Interview With A Falsely Imprisoned Theologian: A Short Story

Written by Horace Gaines

Around noon on October 17th, 2009, August Bruce left his office on the Duke campus after mentioning to several colleagues that he was not feeling well. August was an associate professor of historical theology and had worked at Duke for fourteen years. He was respected by his colleagues, but not well-liked by his students, who complained that he was overly opinionated and a more than a little egotistical. “He knew a lot about theology, but he took every chance he could find to complain about movies, pop music, especially rap music, clothes, fashion trends,” said Marco Weaving, a former student who now owns a book store in Chapel Hill. “He was always a little irritated about something that had just happened.” In his time at Duke, Bruce’s office was vandalized four times. His car was vandalized twice. Bruce complained that students had done it but had no evidence. Colleagues who heard him complain of an upset stomach were among the last people to see August. When Dana Bruce returned to their home on the evening of October 17th, August was not there. She reported him missing the following day.

A neighbor claimed to have seen August in the late afternoon of the 17th. James Cochrane, whose home is directly across the street from the Bruce residence, said he witnessed August exit his home with another man who was dressed in blue jeans, sunglasses, and a green flight jacket. Both men got in a black BMW, August in the passenger’s seat, and then drove away. An extensive search was conducted in the quiet neighborhood where the Bruces lived and more than a hundred leads related to the black BMW were pursued by the police. When the possibility arose that his disappearance was a kidnapping, and that the kidnapping might be politically motivated, the FBI became involved.

Dana hired a private investigator. She searched her husband’s office, his car, every box of papers, every square inch of their home looking for a clue as to his disappearance. He had almost certainly been home on the afternoon of the 17th. “The garbage was full when I left for work that morning, but he had taken the garbage out at some point in the day. He replaced the liner. I found a candy bar wrapped in the bottom when I searched it. He ate a Kit Kat bar.” She also found a receipt for a gas station they frequented. Apart from this, there was nothing to go on. August Bruce had simply vanished into thin air.

After a year, Dana resigned herself to the fact she would never see him again. “I knew he was either dead, or there was some terrible secret in his life which he never told me about. I thought he might have had a second life. I loved August. He loved me. But even after 23 years of marriage, I sometimes felt as if I didn’t know him.” In all her searches through August’s things, Dana never discovered anything which gave her pause or alarm. Her husband had been a theologian, an avid reader, a fan of classic films, something of a crank and a stodgy traditionalist. Nothing Dana discovered in his closet, his dresser, his office, his desk, or the glove compartment of his car challenged her impression of him.

And then, three years to the day after August disappeared, he reappeared.

At Chez Monique, a small café in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, August Bruce slowly came to himself. A bowl of warm rabbit stew sat before him. He groggily asked a waiter where he was and the waiter told him the name of the café. “I’ve been in prison,” August told the waiter, then he began to shout, then he collapsed on the ground.

Despite his claim, August Bruce did not look to have been incarcerated. His face was freshly shaved, his hair lately cut and styled, and he was dressed in a white Bottega Veneta jacket and linen slacks. One diner told a Paris newspaper, “I was sitting just a few feet away from him at dinner. He was slumped over a little, talking to himself. Then he began to get very excited, very animated, though his speech was slurred. I thought he was drunk.” The waiter claimed August arrived at the restaurant with a man in jeans, sunglasses and a green flight jacket. “Mr. Bruce looked lost,” said the waiter, “and the man with him placed an order, then he must have left, but I did not see him go.”

Bruce spoke briefly with authorities in France, then returned to the United States where he was reunited with Dana, whose astonishment that her husband was alive was matched by her disbelief that he was still of sound mind and body. His hair had turned silver. “He had changed. I could see it in his face when he stepped off the plane, before he said a word. He was not the same,” said Dana, carefully measuring her words. “There was something sadder about him. But gentle, too.” After three days with Dana in Durham, August was interviewed extensively by the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security, who requested he not speak with the media until a later point. After these interviews, the FBI housed both the Bruces in an undisclosed location for six months, during which time the nature of August Bruce’s three-year disappearance was still a mystery.

