Justice, Faith, And Moderation In The Song Of Roland.

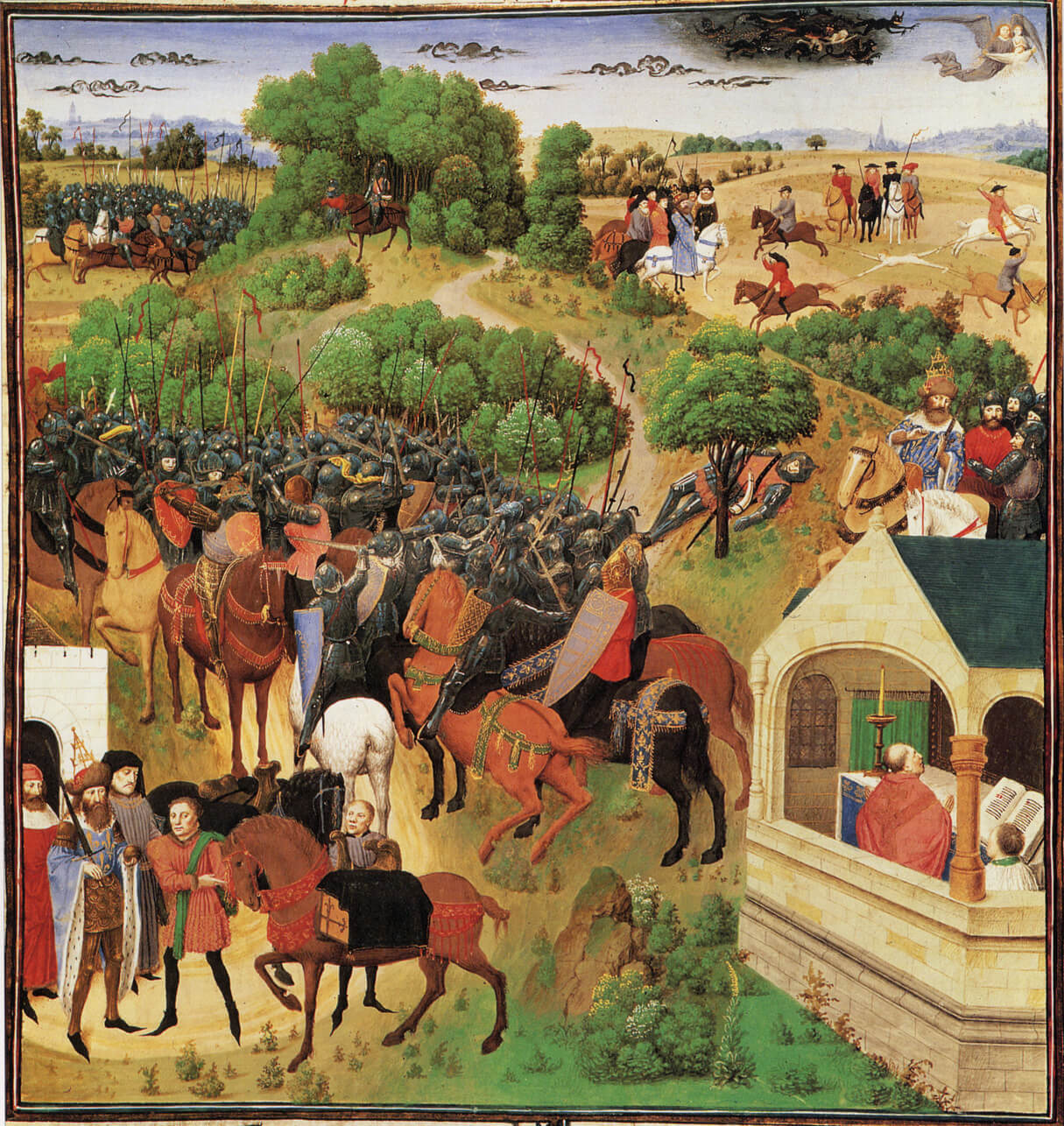

A good portion of The Song of Roland is devoted to describing the brutal, awful destruction of the human body. This violence is bookended by court scenes— the first are set in the Muslim stronghold of Saragossa and the last are set at the trial of Ganelon in Aix, Charles’ capital. Given the reputation of the book, many students are apt to rush through the opening to arrive at the action, though the real guts of the book come at the beginning. I’ll confess that just war is not a subject I’ve strenuously studied, though in the reading I have done, The Song is rarely invoked. This is unfortunate because The Song upholds one of the most vigorous, satisfying theories of just war you’re apt to find in an epic.

