What Does Goodness Think Of You?

On the opinions of students (and teachers)

I recently read a former Duke Divinity student say that, in his time at the school, Stanley Hauerwas would regularly walk into a classroom and tell his students that none of them knew enough to have an opinion, and that he was going to teach them instead. Say what you will about Hauerwas’ bedside manner, the story rang true. In my nine years of teaching literature, some of the least profitable discussions I’ve lead have been born out of that great meaningless question which young teachers are particularly prone to: “What do you all think of that?”

The question has a few different incarnations. If the class is moving slowly through a book, reading a few paragraphs and then stopping to discuss, young teachers will often poll the class for “any thoughts.” Or a teacher might assign a chapter for homework and open up class the following day with, “Any thoughts on the reading from last night?”

Up front, I should say the question is not always inappropriate, and that it can be employed in particular circumstances to great success. However, the question is opposed to the spirit of classical education. It does not matter what the students think of the text. Contra Hauerwas, it doesn’t even matter what the teacher thinks of the text. The teacher is simply the person with the greatest appreciation of how little his opinion matters.

When I don’t know what to say about a text, or I don’t really have a firm grasp on the argument or the narrative, asking “What do you all think of that?” is a convenient way of removing the responsibility to teach from myself and foisting it on the students. I don’t have a perfect understanding of everything I teach, and when I come to a particularly knotty passage in God in the Dock, asking the students to say something interesting about it relieves me of having to say something interesting, because I can’t or because I’m being lazy. There is an air of generosity to the question, though. It is expansive, libertine. The student may take off in any direction they please and not betray the question.

The question is not truly generous, though. “What do you all think of that?” is a question without limit, without direction, without particular interest. Having taught poetry electives for years, I can well attest that the worst student poems are generally written unto the prompt, “Just write a poem. Whatever you want.” The best student work is born out of satisfying prompts which require this many lines, this many Biblical allusions, so many poetic devices, or that students craft a likeness of this Larkin poem or that Frost poem. “What do you all think of that?” is merely a request that someone talk, someone say something to fill the silence.

The most common answer to the question is a shapeless answer expressing personal conviction or taste. “I liked it. I thought it was good,” or “He makes the case too strongly. I think he should have been a bit more mild.” The question often calls forth judgment, wherein the student decides if the text or the idea is up to snuff, or if it comports with the student’s preformed prejudices. The teacher who generically asks his students what they think puts his students in a position of priority over the text, where the text stands or falls based on what the student already believes. Granted, this isn’t always what happens, but the student is usually being robbed of the ability to think through the text deeply, carefully. The student is hustled along to the conclusion of the matter without being shown what they need to look at, what they need to think about. The question takes the focus off the book and puts the spotlight on the teacher and the students. It should come as no surprise that theologians and philosophers of our day cannot speak of great ideas without speaking of themselves, however, you never find one of St. John Chrysostom’s sermons begin, “I had a few interesting ideas occur to me the other day while I was reading Genesis…”

Ours is the world of the endless river of nearly-worthless songs and books and photos and games and videos, and we are ever offered the opportunity to express like or dislike for each insignificant trifle which comes near us. Is this not profoundly taxing? Does it not sometimes seem a catastrophic waste of time to so minutely catalog our tastes, given how exceedingly ephemeral our culture is? However, a classical education stages an encounter between the student and Goodness, not so Goodness may be judged, but so the student may be judged by Goodness. It is in Orual’s silence that the Judge asks her, “Are you answered?” And indeed she is, or she is beginning to be answered.

