On Pacifism, Real And Fake

Around ten years ago, I spent a little time claiming to be a pacifist, and then one day I took a look at myself and said, “In what sense are you a pacifist? Be honest. You’re not a pacifist.” Aside from a few dozen comments I had made on social media, and a few arguments I could summarize, there was simply no evidence that I was a pacifist. At best, I simply no longer enjoyed violent movies as much as I had as a teenager.

Anyone who becomes deeply acquainted with the first five hundred years of Church history will encounter Christian pacifists. These encounters will more often occur in history books than in theology lessons, although the Church Fathers may certainly be depended upon for a succulent quote or two supporting non-violence. Any number of late antique martyrs (perhaps St. Polycarp of Smyrna, most memorably) refused any form of politicking to secure their release from jail or legal exoneration, preferring to preach the Resurrection with their blood rather than mere words. Scores of similar stories are easily discoverable in The Golden Legend or various hagiographies, and the stories are often drawn in vivid colors, married to harrowing, horrifying accounts of mutilation and torture which rattle the nerves and upend the heart. To deny the reader his profound response is unreasonable.

That said, pacifism is not so much an ideology as it is a way of life. The fact that a man admires monks does not make him a monk. The fact a man reveres the mysticism of the Desert Fathers does not make him a hermit. One does not become a monk merely be reading and enjoying The Rule of St. Benedict, and neither does he become a pacifist by reading a book by John Howard Yoder. By the time most men read The Rule of St. Benedict, they have already made oaths which preclude them from becoming monks. A young man may become a monk if he chooses, but he must choose, and the married man has chosen not to be a monk, regardless of his admiration for Francis, Dominic, and St. Anthony of Egypt. The same is true of pacifism. For the married man who lives in the city, keeps his money in a guarded bank, enjoys the protection of the police, and whose way of life depends upon the standing threat of coercion and violence against lawbreakers, the claim to be a pacifist is simply a fantasy. This is not to say that pacifism is impossible or that it is philosophically untenable, but that the average city-dweller has made oaths, both tacitly and explicitly, which preclude him from claiming he is opposed to all forms of violence. He might admire people who have made painful commitments to non-violence, and he might see the beauty of those who willingly accept martyrdom, but he is no more a pacifist than he is a prophet, a priest, a stylite, or a firefighter battling a four-alarm fire. He must humbly live with the fact that he did not choose a more difficult and (perhaps) more pious way of life.

The fact that pacifism is neither wrong nor impossible does not mean all men must be pacifists. Much like the performance-art prophesy of Jeremiah or Hosea, the pacifist’s way of life testifies to another and better world, and his testimony is neither more nor less powerful than the performance. Prophesy is as prophesy does, much like pacifism. But Christians are no more required to be prophets and monks than they are required to go to seminary. Is the life of a Gospel minister more demanding than the life of a baker? I imagine so, given that the livelihood of a minister depends upon maintaining a high moral standing, which is not true of a baker. Nonetheless, a man is not necessarily required to do the most difficult thing he thinks noble. Christ tells the rich young man, “If thou would be perfect, go and sell what thou hast…”, and while Christ did not demand such perfection of everyone, a great many men have sold all they had and given it to the poor. Francis of Assisi took Christ at His word, at very least.

It is upon this point that I find Facebook-pacifism more than a little risible. For the Facebook-pacifist, I would like to know: What is the difference between a pacifist and someone who thinks he is a pacifist? Was there anyone who thought he was a pacifist and was wrong? Is it difficult to be a pacifist? How does one labor to become a better pacifist? Who holds a man accountable for being a pacifist? How has being a pacifist required you to suffer? Given that the life of a non-pacifist is easier, do you sometimes wish you were not a pacifist? Are you tempted to go back to your old way of life? I do not ask these questions rhetorically, though I do not think it too much to expect a man who claims a high-minded identity to have suffered something in order to sustain his claims. However, if it cost a thousand dollars to be a card-carrying pacifist, I do not think they would need to make very many cards.

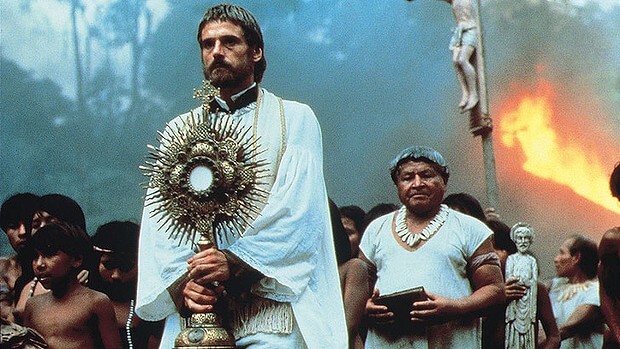

The more stories one reads of genuine pacifists, by which I mean men and women who eschewed the protection and pleasures of the city, suffered for their convictions, and condemned themselves as great sinners, the more one realizes just how strange pacifism actually is. At the end of The Mission, when Jeremy Irons marches bravely to his death while dressed in his white vestments, the anger and numinous terror the viewer feels is the mind-bending strangeness of non-violence. For the Facebook friend whose pacifism pops up only in response to stories about the US military, and whose pacifism is mainly confined to snarky comments and quotes from Hippolytus and Tertullian, no such heady whiff of the uncanny attends— and neither do such pacifists quote much from Hippolytus or Tertullian on the subject of, say, gender roles.

This may seem to have little to do with the classical classroom, though I believe a good education into late antiquity will bring the student to a powerful encounter with willing martyrs like St. Polycarp. A terrible nominalism pervades the spirit of our age, and a man is tempted to believe that merely wanting to be something is sufficient to make him that thing, apart from nature, apart from suffering, apart from ritual, apart from reality. Teaching our students to set high ideals beyond themselves is simply another way in which education is fundamentally an act of humility and repentance.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs is the director of The Classical Teaching Institute at The Ambrose School. He is the author of Something They Will Not Forget and Love What Lasts. He is the creator of Proverbial and the host of In the Trenches, a podcast for teachers. In addition to lecturing and consulting, he also teaches classic literature through GibbsClassical.com.