Last month, August Bruce returned to Duke University for the beginning of the Fall term. A small party was held in his honor. August had been given clearance by the FBI to speak with the media and tell his story, but no one in his office had any idea what he would say. “The party was uncomfortable for everyone,” Bruce told me.

As I prepared to do the interview, I will admit that my greatest curiosity was the man in the green jacket whom the Bruce’s neighbor had seen, and who then seemed to resurface three years later in Paris. The man in the green jacket had the aura of a demon. He was evil, did what he wanted, and could not be caught. I wanted August Bruce to tell me more about him. How had he lured August into that car? With what promises?

Since his reappearance in Paris, August Bruce has become something of a celebrity. He has not achieved renown for his beauty, his talent, or his power. People are simply fascinated by his mystery. He has become famous for having a secret, but who could say whether his secret would be any good? On a professional level, I felt lucky to have landed the interview, but on a personal level, I was no different than anyone else in the country. I just wanted to know what happened.

Dana was right. August Bruce looked like a man who had seen something. He appeared harmless, conquered, but unafraid. We sat down to talk on a rainy Wednesday afternoon at the kind of wood and brass bar you hope Duke profs haunt.

GAINES: There are a few people who have already heard your story, August— the FBI, your wife, presumably— but you’ve had a number of months to think about how exactly you want to begin describing your ordeal.

BRUCE: I have gone back and forth several times on what my opening line ought to be.

GAINES: Well, how does that opening line go?

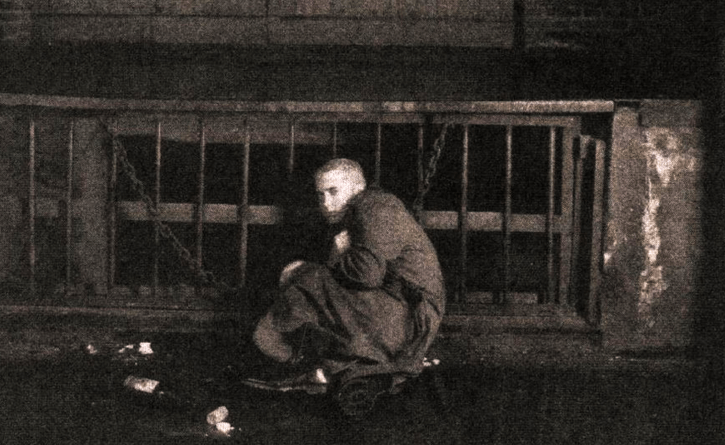

BRUCE: I was kidnapped and held in a black-market prison for three years. I say “prison,” though that word will bring the wrong images to mind. It was actually a converted hotel, I think. I was in a room with a single bed, a bathroom with a shower and a sink, a dresser and a desk. The dresser and desk were empty. There was no television. The shower worked well, though. The water was usually warm.

GAINES: Who brought you food?

BRUCE: The door to my room was locked, but there was a revolving window installed in the door which could be spun around so that objects could enter and exit the room without anyone seeing in or seeing out. My meals came twice a day through that window. A good, large breakfast early in the day and a large dinner late in the day.

GAINES: You saw no one for three years?

BRUCE: That is correct. I did not speak to another human being or see another human face for three years.

GAINES: To subject another human being to that kind of loneliness seems so cruel… I don’t mean to make light of your pain, but you just said now that you were served a “good, large” breakfast. What does that mean?

BRUCE: Breakfast was typically quite hearty. Half a grapefruit. An English muffin or toast, always served with cultured butter. Sausage, bacon, or scrapple, and the scrapple was really excellent. The cook used a very mild fresh sage in the scrapple which I absolutely adored. On occasion, there was quiche, typically made with Gruyere, white peppercorns and some kind of meaty purple olive with a name I do not know. Every great once-in-a-while, I was given crepes with apricot jam and whipped cream. I believe the crepes may have been served to me on my birthday, but I could not be for certain, because I lost all sense of time. I did not see the sun for three years either, and my room had no clock.

GAINES: And dinner?

