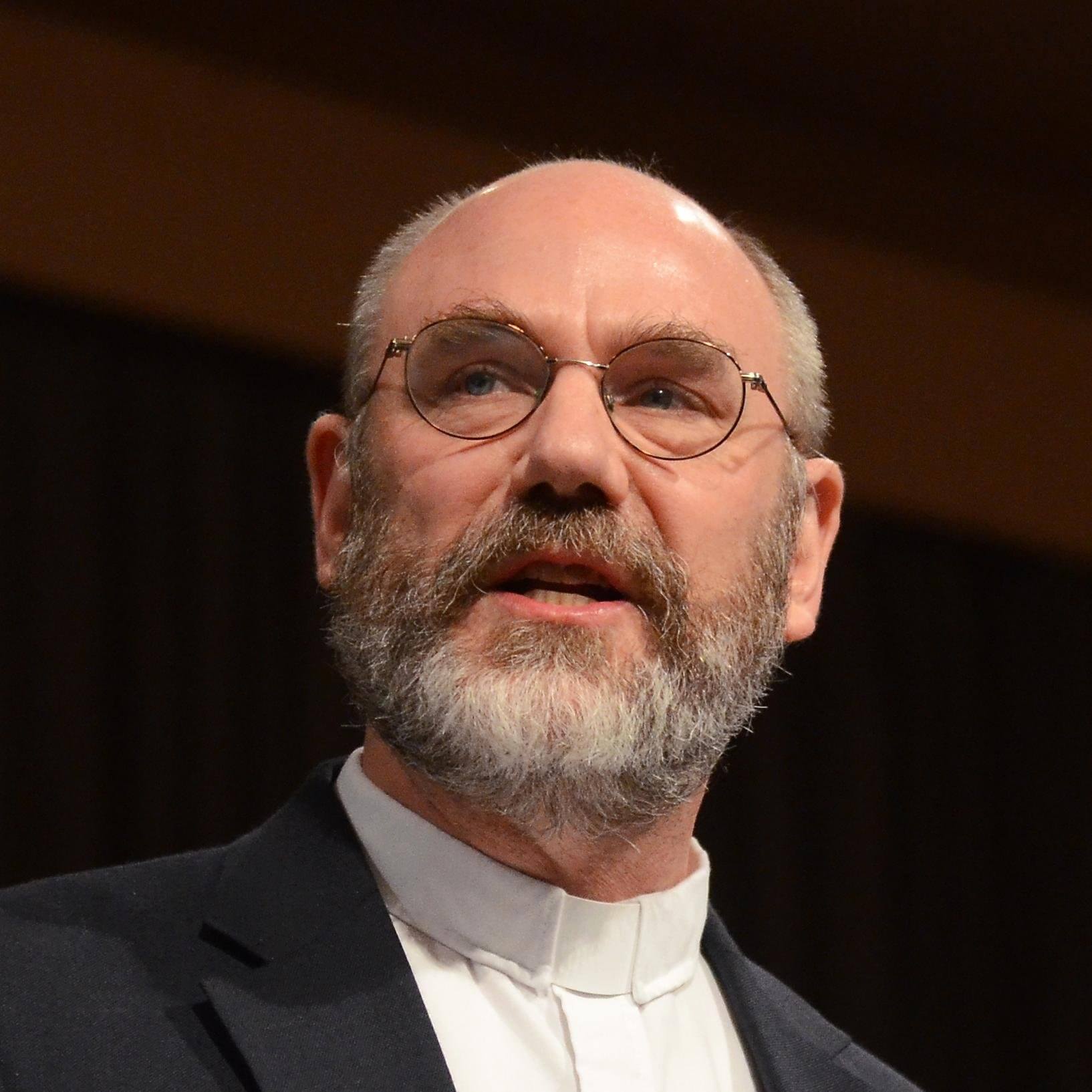

The Personalism Of Peter Leithart

How to point with both hands.

“While there are many theological matters upon which I heartily disagree with Peter Leithart, he is yet one of the finest literary critics writing…” is not the first line of this article. This is the most important thing I have learned from Peter Leithart. The second most important thing I’ve learned from Peter Leithart is not to talk about myself. As you can already tell, I have some work to do.

