How Christians Invented Secularism (And Pop Culture)

The end of the year calls us to take up, once again, our traditional positions on a whole host of arguments about holidays, holy days, and the calendar. When is the proper time to begin listening to Christmas music? Is Black Friday shopping demoralizing and degrading? Has Christmas become overly commercial? Was Jesus Christ actually born on December 25th? Was Christmas simply a Christian attempt to co-opt Saturnalia? Is there really a war on Christmas? We bicker with one another about fairly trite matters during the rest of the year (politics, civics), and yet, for my money, one of the greatest of the annual Christmas miracles is the arrival of a whole season in which we properly devote ourselves to worthwhile arguments.

Over the last twenty years, we have begun debating whether “Happy holidays” is an appropriate greeting come November, or whether “Happy holidays” is an insult to the particularity of Christmas as a Christian holiday. When Margaret the Target cashier tells you, “Happy holidays,” has she insulted Jesus Christ? Is “Happy holidays” a sad capitulation to the zeitgeist, which demands Christ not be named publicly? In the midst of asking such questions, Christians often complain of the slow, though constant encroachment of secularist values upon the American public square over the last so-many years. Such complaints betray a belief, common among contemporary Christians, that secularism is opposed to Christianity, and that Christians and secularists are caught in some kind of turf battle. However, a cursory investigation of modern history quickly reveals that, in fact, secularism was never inflicted upon the western church from the outside. The church’s first recognition of secularism was not as an enemy, but a savior. Secularism was originally conceived of by Christians for Christians.

In The Oxford History of Christianity, editor John McManners comments on broad shifts within Christian thought and practice between 1600 and 1800:

Religion was on its way to becoming a matter of intense personal decision: if there was a single message and driving force behind Reformation and Counter-Reformation, it was this. Secularization was the inevitable counterpart… The idea of Christianity as some huge galleon blown on to the rocks then pounded by the seas and plundered by coastal predators in an age of reason and materialism is mistaken… European life was being secularized; religion was becoming personalized, individualized: the two things went together, and were interdependent.

Throughout the 16th and early 17th centuries, Christian denominations proliferated, but not within the same cities. Rather, one found Lutheran cities, Catholic cities, and Calvinist cities, but one could not readily expect to encounter— within a single city— a Lutheran church, a Catholic church, and a Calvinist church all in a row. Turf battles were common, entire cities sometimes converted en masse. By the 18th century, however, many Christians were coming around to the economic advantages of trade with rival denominations. The most pluralistic and tolerant nation in the early modern era, and thus one of the richest, was Holland. McManners quotes an English Quaker, reflecting on the religious toleration offered in Holland during the 17th century, “It is the union of interests and not of opinions that gives peace to kingdoms.” An English diplomat to Holland remarked of the place, “Religion may possibly do more good in other places, but it does less harm here.” In other words, religious unity has a unique power to bind people together, but religious unity is increasingly rare; religious difference has a unique power to tear people apart and anger them, and religious difference is quite common. In setting religion aside, a community volunteered to go without certain civic benefits— a shared sense of purpose, say, in a citywide fast from meat during Lent. However, pluralism offered Catholics the economic benefit of being able to sell meat to their Protestant neighbors during Lent, even while Catholic neighbors abstained. Religion was less and less a thing of cities, but a thing of households.

When I speak of “setting religion aside,” I simply mean consigning religious conversations to the home, as well as all forms of piety, festival, habit, worship, and practice, ultimately to avoid religious argument and dispute. During the 17th and 18th centuries, religion was increasingly regarded as a dangerous and volatile thing with a tendency to disrupt public peace. Like a disease, religion was to be quarantined in the home, where, bereft of public function, worship and doctrine would increasingly become a matter of taste and preference, subject entirely to the individual strength of a particular family, unsupported and unconfirmed by the broader community. Religion was not violently ousted from the public square, but willingly retired. Christians simply came to the tacit agreement not to talk of religious things in public, and to not evidence the distinctives of their tradition in the presence of other traditions. To this day, Catholics and Protestants can be friends, of course, but a great many of these friendships depend on both parties maintaining an unspoken agreement to not talk about certain things. One can imagine the scandal which would rip through a classical Christian school if the principal staged a lunch hour debate, performed for the students, between the Catholic history teacher and the Presbyterian literature teacher about the matter of purgatory or transubstantiation.