BRUCE: Dinner was ample, as well. Pork chops with apple sauce and potatoes gratin. Salad nicoise. Various terrines served with toast and roasted vegetables. The chef was something of a gourmand, I believe.

GAINES: Why were you were fed so well?

BRUCE: With a single exception, I have just told you all there is to say about the prison and prison life. There were no books in my room. Nothing to write with. Nothing to write on. I ate my food very slowly. I prayed for every meal three times. In the beginning, at the mid-point, and when I finished. I spent two hours every day eating breakfast, and another two hours eating dinner. I would meticulously wash my dishes in the sink in the bathroom, using hand soap and my palms to scrub the plates, the saucers, before returning everything to the window. My supplies of shampoo and soap and toilet paper were restocked regularly, as well. New bottles of everything appeared once a month, and I put the empty bottles in the revolving window so someone could throw them away. Fresh towels arrived. Fresh sheets for my bed. I put the old towels and the old sheets in the window and someone took them and washed them and returned them. Fresh towels and sheets arrived once a week.

GAINES: Was your bed comfortable?

BRUCE: Not especially, but neither was it terrible. The mattress was reasonably firm. I was given new pillows once, a little more than halfway through my stay, I believe.

GAINES: Could you hear anything through the walls?

BRUCE: No. But there is another detail about the room which I haven’t yet mentioned. And the whole point of my incarceration is bound up in this detail.

GAINES: Please.

BRUCE: There was music piped into my room through a number of speakers installed in the walls. This music was the reason I was kidnapped and imprisoned. The decent food, the decent arrangements existed merely to serve this music to me in a more unavoidable way.

GAINES: I am afraid to ask. What was the music?

BRUCE: About an hour after I arrived in the prison, a CD began playing in my room. That CD would play on repeat, all day, every day, for the next three years of my life. The volume the CD played at never fluctuated. It was not played loud, but just below listening level. Had I wanted to listen to the music for enjoyment, I would have turned the volume up just a little higher than it was set. I could hear it clearly, though. The CD was seventy-two minutes and two seconds long, which means that, if you include my hours asleep, I heard the CD over twenty-one thousand times while imprisoned.

GAINES: What was this CD?

BRUCE: The Marshall Mathers LP by Eminem.

GAINES: My God.

BRUCE: About two years before I was taken, I published an essay on the subject of censorship in National Review which contained a single, biting reference to Eminem’s music. Rap music was hardly the subject of that essay, though. At the time I wrote it, I had probably only heard ten seconds of an Eminem song. I was 45 years old. I listened to Bach, Durufle, Debussy. I knew Eminem was a household name and he was well known for writing exceptionally violent and nihilistic music which made light of rape, murder, and torture. However, I’d never really listened to his music. I had scanned the lyrics to a song of his once just to see what the fuss was about, but that’s all.

GAINES: What went through your head when the CD began to play for the first time?

BRUCE: I immediately thought of my article. The moment I realized an Eminem album was playing in the room, I remembered those few lines from that National Review essay. I remember thinking something like, “I’m going to have to listen to this music for a whole week, and then someone is going to kill me.” I figured it was all some kind of psychological torture which would culminate in my being shot.

GAINES: Remarkable.

BRUCE: Several months in, I broke.

GAINES: What was the breaking point?

BRUCE: I don’t know now if it was intentional, but in my third or fourth week, the music stopped for about two hours. That was the first and only reprieve. After the last track, the music stopped and did not restart. When it stopped, I wept. I had already begun asking God to end my life. I may have even been willing to end my own life in that dark hour, if only I had the means to do it. But that silence… was the purest, most heavenly thing. In that silence… I understood that silence was simple, and that silence was not nothing. The simplicity of silence seemed divine to me, as though God Himself was directly known and experienced in the act of partaking of silence. I had never known such depths of relief as I did in the moment the music stopped for those two hours. Then the music began again, and never stopped. When the music began again, I broke.

GAINES: What do you mean?

