love. I wanted to read books. I wanted to be quiet. I wanted to be content by myself. I was confessedly unworthy of her, but I wanted to be worthy, so I began rounding off the harsher edges of my personality to suit her, though she knew of none of this. Having been married to her now for nearly eleven years, I can say that the fictional image of her which I crafted back in high school was both exactly like and exactly unlike the woman she proved to be.

II. Have you ever had a crush on a fictional person?

In an informal poll I conducted last year, an entire class of Modern literature students claimed they had. The question was and was not a trick. In truth, a crush is always a fictional person. While “crush” is a neologism and not a philosophically vetted term, the crush represents one of the most significant concepts within Western morality in the last thousand years. While not a term traded by the courtly love theorists of 12th century France, Andreas Cappelanus’ 1186 AD text De Amore seems to speak of the crush. Here’s a few choice bits from the middle of his 31 item rule:

13. When made public, love rarely endures.

14. The easy attainment of love makes it of little value; the difficulty of attainment makes it prized.

16. When a lover suddenly catches sight of his beloved, his heart palpitates.

17. A new love puts to flight an old one.

18. Good character alone makes any man worthy of love.

19. If love diminishes, it quickly fails and rarely survives.

20. A man in love is always apprehensive.

24. Every act of a lover ends in the thought of the beloved.

25. A true lover considers nothing good except what he thinks will please his beloved.

It is true enough that love is not mere feeling, but sacrifice. It is true enough that love has been corrupted by the cult of courtly love, by romance. Just the same, the deepest love does not make sense without a little of the crush.

For anyone familiar with Dante’s La Vita Nuova, or with Peter Leithart’s Ascent to Love, the crush is not a difficult concept to grasp. Granted, the term “crush” smacks of trite, vapid, shopping mall conversations between teenage girls, and it may be that there exists a term more venerable than “crush” for the phenomena which I want to discuss, but I have not encountered it. If the reader’s sense of dignity is insulted by a lofty treatment of the crush, he is free to depart in peace now for the fairer climes of a Bonhoeffer treatise on Eucharistic community. For those who remain: the universal patterns of human intellectual development are their own kind of sacred text, and despite the difficulty with which the adult listens to the pained, batholithic confessions of the adolescent, yet the experience of adolescence is no less holy than the experience of maturity.

The crush is the imaginative work which precedes love. The crush is not service of the beloved, but a reimagining of the world as a place fitting for the lover and the beloved. The crush is a Herculean intellectual labor in which the whole cosmos is reinterpreted in a manner the beloved will find compelling. The crush is the reimagination of the self as a new man, worthy of the beloved. The crush is a struggle for the virtue needed to please the virtuous beloved. The crush is not love, and often fails to become love, but must always preface love when love is to become real. Despite the banal luggage which attends the term, it is nothing less than the logic of the crush which prompts the creation of Eve, and it is the same hidden logic of the crush which calls forth St. John the Baptist’s maxim which liberates man from the bondage of the self, “He must increase, but I must decrease.”

To crush is to imagine “the beloved” is present when they are not. To crush is to attempt to please the beloved in all things. A man swings his legs out of bed in the morning in a way the beloved will find pleasing. A man speaks, enunciates, remains silent in a way he thinks the beloved would find pleasing. To crush is to behave as though a man has a worthy, discerning audience in all he does. The crush begins love because the crush has not yet earned the right to live near the beloved. The crush understands that love is an imaginative, creative project where souls hang in the balance; little hangs in the balance of the crush, though, because the crush is unproven and possesses no physical power or responsibility.

The beloved sits upon the shoulder of the man with a crush, judging all he says and does; the man who gives little thought to himself and the man who cannot see himself as a character in a story would do well to have a crush. The man with a crush thinks of the beloved in a way which offers no immediate material, sensual benefit to himself. The man who artfully swings his legs over the bed in the morning benefits nothing in doing so except the beauty of form. The crush is practice for the difficult work of love. Love is obedience, sacrifice, though a man should learn to practice obedience and sacrifice before he must obey and sacrifice. A man may practice such obedience and sacrifice in piety, in faithful obedience to God, but a man should also refine his manners and taste to please another human being. Adam need only satisfy God, while the overflowing gratuity of Eve’s being satisfied Adam and God. The animals were a gift to Adam, and God made them for Adam in much the same way a man buys flowers before taking a woman out to dinner, not while he is taking her out. That God leads the animals to Adam “to see what he would call them” suggests God made the animals with Adam in mind. Prior to his creation, Adam sat on the shoulder of God’s imagination.

