Man As Microcosm, Part One: Gaining Your Soul And The Whole Cosmos Within It.

When man rises to meet God, and when God condescends to meet man face to face, a divine promise is fulfilled which was written in the heavens "before the foundation of the world."

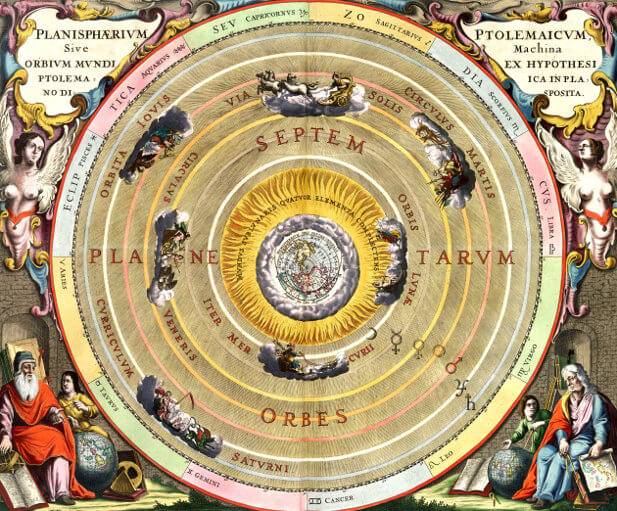

Seven planets. Seven virtues. Seven days of the week. While teaching Dante’s Paradise last year, I canvassed friends for connections between all three sets of seven. One friend (Jeremy Downey, whom I feel I ought to name so he can receive credit for the remarkable discovery he made, which will be detailed in a moment) commented that ancient pagan societies understood that each of the spheres were married to particular days of the week. Some of the marriages are obvious (Saturn to Saturday), although some have been obscured by time and translation (Mars to Tuesday). Here is the run of things:

At first glance, there seems little correlation between the progression of the days of the week and the order of the spheres. The days of the week appear shuffled up like cards. On second glance, though, the days of the week are thematically organized.

As the days of the week move from Earth towards the heavens, each day progresses into the day which follows it by four steps. Thus, Monday is four steps away from Tuesday, Wednesday is four steps away from Thursday, and so forth. However, as the days of the week move from a heavenly direction toward Earth, each day progresses into the day which follows it by three steps.

If this is not clear, try this: put your finger on Monday. Moving your finger from Monday to Wednesday above it is one step. Moving your finger from Wednesday to Friday above it is the second step. Moving your finger from Friday to Sunday above it is the third step. Moving your finger from Sunday to Tuesday above it is the fourth step. Thus, from Monday to Tuesday is four steps. This will work with every day of the week wherein the day which follows it is up.

Again, Saturday is followed by Sunday, and yet the movement of your finger is from the place of the heavens toward the Earth. Put your finger on Saturday. If you move your finger from Saturday to Thursday below, this is one step. From Thursday to Tuesday below it, step two. From Tuesday to Sunday below it, step three.

As the things of Earth move towards the heavens, they move by steps of four. As the things of heaven move towards the earth, they move by steps of three. Of course, three is a number signifying God, who is Father, Son and Holy Spirit. At the same time, four has always been a number associated with both the Earth and man. The Earth has four corners, but man has four corners, as well. If a man spreads his arms out wide, the distance between his fingertips is equal to the distance between his head and his toes. Because man is as high as he is wide, the Medievals knew man to be square shaped. The Earth possesses four winds, and we recognize four cardinal directions. In The Discarded Image, Lewis describes the Medieval notion that every day might be broken into four parts, each of which was suitable to a separate humor of man. Likewise, there are four elements which make up man…

What’s remarkable about Jeremy’s realization is that the progress of the days, from earth toward heaven or from heaven toward earth, is numerologically Christian and yet lay more or less dormant within pagan philosophy for centuries.

As Dante progresses through the spheres towards the Empyrean, he is recreated in his adoption of the seven virtues. Each of the spheres governs the life of man inasmuch as each sphere inclines a man toward the virtue appropriate to that sphere (Dante learns Faith in the sphere of the Moon, Hope in the sphere of Mercury, Love in the sphere of Venus, and so forth).

However, the recreation of a man moving from Earth toward Heaven also suggests something profound about the original creation of man. Between the lines of Dante’s text, and in the margins of Dante’s ideas, emerges an account of the creation of the Earth and man which I have never encountered anywhere else.

It is appropriate for man to be recreated as he moves towards Heaven, because he was first created as he moved away from Heaven.

Before the Earth was truly the Earth, it was “without form and void,” an expression so familiar to us we scarcely investigate it. The formless Earth is chaotic. The raw matter which will become the Earth has no idea or image impressed upon it. In some sense, the Earth is not exactly the Earth when it is “without form,” for the word “Earth” itself suggests a form impressed upon matter.

It seems that Dante represents each day of the creation week as a movement of this raw matter through the spheres. Just as the ascending Dante learns a new virtue as he passes through each sphere towards Heaven, so in the creation week, the formless matter gained a new virtue, a new image, a new knowledge as it passed from one sphere to the next.

Man is created from the Earth, but man might also be seen as a separate Earth, a rational Earth. The creation of the Earth is not final until Man has been installed in the rest of the Sabbath, wherein he receives the freedom appropriate to his status as image-bearer of God. Even God’s day of rest from His creation paradoxically transforms His creation.

Given such an understanding of the creation week, man is a microcosm inasmuch as the goodness of the whole cosmos has been impressed upon him (Man as faithful Moon, Man as hopeful Mercury, and so forth). To behave according to virtue is to weave oneself seamlessly into the motion of the spheres. It is no surprise that the man in sin often feels as though he has not merely wronged his neighbor and himself, but the universe entire, and the universe stands opposed to a man in the act of sin. “I defy you, stars!” yells Romeo, not so much spurning fate as declaring war on God’s governors. Boethius notes in The Consolation that because God is simple, to attain one virtue is to attain them all. A man cannot be faithful but not loving, courageous but not hopeful. On the other hand, the “enjoyment” of one vice tends to cut man off from the possibility of “enjoying” the pleasures of other vices. A man might “enjoy” being lazy, but in doing so, he cuts himself off from the possibility of “enjoying” wealth.

Dante’s presentation of man as microcosm is not particularly radical given Moses’ affirmation in Genesis that man is not created from nothing, but from prior substances. If man is made at least partially of prior substances (clay), we might also entertain the notion he is also partially made of prior images and ideas (the faith of the Moon, the hope of Venus, etc). At the same time, man’s composition is altogether novel in that he is made a living spirit by the breath of God, and given the freedom of the Sabbath which instills in him a perfectible spirit, which not even the angels possess. “Man can fall and be redeemed. From this point of view man is worth far more than the angels,” notes Rémi Brague in The Wisdom of the World.

“For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul?” asks Christ in Matthew, to which Dante affirms, “And what profit it is if man gains his soul and the whole cosmos within it!”

Finally, within the model of the week and the spheres which attend it, there seems something prophesied about God’s condescension to man, and man’s ascension to God. When man rises to meet God, and when God condescends to meet man face to face, a divine promise is fulfilled which was written in the heavens “before the foundation of the world.”

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs is the director of The Classical Teaching Institute at The Ambrose School. He is the author of Something They Will Not Forget and Love What Lasts. He is the creator of Proverbial and the host of In the Trenches, a podcast for teachers. In addition to lecturing and consulting, he also teaches classic literature through GibbsClassical.com.