BRUCE: I flew around the room in a rage. I slapped myself, hit myself. I cursed God. I pronounced curses against God and dared Him never to forgive me. I said, “I hate you, God, and when I tell you I repent of saying this later, do not believe me. I command You not to forgive me later, not even when I beg you. I swear to You, by Your Holy Name, that I will never forgive You for allowing this to happen to me. The truth is that I hate You for allowing this to happen. It is the truest thing I have ever known.” I could blot out the music if I screamed at the top of my lungs. I screamed so long that I fainted. I woke spitting blood. Once, I tried to stop my ears up with cotton from the pillows, but someone gassed the room, I fell asleep, and when I woke the cotton was gone.

GAINES: How long did this go on?

BRUCE: The break down lasted for several days, perhaps a week. My captors pumped some kind of gas into the room which put me to sleep. They would do this from time to time— typically when something in my room needed to be fixed or changed. While I was under, someone came in and cleaned my room. I had thrown my food around the room like an ape. But someone cleaned my room, gave me new towels, scrubbed the walls. I was given a set of pajamas then, and a new set of clothes. I woke very sick, but the gas had successfully calmed me down.

GAINES: And that brought you back?

BRUCE: There was a moment around then, while I was in laying bed, still sick from the gas, when I heard the music for the first time.

GAINES: What do you mean?

BRUCE: When I say, “I heard the music,” I mean I realized that I preferred one song over the others. That was the breakthrough. I did not despise every song on the album equally. I admitted to myself that I had a favorite song. This song was not as vile as the others. I preferred it to the others. I was relieved when it came on.

GAINES: And that song was?

BRUCE: For three years, to myself, I called it “Tears Gone Cold,” although I now know the title of the song is “Stan.” The name I gave it was based on a poor hearing of the lyrics, which are sung by a woman whose name I now know is Dido. The actual lyrics are “tea’s gone cold.”

GAINES: Did you have a different name for the woman who sung those lyrics?

BRUCE: In my mind, I called her “Tears Gone Cold,” as well. So “Tears Gone Cold” was the name of the woman and the song. There is one other place in the boy’s music where women can be heard, though they’re only moaning and cooing. “Stan” is the one song wherein a woman sings. At first, I merely liked “Stan” better than the other songs because of Tears Gone Cold’s voice, but gradually her voice came to signify something else to me. Her voice redeemed the whole song, and then the song redeemed the whole album, then the album redeemed my life.

GAINES: Did you have a name for Eminem other than “Eminem”?

BRUCE: I had many names for him. There were also ways that I thought of him which are beyond words.

GAINES: What other names did you have for Eminem?

BRUCE: At some point early on, I figured out that his name was Marshall Mathers. Two M’s. MM. Eminem. I still remember the moment I figured out how he had chosen his nom de plume. I thought of him as “Marshall,” sometimes. I also called him “boy” or “the boy.” Later I called him “my boy.”

GAINES: How did the record “redeem your life”? Why was it so important to realize you liked one song more than another?

BRUCE: It confirmed to me that God was with me. Within Christian metaphysics, there is really no such thing as “the power of evil.” God is existence, but evil is non-existence. Evil is an absence, a nothingness, a cancer. There is no ability to do evil, but an inability to do good. Consequently, inasmuch as something exists, it is good. All things which exist reveal the goodness of God, even if some very evil things reveal that goodness in a warped way.

GAINES: So, The Marshall Mathers LP is a little good?

BRUCE: If you have the option of listening to Mozart’s Requiem, listening to Eminem would be a waste of time. If you have the option of silence or Eminem, Eminem is still a waste of time. But Eminem is better than non-existence. Eminem is much, much better than Hell. Eminem is infinitely better than pure, unadulterated evil. There was nothing about Eminem I liked, at first. But when I had reached a point of complete loneliness, the voice of Tears Gone Cold cut across the loneliness with something like a divine eminence. When that woman sang, she filled the whole universe. When she sang, her voice could be heard beyond the reaches of this galaxy. You see, at all times and in all places, God fills all things. And so, if God is with me, and if I am hearing Tears Gone Cold, then God is hearing Tears Gone Cold within me and simultaneously filling the outer reaches of the cosmos. The beauty of that woman’s voice became the sacrament of God’s omnipresence. Reality was suspended by a string over a swarming sea of chaos, and Tears Gone Cold’s voice was the only thing which kept reality itself from plummeting into incomprehension and material inevitability. Her voice surprised me every time I heard it.