While Beatrice was an historical figure, the Beatrice whom Dante had a crush on was an eschatological vision. She was real in the sense that the final cause of a thing is also the true nature of that thing. The Beatrice of Dante’s imagination was both authentic and speculative. The man with a crush does well to make himself worthy of the most worthy of women; in reimagining a woman in all her eschatological glory, the dreamer with a crush calls himself to a far higher standard than the so-called realist. The clarity of Dante’s moral vision was born not only out of study, but his ability to live in solitude as though in the presence of another. Morality is not possible without fictionalizing the Other. Without the fictional Beatrice, Dante has no mature moral vision because he has nothing to live himself up to.

One of very few happy stories in Greek or Roman mythology is that of Pygmalion and Galatea, the fictional stone person whom the goddess of love makes flesh and blood. Ovid does not pathologize Pygmalion by arbitrarily repaying his artistry with divine jealousy, but presents the sculptor as a quiet, responsible artist whose solitude fires his imagination with a yearning so divine, Pygmalion thinks it inhuman to pursue. Ashamed to pray honestly, Pygmalion merely wishes for a woman in the likeness of his beloved character, but Aphrodite grants him “infinitely more than he can ask or think.” The gods are still sometimes given to such generosity. The man who begins to love with the goddess on his shoulder often receives a goddess at his side.

III. One of the profound secrets of courtly love is the arbitrary nature of the beloved. It matters little if the beloved is virtuous. The lover involves himself with the divine work of “looking the world back into grace” as Robert Farrar Capon once put it. Whether the beloved is as wondrous as Beatrice or as shrew-like as Katherine the Curst, the imagination of the lover purges all imperfections and speaks “a world of words” for the beloved to step into (the phrase is borrowed from Leithart). Bearing witness to a perfected beloved, the lover begins moving toward her and thus rises through the cosmos, nearer and nearer to the God who grants such perfection.

Every school ought to have sufficient policies in place to keep students from holding hands as they walk from class to class, and the earliest and most important rule of love is self-control. In this way, I suppose telling students who suffer the pangs of love to simply quash such feelings is one way of going about it. I am all in favor of banning public displays of affection, and the administration which forthrightly discourages all romantic relationships acts in wisdom and prudence. It should also be noted that the ability to quash romantic feelings will be of increasing value to a man the older he gets; the married man who develops feelings for his secretary will simply have to throw those feelings down a black hole.

That said, there are other ways of addressing the student in love.

For many students, the idea that a secret affection for another should prompt a zealous pursuit of excellence will be intuitive— they already know it. Others will need the idea presented and explained to them. I should be clear that when I talk about the ennobling power of a crush, I am not speaking of some agreeable fantasy of the future. Daydreaming about the pleasantries of a marriage to so-and-so are petty distractions. What I am suggesting, though, is that the courtly love tradition (especially as Dante adjusts it, refines it) commends the power of the crush be put to good use, not simply drained and discarded. We love what is good, and the only way of drawing near to what is good is by becoming good.

There are ways for a school to ban student romances which will only make it harder for students to enjoy good romances later on. To speak as though romantic feelings must always be quashed is to treat love like lust, to stigmatize love, and to needlessly oversexualize romance. Further, telling students not to pursue romance in high school merely because romance is distracting from study is not simply naïve, it creates false expectations about marriage. As Eugene Rosenstock-Huessy notes in The Christian Future, all modern men are constantly torn between work-life and home-life, and the obligations of one sphere are always tearing a man away from the other. Work matters regularly distract me from my wife, my wife regularly pulls me from work I need to do, and man is born into trouble as flames rise.

On occasion, I have also heard adults counsel students away from romance because romantic yearnings “cannot be fulfilled” while so young. If this means that there is no use in falling in love until a lawful and righteous sexual relationship is possible, the advice is very bad. A man who is raised in a culture wherein sexuality is omnipresent should not have it suggested that, once married, all of his unfulfilled sexual desire will be laid to rest. For many, marriage will mean the subsiding of some—but not all— right romantic yearnings. On the other hand, if the idea that young romantic inclinations “cannot be fulfilled” refers to the psychic vexations which attend unrequited love, then advising the young to avoid romance is even worse. Christianity is a religion which regularly commends such vexations— the “unapproachable light” in which God dwells, the unknowable nature of the divine, seeing now “through a glass darkly,” living in a time “before the perfect has come,” living as sojourners and aliens who have not found a permanent home, St. Paul’s dictum that “we are perplexed.” The Christian life is not entirely bereft of spiritual agitations, and to speak as though every irritation of the mind and soul should be avoided is to render Gethsemene an unfortunate, needless hassle.

All that I have written here might be on the line when a teacher is individually counseling a single student, although my thoughts are really more directed toward the way philosophy and theology and literature teachers advise students on the nature of romance from behind the lectern. Without vindicating any and every romantic sentiment ever felt by a sixteen year old boy, let us at least say that romantic feelings among the very young are not always sinful, which means that sometimes they are gifts of God. As such, they cannot be buried in the ground, but must be spun out into even greater gifts. To this end, Dante offers the young man and woman something which is at once strange and yet, I believe, uniquely satisfying.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.