Pomp and Circumstance

A poem by seventeenth-century poet Henry Vaughn begins with the line, “I saw Eternity the other night.” It’s a lovely turn of phrase for the way it marries the enduring, the universal, the ideal—“I saw Eternity”—with the passing, the particular, the earthly: “the other night.” Does this not capture a fleeting experience of epiphany that catches us all, one time or another—a sudden tearing of the curtain to glimpse the glory that was there concealed all along?

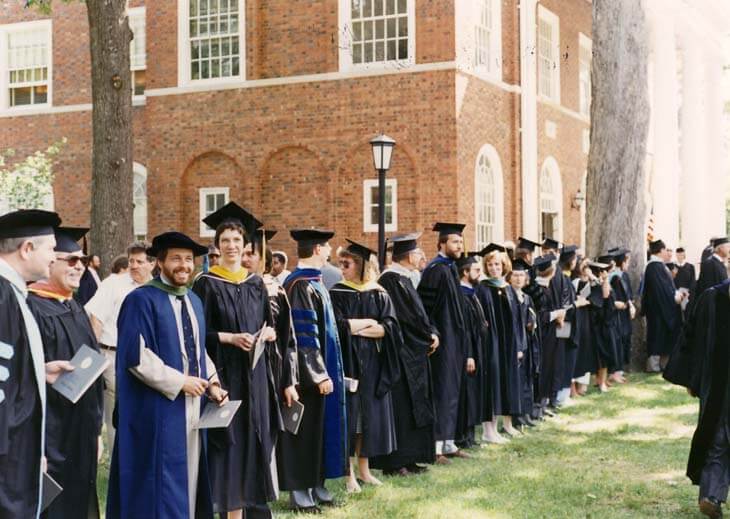

A week ago I watched our graduating class, with robes flapping and tassels spinning, stride up the center aisle, walk across the stage, grasp the diploma, shake the hand, and stand at attention till all the names were read and the applause broke forth. The regalia, the dignity, the strains of Pomp and Circumstance—such a contrast to the drone of pop songs, the distinctive high-school slouch, and the inevitable jeans that characterize ordinary school days—welled up to an “I saw Eternity” moment. The students’ robes and hats, straight shoulders and joyful smiles, seemed to fit better than their everyday-garb, as if revealing the truth of the souls within; the articulate and graceful student speeches seemed more natural than the hallway chatter studded with verbal filler and snarky remarks, as if recovering a forgotten native tongue. You had the sense that this was the frontside of the same tapestry we’d been weaving all year, while seeing only the knotted threads of the back.

But as all this flashed through my mind, so did the misgiving—is it all silliness? Sentimentality?

Here is a paradox: Although we live in a remarkably sentimental spot in cultural history, our culture simultaneously fails to give sentiment its proper due and exercise.

Sentimentality and sentiment, of course, are not the same; they relate as do the worship songs of Chris Tomlin and the cantatas of J.S. Bach, or propaganda and rhetoric, or Velveeta and a sharp, aged English cheddar. Sentimentality is a reductive, processed, mass-marketed imitation of a true, good, and beautiful emotional response to reality.

Cultural arenas from political rallies to chick-flick plot lines summon sentimentality through reference to elusive, idealistic pasts and narratives, and use it to justify consequential choices. This sentimentality (a kind of rhetorical pathos) has little grounding in the other modes of persuasion—logos, or reason, and ethos, or trustworthiness of character—that bolster true wisdom.

However, in situations when sentiment could be grounded in reality and wisdom, it is often mocked. Thus, the sentiments of honor, joy, and gratitude that ought to accompany marriage are mocked through cheap and vulgar jokes about loss of freedoms or negative stereotypes. The sentiments of dignity and value that ought to attach to one’s work are mocked and replaced by “climbing the corporate ladder” or “working for the weekend.” The sentiments of indebtedness and responsibility that ought to accompany national observances are mocked by garish red, white, and blue get-up and glib God-bless-America’s. The sentiments of reverence and awe that ought to accompany the Lord’s worship are mocked by reduction to marketplace modeling and musical manipulation. And the sentiments of commemoration and commendation that ought to accompany a graduation ceremony are too easily mocked by poking fun at the funny clothes, clichéd music, and grandiose declarations.

Mockery always claims to expose the true condition of things, but it lies. While sentimentality employs emotion like vapor to hide a sham, sentiment employs emotion like adornment to make visible the reality. If sentiment, and its natural outflow into ceremony, are discarded, then we see not more clearly, but less.

To mock sentiment and refuse ceremony is, in fact, to be blinded by a self-importance that itches to put down anything else of eminence, as C.S. Lewis observes in his discussion of epic’s grand style in A Preface to Paradise Lost:

A celebrant approaching the altar, a princess led out by a king to dance a minuet, a general officer on a ceremonial parade, a major-domo preceeding the boar’s head at a Christmas feast—all these wear unusual clothes and move with a calculated dignity. This does not mean that they are vain, but that they are obedient; they are obeying the hoc age which presides over every solemnity. The modern habit of doing ceremonial things unceremoniously is no proof of humility; rather it proves the offender’s inability to forget himself in the rite, and his readiness to spoil for every one else the proper pleasure of ritual.

As the end of the academic year approaches for many of us, or is being remembered by others, may the fuss and feathers, the pomp and the circumstance, be fit reminders of the pleasures, the epiphanies, the wisdom to which sentiment and ceremony may awaken our too-dull perception.

Lindsey Brigham Knott

Lindsey Knott relishes the chance to learn literature, composition, rhetoric, and logic alongside her students at a classical school in her North Florida hometown. She and her husband Alex keep a home filled with books, instruments, and good company.