GAINES: What other songs from the record did you like?

BRUCE: I do not like any of the songs on the album. I should be clear about this. Nothing on the record gives me pleasure. No one enjoys going to confession. The boy is quite sad, quite morose, willingly self-destructive, obscene, though I love the album. And I love the boy. I pray for him constantly. “Stan” was the song that taught me to love the boy, but there’s nothing about the album which is pleasant.

GAINES: A moment ago, you mentioned some theological reflections which helped you come to terms with the album, but why do you love the album?

BRUCE: Until I came to love the boy, the music bothered me. My hatred for Eminem grew and grew until I broke down. In that break down, God gave me over to my own hatred, though He had graciously shielded me from my hatred until that point. But when I came to love the boy, I was able to think of God again, my wife, my studies. I was able to think again.

GAINES: So, love was a self-defense mechanism? You loved Eminem so you could think clearly again?

BRUCE: My desire was not to think clearly. Rather, I came to love Marshall because he was a human being. This sounds horribly cliché, I know. I once encountered a quote from someone, I cannot remember who, though it might have been Marina Abramović, who said that if you stare at any human face for long enough, you will begin to weep. The whole cosmos is imprinted on each human face, and as some aphorist once said, “the voice is a second face.” The human face is contained within the human voice, though it is buried quite deep. We are embarrassed when people we admire hear us sing for the first time, but this is true for the same reason that thieves wear masks. A man’s voice makes him known. If you listen to a man’s voice for long enough, you will see his face. Every human face is constantly turning into every other human face, even while it remains the same. Listening to the boy all day every day was primarily a lesson about human faces.

GAINES: Have you listened to the album since you were set free?

BRUCE: Yes.

GAINES: Does it sound different now that you do not have to listen to it?

BRUCE: I did not have to listen to it while I was incarcerated. I realized this about a year into my stay. There was a very sharp edge on the corner of a dresser in my room, and I realized one day that with a sudden, violent motion, I could smash my windpipe into the corner and end my life. From that point on, listening to the boy’s music was entirely voluntary.

GAINES: You don’t still listen to the album constantly, do you?

BRUCE: No.

GAINES: Why, then?

BRUCE: There is an interesting story in Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search For Meaning which I have thought about often since my release. Frankl was a Jewish man who survived several years in a concentration camp and went on to found a school of psychotherapy which I admire very much. Regardless, at one point during his time in the camp, Frankl visited a Jewish woman who was sick and confined to a bed. She was dying. There was a window in her room through which the woman could see a tree, a single tree. She could not see the entire tree, but only a branch. There was nothing else in the room to look at, and she was all alone for most of the day, so she looked at the tree. She told Frankl that she spoke to the tree and the tree spoke back. Frankl asked her what the tree said. The girl said, “The tree says, ‘I am here. I am here. I am life, eternal life.’”

GAINES: Why do you believe someone locked you away for three years just to have you listen to The Marshall Mathers LP?

BRUCE: I have asked myself that many times. Whoever captured me went to great expense to prove to me that I was not being tortured. I ate so well. I did not live in squalor. I suspect that many other people were being held alongside me, in nearby rooms, though I never saw them. At a certain point, I became convinced there were two human souls just beyond the wall beside my dresser. I would sometimes place my hand on the wall and I could feel the faces of those two souls. One was a woman, but I could never tell about the other. But I was in some sort of black-market prison. There was no television in my room, nothing to write with. I was left entirely alone with the music. Someone wanted me to listen to this music.

GAINES: Who?

BRUCE: Someone who was convinced that doing so would be good for my soul.

GAINES: Was it good for your soul?

BRUCE: Yes.

GAINES: How so?

