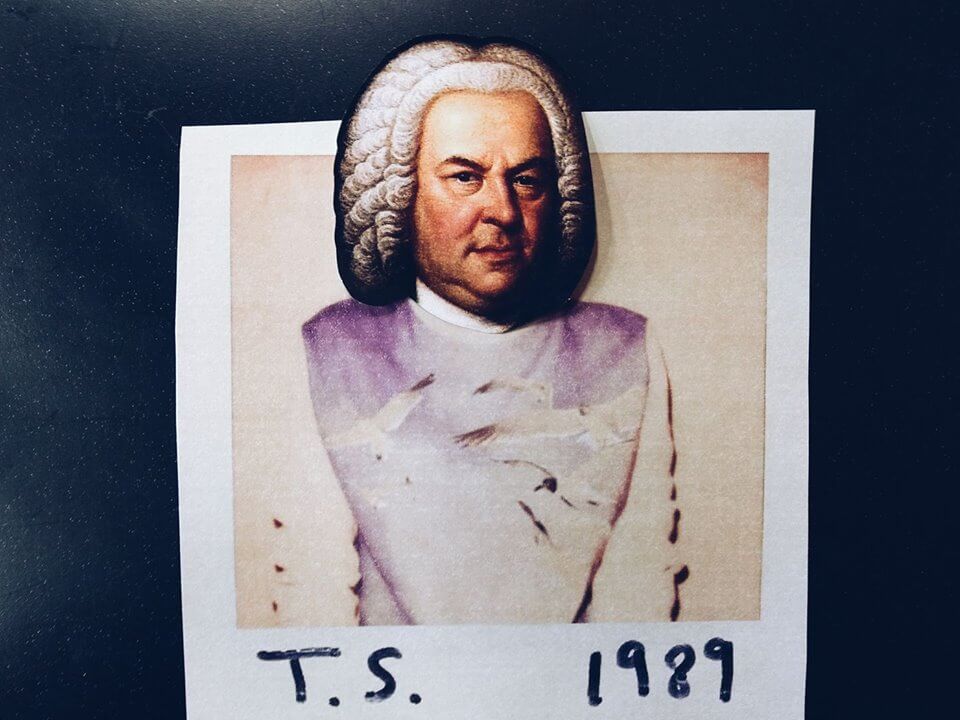

Was Bach Making Pop Music Back In His Day?

While I maintain a massive library of 20th century music, and a modest library of 20th century films, when I stand behind a lectern, I generally advocate for old things. New things are rather easy for us to enjoy, for they are made for us and by us and “no man ever hated his own body.” But old things are much harder to like because they are made by strangers. The past is another country, and we are always struggling to learn the language. New things dominate the world outside the classroom, and our culture is content to castigate old things merely because they are old. Suffice to say, our students will never be in want of new things, but they will often be in want of old things. However, the classroom is a place where old things are not simply safe, but given preferential treatment. If the school does not advocate for old things, there is simply no other institution in existence today which can be depended upon to do so.

From time to time, though, I field objections from students who tire of the classical prejudice in favor of old things. I speak dismissively of the current incarnation of Britney Spears and someone smartly replies, “Bach was pop music back in his own day.” Or else it is claimed Euripides was the JJ Abrams of his day, or John Milton was the Rick Riordan of his day. In some sense, the point is a fair one, for Christ’s teaching that “A prophet is not without honor except in his own country” is a pithy way of suggesting there is something a little embarrassing about most origin stories. Why is the prophet without honor in his own country? Because the folks from back home remember when his voice was cracking at the age of twelve and now the fellow claims to speak on behalf of God Himself. The notion that Bach was pop music back in his own day is often given to win greater credibility for the pop culture of our day. Just because something is not old doesn’t mean it’s not good. There was a time when Bach was brand spanking new.

That said, the idea that Bach was pop music back in his day, or that Shakespeare was the Spielberg of his day, is a claim in need of some investigation. While some might object that “Shakespeare was pop culture in his own day” involves an equivocation of “pop culture,” I have no problem going along with the claim that the average attendee of Much Ado back in 17th century England bore a striking similarity to the average attendee of Bad Moms today, say.