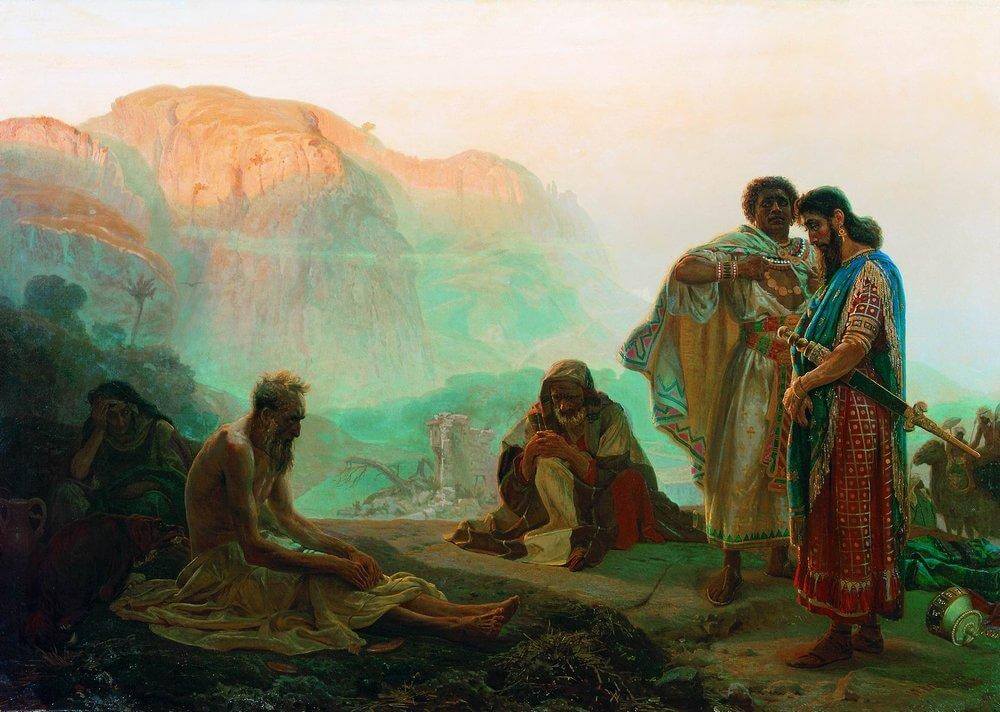

A classical education is chiefly concerned with humility. Not the humility of an athlete pointing to the sky in a moment of glory. A classical education is the humility of Job passing through a fire. The humility of Job in exile, sitting atop a pile of garbage outside of town, demanding to speak with God face to face. The humility of Job, incredulous of the easy answers his wicked friends offered to his outrageous, unanswerable questions. A classical education lays bare the ego of the student and leads the student to the same pile of garbage upon which Job sat. A classical education teaches the student to pantomime Job’s fury and sadness until the performance becomes real. Then, and only then, God will come to the student and the student will cover his own mouth and God will reveal great mysteries to the student, as He did Job. A classical education teaches the student to imitate Job’s joy at the reunion with his dead children until the joy becomes authentic. A classical education teaches the student to mimic Job offering sacrifices for his wicked friends, and in this the student is reconciled to the world. Imitation is a kind of silence. A monk praying the Psalms of David is practicing silence inasmuch as He resists his own words in favor of God’s words. The man who fasts as Moses, sings as Miriam, weeps as Jeremiah, and gives as Francis of Assisi is practicing the silence of Job.

As opposed to asking, “What did all of you think of that?” I have nothing particularly novel to suggest. If students read “My Papa’s Waltz,” by Theodore Roethke, the teacher will be far better served by asking, “Is this poem actually about dancing? If not, on what level does it seem to be about dancing? What words give the impression the subject is actually not a dance?” It might be argued that these questions call for the opinion of the student no less than “What do you think of the poem?” However, “Is this poem actually about dancing?” is a question wherein the teacher takes responsibility for helping the students to shape their thoughts. In the same way, the husband who asks his wife, “Is something wrong?” often really needs to say, “I apologize for being late to dinner last night,” and not coerce the wronged person into the uncomfortable position of making an accusation.

The teacher who understands the insignificance of his own thoughts is best suited to lead his students into genuine wonder; if the lit-teaching Mr. Smith doesn’t recognize his own opinion is less important than the opinion of Mr. Rousseau or Mr. Burke, he is probably not an interesting enough person to listen to anyway.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.