In the age of the internet, too many theologians court celebrity by constantly yammering about themselves, their feelings and their ideas. They begin essays and blog posts with lines like, “I was thinking about Dante the other day…” or “Someone asked me what I thought about…” or “I have a thing or two to say about the current…” or “I made a few remarks about my…” or “I would like to deal with Smith’s response to my review of…” Often, though not always, such theologians and cultural critics are more interested in putting themselves forward as interesting personalities than they are in talking about other people’s ideas. The difference between theologians who are interested in others and theologians who are not emerges subtly in the way either frame their thoughts. A vast chasm separates the self-oriented “I was reading Augustine’s book about marriage the other day and found a passage I thought worth quoting here…” and the more personal “In his brief work On Marriage and Concupiscence, Augustine claims…” The former quote is about the reader of Augustine, the latter quote is about Augustine. Peter Leithart never explained this principle of critique, though he never had to.

If you read Leithart’s blog, you’ll find he rarely refers to himself. He is far more interested in the books he reads than in his own responses to those books. When he does voice his opinion of a book, he renders judgment but does not often refer to himself rendering judgment. As opposed to saying, “I find Hart’s claims dubious because they do not easily square with Paul’s teaching on…” Leithart usually writes, “Hart’s claims are dubious, though, given St. Paul’s teaching on…” The first example is about the judge and the act of judgment, but Leithart makes himself invisible and sets the truth on a pedestal. The author of “I find Hart’s claims dubious…” is more likely to inspire readers to come away saying, “Well, the author of that essay is quite sharp,” whereas the reader of Leithart’s claim will come away saying, “Hart’s claims on such-and-such a matter are not appropriately Pauline.” Leithart wants to illuminate. He could care less whether you think he’s brilliant. Like the best original film scores, you don’t notice Peter Leithart as Peter Leithart. As opposed to using his left hand to point at his right hand pointing at his subject, Leithart points with both hands.

Leithart’s genuine interest in his subjects means he is far less prone to state his objections up front, if ever. Leithart is Protestant, and so if he sits down to review a book written by a Catholic, he typically assumes his readers know he objects to a Catholic writer’s take on Mary, icons, and so forth. He does not endlessly mention his hesitations, or inform his readers that while such-and-such a writer is brilliant, he gets a good bit wrong, too. A fine example of this is Ascent to Love, his commentary on The Divine Comedy. The chapter on the Purgatorio begins with the briefest survey of tried-and-true Protestant opinions on the doctrine of Purgatory, but they are not revisited again, nor does he feel the need to make a case against Purgatory before discussing the canticle. No doctrine of works is enumerated, no fussy jokes made at the expense of Dante, who is not around to defend himself. Instead, Leithart leaps directly into the Purgatorio, explaining theme and trope and structure. Leithart seems comfortable with the fact that brilliant men are sometimes wrong, but that their wrongness need not be belabored in order to discuss their brilliance. Beginning a review or essay with, “So-and-so gets more than a few things wrong, though he is helpful on the matter of…” is a way making the personality of the critic supreme, as though classical works need critics to curate the intellectual sins of classical writers in order to make them safe.

In all of this, Peter Leithart is a far more personal writer than many of his contemporaries. Why, though, is making your personality invisible more personal than constantly referring to yourself? The difference between the self and the person is an infinite difference, if the great twentieth century investigators of personhood (Lewis, Percy, Berdyaev) can be trusted. A self is a truncated, infertile image of the whole person. Paradoxically, we may only become whole persons when we cease thinking about our personhood. In the eschaton, we will be full persons because we cease looking at ourselves and look only at God, in Whom is hidden our person. Like Orpheus, we can have what we want only when we turn our eyes from it. While our eyes are directed out of Hell and towards the Light, we are whole. When we look back at what we want, it falls into darkness and obscurity. In directing his gaze toward his subjects, Leithart becomes a fuller person and gains distance from his self.

To know Peter Leithart as a generous critic and a humble reader is to know him in a far more personal way than merely knowing him as the man who likes or doesn’t like this or that. I don’t know much of Peter’s taste, but tastes are always changing. I know his virtue, though, and his virtue won’t pass away.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.