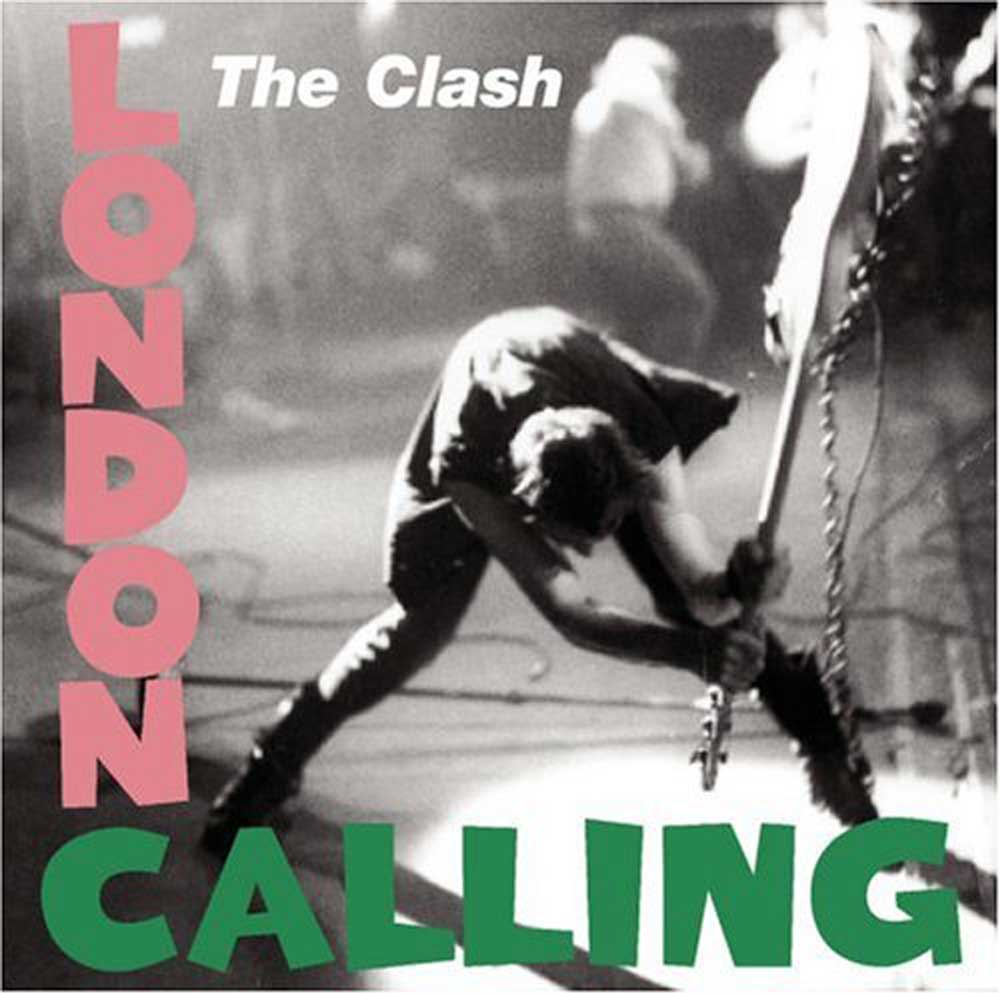

Punks.

I. On Sunday afternoon, I drink a French press and put on Bill Evans or Django Reinhardt while meandering through the forest-clearing, four pound Sunday edition of the New York Times. On the sofa, my wife and I read the paper while our children take a nap, which is an hour if we’re lucky. So far as rest goes, there are few things I value more. When everything about the afternoon falls perfectly into place, I suppose I might submit the moment to the power of an eternal present and simply exist forever inside of it.

At the same time, if you’ve not recently perused the New York Times, it’s about as harrowing to a man’s hope in humanity as anything has the right to be. Finish the Styles section and the Review and you’ll be apt to wonder if the concept of transgression has any purchasing power at all anymore; every arbitrary spasm of desire has become worthy of veneration. While I recognize that it is the lot of every newly christened adult generation to shake their heads and soberly complain about “kids these days,” I will admit to having suspicions the Western world is in worse shape today than it has been since, say, the fall of Alexandria to the first Caliphate back in the 7th century.

