When Your School Begins To Die

Institutional Christianity in America is in for some dark days. I will take this as a truth which needs little defense. How does a classical school prepare for such days? And how does the suspicion such days are at hand change the way we conduct ourselves today?

There was a time when wealthy families prided themselves in committing a son to a monastery. Several nights ago, I heard a priest read a story from the early Medieval era wherein a city was described as having more than five thousand monks. The longer one reads history and contemplates the mysterious movement of one epoch to the next, the more astounding the monk becomes: unlike a laborer, he works for free, and unlike a slave, he is educated. Throughout the Medieval era and into the Renaissance, the monastery was something like a battery which provided endless energy, never needed recharging, and never ran out. The monastery was a cultural storehouse which amassed during the fat years of Christendom, and has been drawn from steadily since the end of Christendom.

Seasons of fatness and leanness perpetually alternate. Such seasons might be personal and individual, but they are also experienced by families, cities, states, creeds, denominations, and nations. Fortuna is always turning her wheel, and lest any man (or nation) become too complacent with their fatness, or too despondent in their leanness, something new and other is ever on the horizon. Solomon writes, In the day of prosperity be joyful, and in the day of adversity consider: God has made the one as well as the other, so that man may not find out anything that will be after him. In Genesis, God teaches prudence and chastity during the fat years by way of a promise that lean years are coming.

Perhaps your school has done well for itself over the last few years. Or, perhaps your numbers are diminishing, and slumping numbers have led to slumping spirits. The point at which the fat days begin turning lean is always ripe for self-reflection. Who am I really? Who are we really? What changes are we permitted to make— what adjustments in our charter, creed, or vision are malleable— in order to keep the doors open? Did years of success give us an inflated sense of our accomplishments? Did we claim our success as “God’s blessing” when it was really nothing more than a lucky turn of the schooling market we were capitalizing on?

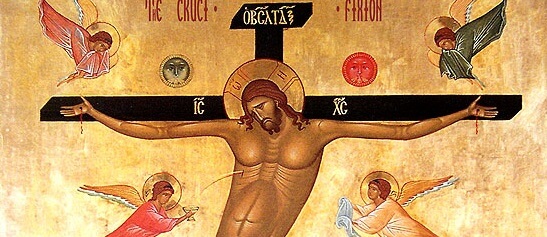

If your school is yet in its fat years, consider this: when the numbers begin diminishing, and when the donations and grants stop coming in, you are not failing. You are being consumed. When the numbers fail, you are not dying, you are feeding people. The thick enrollment, the salary raises for teachers, the perks, the trips, the successful ad campaigns, the years in the black… it all might best be viewed as a season of fatness, and you are the fatness, and eventually that fatness will become food for the starving. You are the cultural capital of Christianity, a cultural savings account which can be drawn from when it all goes belly up. As you are eaten, you are sustaining Christian culture for a day longer. Every year enrollment goes down 5%, someone’s spirit is quickened at your loss. In The Divine Comedy, Dante refers to Christ as “our Pelican” because, in times of extreme want, a pelican will use its own beak to pierce its chest and feed its own blood to its young. The cruciform life of a school requires such sacrifice, although you will not see the young you are feeding. The Christian vision stays afloat today only because it was so high above sea level last year.

However, it all feels very different. It feels like failure, like judgment. It is not failure, however, it may be judgment. It is crucifixion. It is the breaking of bread for hungry bodies.

The prudence which the coming lean years can teach us today, in our relative fatness, is not necessarily fiscal prudence, but prudence of spirit. In his commentary on Ecclesiastes, Martin Luther describes the need to “make space” in our hearts for grief before grief arrives; when grief arrives, we need to know where to put it, rather than scrambling around, clearing out boxes and tables and haphazardly moving the furniture closer together. If the lean years have come for you, or if they came a long time ago and you have been all eaten up— and if your dream and your school died an emaciated death somewhere in the flyover states or the lonely West— accept the thanks of someone who is alive today because of you.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.