BRUCE: Before my incarceration, I was a very angry man. I was angry for a long time. When I thought of hell, I was pleased. I was pleased because I did not fear hell, though I knew others should. All I ever thought about was justice. Justice was the purpose of the world. So far as I was concerned, before my incarceration that is, there was really no human being viler or more unlovely than the boy— or people like the boy. He was an icon for everything I hated. After my incarceration, I am more convinced than ever that the world is an evil place— or, that “the days are evil,” as St. Paul says. However, I now understand that I am the evil of this world. The world needs to be saved from people like me.

GAINES: Does the world need to be saved from people like Eminem, as well?

BRUCE: I am not concerned with the evil of people like Eminem. So far as I am concerned, there is no difference between the boy and myself. About half-way through my incarceration, I began praying every lyric on The Marshall Mathers LP. All the lyrics were a confession of my own sin. There was no sin the boy had committed which I had not committed in thought, word, or deed. All his hatred and loathing of the world was my own. When we confess our sins, we ought to confess the evil things we have done— and yet, my own sin was so great, confessing a discrete list of actions seemed too small. I did not want to confess a list of things I had done. I wanted to confess my whole life. I wanted to confess my whole being to God. The boy’s music became my life. The boy was miserable, I was miserable, and so when I sang along to the music, I gave myself to God in the boy’s words.

GAINES: Have you spoken to Eminem since your release?

BRUCE: I pray for his soul every minute of every day, but no, I have not spoken to him.

GAINES: Would you like to?

BRUCE: I’ve come to know the boy on such a profound level, I don’t know that it would be fair to him if we met. I would not want to embarrass him.

GAINES: I think it’s safe to say you’re the only middle-age theology professor in the world who knows all the lyrics to The Marshall Mathers LP.

BRUCE: That is probably true.

GAINES: Would you like to meet the woman you now know is named “Dido”? What if a meeting could be arranged?

BRUCE: That is another matter. Just a few days after my incarceration ended, I enrolled my name to become a member of the Roman Catholic Church. I was officially received into the Catholic Church two months ago now. Prior to my incarceration, I had, of course, argued with a great many of my Catholic colleagues over the years about various doctrines, but especially doctrines pertaining to Mary. Many of these arguments turned on the concept of a relationship between femininity and ecclesiology which they saw, but I didn’t. None of the arguments my Catholic colleagues made about this relationship made sense to me until the female voice— the female face, really— was presented to me as pure respite from the horrors of my confession. The small portion of “Stan” that Tears Gone Cold sings was the one part of The Marshall Mathers LP which I never confessed as my own sin. Her voice is and is not part of the record. I always understood her part on the record as the consoling response of the Church to my confession. I know how strange all of this sounds, but from the depths of extreme isolation and loneliness, the meaning of everything— the meaning of each individual thing that you can see and hear and taste, the meaning of everything you remember and everything you know by heart— it all begins to grow outward. Nothing you can see strikes you as ordinary. Every little thing is hiding something more important and loneliness brings those hidden things to the surface. The more isolated you are, the less isolated anything else seems. All things seem connected. You begin to interpret everything the way that St. Gregory of Nyssa interpreted the life of Moses. Loneliness is the battery that charges meaning. All meaning derives from the fact that a simple God, a God without parts, created and sustains all things. Extreme loneliness puts a man in touch with the simplicity that binds all things together.

GAINES: I will admit I know very little about Christian theology, but you strike me as a man who has a fairly mystical view of the world.

BRUCE: That’s fair. I wasn’t always that way.

GAINES: Would you say that the cumulative effect of your incarceration has been good?

BRUCE: It saved my life.

GAINES: In that case, who do you believe is responsible for your incarceration?

BRUCE: I should tell you that I have no recollection at all of a “man with a green flight jacket,” this figure Jim [James Cochrane] claims he saw and which someone at Chez Monique claims they saw, as well. The last thing I remember from October 17th is eating a candy bar in my kitchen while I listened to NPR on a radio we used to keep next to the microwave. I don’t remember a black BMW. I still have the clothes they dressed me in when I was released— these outrageously expensive French clothes— though I have no recollection of putting them on. Someone told me the white jacket I was dressed in when I woke up at Chez Monique retails for two thousand dollars. Who does such a thing? I have a few ideas, but they are, as you say, “fairly mystical.”

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.