Obviously, even a just society will suffer from crime and that modest degree of impiety the best constitutions begrudgingly allow in the name of liberty (or just a tolerable anarchy, as per Burke). On the other hand, a just society will bemoan theft and rape and blasphemy, and while reports of such vice ought to chill citizens just a little, a cheering warmth might be enjoyed knowing the government, not to mention the most distinguished intellects, yet punish or castigate such behavior. No such cheer comes to roost in the heart of a New York Times reader. A man who lives in a just society sporadically beset by great evil (crime, natural disaster) might turn for aesthetic, spiritual and sentimental consolation to something lachrymose like Faure’s Requiem or Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life or Jeremiah’s Lamentations, any of which might offer an appropriately somber, solemn ceremony of feeling through which to sympathetically enter the pain of others.

However, living as we do, in a society which calls good evil and evil good, the New York Times does not so much sadden me as it does anger and terrify me, and in the last year or more, I have sometimes found myself turning to clawing, abrasive music for solace. I mean the kind of screaming, screeching outrage typical of young, self-professed nihilists.

II. When The Consolation of Philosophy opens, Boethius is imprisoned for a crime he did not commit and awaits execution. He listens to sad songs, pities himself, but when Lady Philosophy arrives, she dispels the muses and quickly diagnoses the philosopher with amnesia. “He has forgotten for a while who he is…” she says, and then begins the long process of helping him remember— not who Boethius is, but what a human being is.

Oddly enough, she begins her consolation like a good atheist. No talk of God. No real protest of evil. Instead of getting Boethius to remember who he is, she first tries to make him forget his pain.

Before getting into the thick of The Consolation, I recently asked a class of sophomores and juniors what manner of consolation atheists might offer a bereaved husband at a funeral. More than a few are often employed by Christians, as well.

“She lived a good life.”

“You’ll always have very fine memories of her.”

“We all have to go sometime.”

“I know what you’re going through. I lost my wife, too.”

“She left behind a great legacy.”

“You can always marry again.” You laugh, but I heard it said once, at the funeral, by the father-in-law of the widower, and from the pulpit, no less.

“You still have your health. You still have your children. Count your blessings.”

While any of these claims might momentarily dull the pain of loss, none of them invoke a hope in God or a hatred for death, God’s enemy. Any good Hellenist, pantheist or atheist might maintain logical and philosophical fidelity to their most sacred beliefs whilst uttering any of them. “Count your blessings” has an air of piety, given that it seems to invoke the spirit of St. Paul’s “rejoice always,” however the two statements could hardly be farther apart. Counting your blessings is a fine thing to do, but it’s not exactly an appropriate response to suffering.

Chances are good that if you count your blessings, you’ll forget about your suffering, and the typical response of Scripture’s heroes to suffering is crying, complaining, and repenting, although Job is arguably exempt from even that last item. The citizens of Nineveh fast and wear cilices so they might remember their suffering. Americans, on the other hand, generally regard suffering as a malignant disease best treated with numbing medication. Our pure of heart are doing “better than they deserve,” when asked, and I’ve more than once been happily told “He is risen” on Good Friday. It is a great mercy no modern day American was around to discover the spot of ground from whence the blood of Abel cried for centuries. We’d have stopped the mouth of that ingrate post haste.

The problem with “She lived a good life” and “You still have your health” is not that they are false claims. The problem is that they are true, and yet they have nothing to do with why the suffering person is suffering. A widower does not mourn because his wife lived a bad life, but because she is dead. A widower does not mourn because he has lost his own health, but because his wife is dead and death is cosmic scandal. Christ wept over the death of Lazarus moments before He raised him from the dead. It does just as much good to recite for a widower the American state capitals as it does to tell him his wife lived a long, full life.

Lady Philosophy begins her consolation telling Boethius that he still has his health, that he still has the memory of the fine day his sons became Roman senators. She tells him he could not take his good reputation with him, anyhow, and that the echo of every good reputation ultimately fades. To his credit, none of these claims is satisfying to Boethius. While less pronounced than in the Scriptural story, the careful reader of the Consolation will begin to see the exasperation of Job in Boethius. The brilliance of the book of Job is the revelation of a man bereft of anything earthly which might give him peace. He had survived the calamity which overtook his whole kingdom, and yet not even his own survival could soothe. We can imagine him borrowing from Juliet to address his endlessly wordy friends. “Be not so long to speak. I long to die.” Boethius holds his complaint out until the end, protesting evil and injustice. As with Job, God arrives at the end of the Consolation, at least in conversation. The final chapters of the book are an elegant metaphysical treatise by Lady Philosophy on how God sees evil as it occurs, but not before it occurs, because “before” and “after” are meaningless terms when speaking of God’s infinitude. God resides in an eternal present, and so God’s knowledge and created reality are always co-emergent. In this way, God is not chronologically prior to creation, as though God came first and stuff came second. God’s priority to creation is the eminence of His being. In this way, God is not the cause of evil, nor does He decree evil; God protests evil just as Boethius protests evil.