The idea that Shakespeare was nothing more than pop culture in his own day does not equivocate on the term “pop culture,” but it does equivocate the word “Shakespeare.” Shakespeare may have been pop culture in his day, but he wasn’t entirely Shakespeare. This claim is not simply an essential classical prejudice, it also sits near the very heart of conservative political theory (I should note before going further that when I refer to conservative political theory, I am not really referencing anything in the contemporary American political landscape. Rather, when I refer to conservative political theory, I am primarily referring to the work and thought of Edmund Burke. For Burke, man was the traditional creature— man was the creature who received from his parents what he passed on to his children. Those he stood against conceived of man as the willing creature; to be human was to want. The extent to which any political party in America wants anything to do with Burke or Rousseau, however, has always been an unresolved question in my mind).

Both classicism and Burke’s conservatism presuppose very particular beliefs about time. While progressives hold that man is fundamentally oriented toward the future, conservatives and classicists believe he is oriented toward the past. Progressives hold that a man’s progress into the future is much like a man walking forward through a field, though conservatives believe man is walking backward through a field. The progressive believes a man may choose what future he would like and simply move toward it (a man choose to walk to a mountain several miles ahead), while the conservative holds that the future is uncertain, unpredictable. Consequently, the progressive believes that every event of the past is slowly become more obscure and increasingly irrelevant. The conservative believes that the great events of the past cannot be known at all until they are far away. To tease out the metaphor, the man who moves through the world backward does not know that he is about to cross a mountain, neither does he know how high the mountain goes or where it ends, until he is some ways away from it. The conservative is generally confident that close proximity distorts, while the progressive believes it makes clear.

If we imagine a man moving through the world backward, ignorant of the future but ever more clearly bearing witness to the past, there is a sense in which books of the past do not change, and a sense in which they change quite a lot. The Divine Comedy both was and was not The Divine Comedy back in 1321. It was The Divine Comedy only in the sense that the same arrangement of words on the page which any Italian might have read 700 years ago are preserved intact to this day. However, The Divine Comedy could not be known as anything other than a hill when it was first released, though we know it as a mountain today.

The classical prejudice assumes different kinds of things respond differently to time: pasteurized 2% milk in the back of your fridge spoils after 60 days, but there is a way of treating the same milk such that it becomes camembert. Treated one way, grape juice tastes like purple popsicles, treated another way it tastes like bronze and stones and plums. Time destroys earthly things, but divine things absorb time and transform time from a corrupting power into a sanctifying power. Time can either transform a bad memory into bitterness, or time may tame a bad memory into something worth laughing about. To deny the transformative power of time is deny the spiritual aspect of a great book, a great piece of music, a great piece of cheese. In The Portrait, Gogol describes the power of the artist to create spirit as such:

It was plainly visible how the artist, having imbibed it all from the external world, had first stored it in his mind, and then drawn it thence, as from a spiritual source, into one harmonious, triumphant song. And it was evident, even to the uninitiated, how vast a gulf there was fixed between creation and a mere copy from nature.

The “mere copy from nature” is the stagnant object, the material, the talent a man buries in the ground. But the man who loves the world draws the world into himself (the paint, the milk, the line, the word), breathes spirit into the raw material, and then returns nature to God beatified, transfigured.

This is something of a side issue from where I began, which was with the question of whether Bach was pop music in his day, though I will return to my first thoughts with this claim: if Bach was always only Bach and the Goldberg Variations have always only been the Goldberg Variations, man’s power to create is not even a fitting tribute to God’s power to create. If art does not mature over time, and if the artist is only capable of reorganizing nature into a solid, monolithic object, then civilization is little more than a big game of king of the hill.

I much prefer to think of art in terms of St. Paul’s conversion, though. While the event itself remains unchanged, the Apostle’s power of perception strengthens over time, and the further from his encounter with Christ he gets, the more clearly he understands it. When Paul first recounts his conversion, he describes the light of God as “a great light,” and yet when he later testifies before Agrippa, he understands the light of God as, “a light from heaven, above the brightness of the sun.” While the Damascus road encounter remains a static event from history, time has enriched Paul’s mind and his memory. Inasmuch as we encounter Truth, Beauty, and Goodness in Bach or Shakespeare, we also meet God on the road to Damascus… and the further we move from Bach, the more clearly we can see him. He is far more than we could have known him in his own day.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.