I’m going to entirely disregard arguments about the historicity of the book and rely wholly on the events as they are described by the poet.

After fighting to reclaim Christian land from Muslims in Spain for seven years, Charles’ army has one remaining battle to fight. The book opens with the Christian army encamped at Cordova, a wealthy city at the base of a mountain, atop which sits Saragossa, a Muslim city ruled by Marsilla. In Saragossa, Marsilla convenes his court to figure out what to do about the Christian problem just outside the city gate. His wisest advisor Blancandrin proposes they offer Charles three things: gold, a promise Marsilla will convert to Christianity, and hostages to prove the offer of conversion is made in good faith. The key to the offer is in the specifics of Marsilla’s proposed conversion. If Charles returns to Aix, Marsilla will follow him a month later and accept baptism on Michalmas. The promise is not genuine, and Marsilla has no plans to convert, and the hostages will be lost, though they won’t have to deal with Charles. His soldiers will return to their homes and once the trick is discovered, it will take Charles a long time to reconvene everyone. The Muslims might have as much as a year to make a better plan. Marsilla agrees and sends Blancandrin to Charles’ camp to offer him terms.

Charles hears the terms, then convenes his court for advice. Roland wants to reject the offer because Marsilla has sued for peace before, then mercilessly slaughtered Charles’ ambassadors who came to meet Marsilla to secure the agreement. Roland claims that Charles is obligated to pursue justice for the dead and make war on Marsilla. However, the sticky issue is the hostages Marsilla has offered to vouch for his promise to convert. Charles’ other advisors claim it would be a sin to make war on Marsilla because the hostages must be treated as iron-clad proof the terms are offered in good faith. The Christians would not be acting mercifully if they rejected an iron-clad suit for peace.

Readers are often baffled by what happens next. Charles unhappily accepts Marsilla’s offer. Even as he sends emissaries to accept the deal, he knows it will all go badly. He knows Marsilla is lying. Why then does he accept the deal?

For Charles, acting justly and acting strategically are not synonymous. A good strategy is not always virtuous; the point of war is not necessarily to win. Acting justly means submitting the war effort to God that God might fight on their behalf. All virtue is holy weakness; the weakness of justice is simply faith that something other than horse and chariot bring victory. Marsilla claims he wants the war to end and is willing to offer hostages as proof of this. Charles cannot make a preemptive attack on the basis of his suspicion the offer is bogus, though. He is a man bound by time, finite, and the demands of Christian gentleness and meekness mean he is not allowed to treat his enemy as a liar until he is proven a liar. Because Charles’ suspicions could be wrong, a preemptive attack against a man suing for peace would be arrogant. Charles cannot read Marsilla’s heart, only God can, and God may have softened it.

However, God calls Charles to an even deeper humility by sending him dreams which clearly indicate Marsilla is lying. Again, modern readers are baffled at why Charles does not act on the information presented in these dreams. In the remarkable The Sense of the Song of Roland, Robert Francis Cook suggests that while secularists often depict the Medieval period as a time when superstition ruled, the opposite seems true of Charles. He is a reasonable man living in a reasonable age, beholden to his advisors and the rules handed down by his court. Claiming that a private message from God privileges the Christian army to preemptively attack men suing for peace (who are willing to backup the suit with the lives of their own sons) is immoderate and leaves the Christian court open to horrible corruption. God gives Charles visions of Marsilla’s treachery so that we, the reader, might see Charles’ profound commitment to justice. Though God confirms Charles’ suspicions are right, Charles must trust God as he gives himself up to a trap.

All this might lead someone to ask, “If justice is holy weakness, then why fight with pointy swords? Why not use dull swords in the faith that God would make them sharp in the heat of battle?” While I can respect the reductio ad absurdum as a logical argument, I’m not convinced the regular invocation of it is anything more than a rejection of moderation, prudence and self-control. But still… why the pointy swords?

The poet of The Song presents the Holy Roman Empire as a synergistic relationship between God and man. The good emperor does not sit on his hands, waiting for angels to arrest the criminals, but the good emperor does rely upon the angels to sort out the guilty and innocent in a trial by ordeal. The good emperor does not wait for bread to fall from the sky in a time of famine, but he does take Christ’s command “You feed them” to the apostles quite seriously. A well run state is a partnership between man and angel, law and creed. Man is always going to be tempted to do too much, to rely on himself too much. In condescension to our weakness, God is willing to richly reward very small acts of faith and holy weakness, like those of Charles as The Song gets started.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.