Is any of this actually consoling to Boethius? Hard to say, given that Lady Philosophy gets the last word (actually, the last several thousand words) and the final sentiments Boethius expresses prior to her concluding speech are ones of confusion. In the last lines of the book, though, she says, “Hope is not placed in God in vain and prayers are not made in vain… lift up your mind to the right kind of hope…” The sentiment is appropriately Augustinian, appropriately Pauline, for Paul does not teach that we mourn “but not as those who have no good memories.” Rather, we mourn, but not “as those who have no hope.”

III. Like most students of classic literature, I both love and hate the paganism of antiquity. What I love about paganism is perhaps a matter for a different article, but if there is anything certainly loathsome about paganism, it is the sad, barely reluctant capitulation to the fallen contours of city life. There were no pagan punks. A few notable philosophers excepted, they all stood with the establishment, in fear of the establishment. It is a little telling that Socrates, the pagan most often compared with Jesus Christ, was put to death for opposing the ideologies of the state. In his lectures on ancient Greek culture at Yale, Donald Kagan describes philosophers as a great embarrassment to pagan governments. To become a philosopher was to abandon the goods offered by the polis, to take up a life of asceticism, and to seek god on your own and not by way of the priestly cults— all of which betrayed a great dissatisfaction with the civic vision of happiness offered by the local gods. Of course, the role of philosopher seems largely anesthetized by the time St. Paul is walking around Mars Hill, but there was a time…

In “Revolution From Above and Below: European Politics from the French Revolution to the First World War,” the remarkable opening chapter of The Oxford History of Modern Europe, CBE John Roberts suggests that at some point in the 19th century, the word “revolution” became standardized and idealized, capable of meaning in and of itself, apart from any historical particularity. Prior to the French Revolution, one might speak of The Peasant’s Revolt of 1381 or the Morisco Revolt of 1568 in Spain, but use of the word in the abstract was meaningless. A “revolution” has since became an unqualified good. “Jamie Oliver is starting a healthy cooking revolution!” That’s an easily accessible claim today, and one that any giddy domestic might make before chastely heading off to the kitchen to do likewise. However, if Jamie Oliver claimed he was starting “a healthy cooking regicide,” we would look askance, baffled, even while revolution and regicide went together like salt and pepper before 1789.

While “revolutionary” things have become innocuous things, anything “anti-authoritarian” still jingles our bells. That’s leftist. That’s atheist. Perhaps our religious wires have become crossed with our political wires, though. In Atheist Delusions, David Bentley Hart describes the baptism ceremonies of the 2nd century as a kind of wholesale rejection of the logic, aesthetics, wisdom, mathematics, philosophy, biology, theology, economy, sentimentality, politics and law of the world, let alone the religion of the Roman State. The man or woman receiving baptism entered the water naked, in the dark, as a symbol of how much of their former life they carried into the new creation. The martyrs transcended physical concern; they could not be tempted with their own lives. What kind of creature willingly consents to being flayed? Surely not a human being, or certainly not as “human being” had previously been defined. Without the slightest inclination towards anarchy, even the briefest exposure to Late Antique hagiographies suggests 20th century Christianity read Romans 13 with prejudices absent from the hearts of American Forefathers and Church Fathers alike.

A revolution is, after all, a refusal to accept the world at face value; all revolutions call upon higher powers of right and goodness accessible only to the noble, the priestly, the virtuous, the enlightened. Christianity has lately become a thing so wholly characterized by positivity, encouragement, submission, cleanliness, politeness, respectability, dignity, comfort and celebration (even funerals have become “celebrations”) that one has to wonder if we could even imagine a situation wherein righteous behavior meant defiance, disobedience, rebellion, discontent, insubordination, recalcitrance or contrariness. “For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms.” Do we have any room left for this? When I listen to the opening riff of the Savages’ “Shut Up,” I feel as though something is cutting across several hundred years of false smiles and returning me to a place where the wisest man was allowed to say, “Sorrow is better than laughter, for by a sad countenance the heart is made better.” In a recent essay for First Things (“No Enduring City,” August 2013), Hart is critical of the notion that Christianity and Christendom (or any kingdom, for that matter) can ever really get along; for every good Christendom offers God, it takes something back, and eventually the Dove departs the ark and does not return, but blows where it pleases.

…the best moral sense Christians can make of the story of Christendom now, from the special vantage of its aftermath, is to recall that the Gospel was never bound to the historical fate of any political or social order, but always claimed to enjoy a transcendence of all times and places. Perhaps its presence in human history should always be shatteringly angelic: It announces, even over against one’s most cherished expectations of the present or the future, a truth that breaks in upon history, ever and again, always changing or even destroying the former things in order to make all things new. That being so, surely modern Christians should find some joy in being forced to remember that they are citizens of a Kingdom not of this world, that here they have no enduring city, and that they are called to live as strangers and pilgrims on the earth.

Could such thoughts have been far from St Antony’s mind when he walked out of Koma for the last time and set his face for the deserts of Egypt?

Of course, no reflection on the Patristic era really makes punks look admirable whatsoever. In the end, the clawing, abrasive music I have turned to in the last year always leaves me with the cloying, aggravating suspicion that while the punks I am listening to have captured something sonically transcendent, in the event of a war, the side they fight on would probably have my people gibbeted or gigged. They’re all with the New York Times.

IV. The spirit of holy dissatisfaction, the spirit of protest runs parallel to hope in much classic Christian literature. Three years ago, I taught a course on Hebrew wisdom literature at the same time I first taught the City of God. I think now that I had always yearned to hear a holy and righteous assessment of the miseries of life which did not conclude glibly. Even a quick scan of the chapter titles of Books XIX through XXII of the City out to grant some comfort to those in need of refuge from the omnipresent Modern American smile.

“Of the Social Life, Which, Though Most Desirable, is Frequently Disturbed by Many Distresses.”

“…Of the Misery of Wars, Even of Those Called Just.”

“That the Friendship of Good Men Cannot Be Securely Rested In, So Long as the Dangers of This Life Force Us to Be Anxious.”

“Of the Miseries and Ills to Which the Human Race is Justly Exposed Through the First Sin…”

“Of the Miseries of This Life Which Attach Peculiarly to the Toil of Good Men, Irrespective of Those Which are Common to the Good and Bad.”

Nor does the content of these chapters disappoint the titles. The sixth chapter of Book XIX treats on the miseries of the justice system, although Augustine principally highlights the plight of the just judge, who can never know with certainty that he has condemned a man properly.

…judges are men who cannot discern the consciences of those at their bar, and are therefore frequently compelled to put innocent witnesses to the torture to ascertain the truth regarding the crimes of other men. What shall I say of torture applied to the accused himself? He is tortured to discover whether he is guilty, so that, though innocent, he suffers most undoubted punishment for crime that is still doubtful, not because it is proved that he committed it, but because it is not ascertained that he did not commit it. Thus the ignorance of the judge frequently involves an innocent person in suffering. And what is still more unendurable—a thing, indeed, to be bewailed, and, if that were possible, watered with fountains of tears—is this, that when the judge puts the accused to the question, that he may not unwittingly put an innocent man to death, the result of this lamentable ignorance is that this very person, whom he tortured that he might not condemn him if innocent, is condemned to death both tortured and innocent.

We need not confine these comments to the justice system, given that the uncertainty of the aforementioned judge is simply human uncertainty. Friends are no final consolation for the pain of this uncertainty, though, because “…the more friends we have, and the more widely they are scattered, the more numerous are our fears that some portion of the vast masses of the disasters of life may light upon them. For we are not only anxious lest they suffer from famine, war, disease, captivity, or the inconceivable horrors of slavery, but we are also affected with the much more painful dread that their friendship may be changed into perfidy, malice, and injustice.”

I could begin telling you of the rebelliousness and defiance of Ecclesiastes, the outrage and discontent (and not merely with sin and sinners and evil, but with seeing and hearing), although it would do little good. Read a stack of commentaries on Ecclesiastes and you find the book inspires the dormant punk at rest in even the friendliest bosom; no one ever wrote a decent commentary on Ecclesiastes without first throwing every previous commentary under the bus. The three best commentaries on Ecclesiastes I’ve read have virtually nothing in common.

While Iceage or Joy Division might offer some consolation to the dour news junkie, those consolations are the trivial, fading and sensual consolations of the early chapters of Boethius, not prophesies of hope from those seeking grey amnesty in the shadow of the Cross. After the noise, that’s where I return.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs is the director of The Classical Teaching Institute at The Ambrose School. He is the author of Something They Will Not Forget and Love What Lasts. He is the creator of Proverbial and the host of In the Trenches, a podcast for teachers. In addition to lecturing and consulting, he also teaches classic literature through GibbsClassical.com.