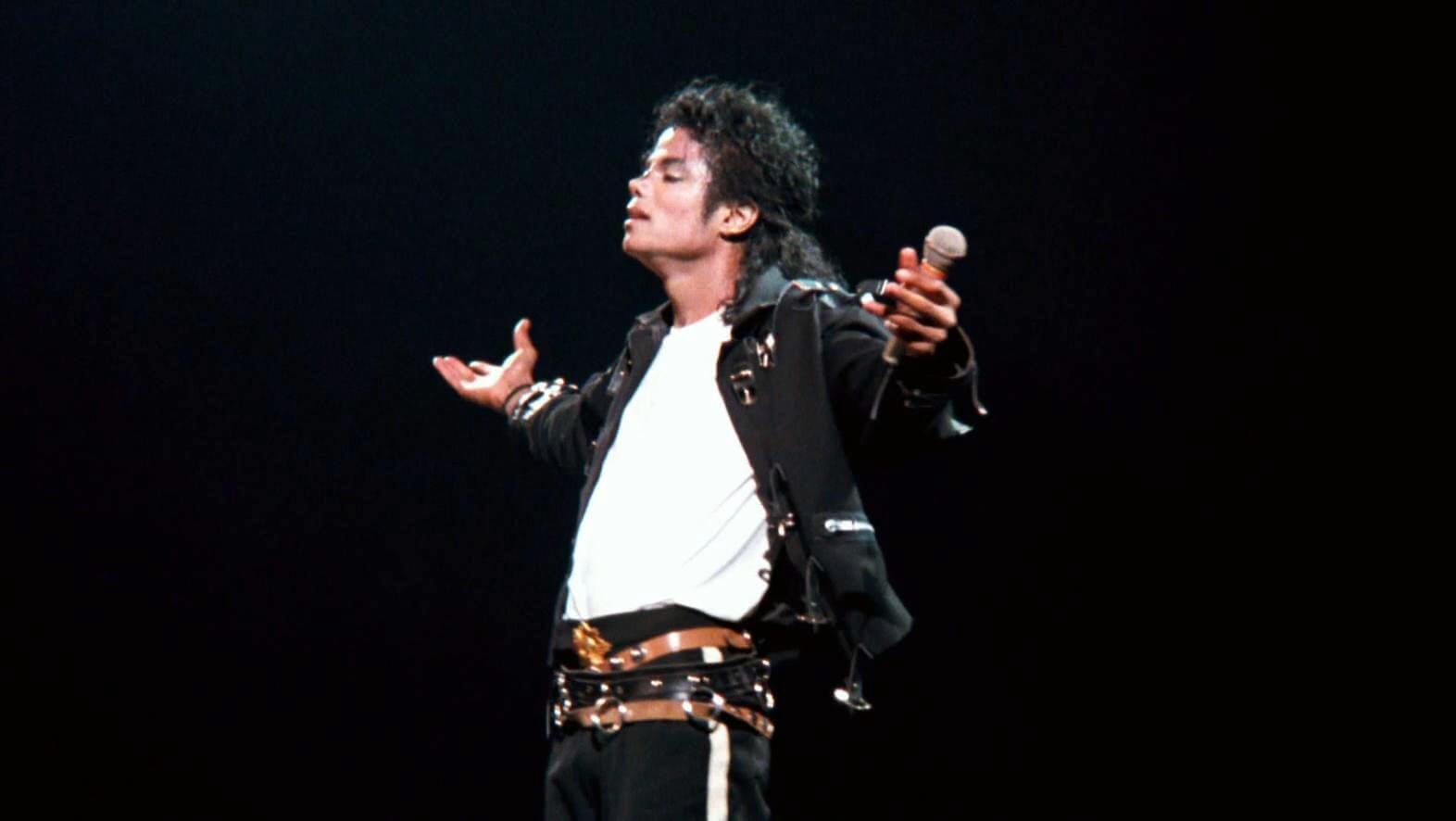

Of course, a religion-less public square entailed the need for a new kind of culture, a culture which could cut across denominational lines. Lutheran music was out, Catholic music was out, Calvinist music was out. What the 18th century West needed was books and music emptied of creedal value, liturgical purpose, or traditional forms; what the west needed was pop culture. Dante and Josquin des Prez were out. Bronte and Debussy were in. Popular culture is simply an artistic expression of religious anxiety and secularist impulses. The greatest pop culture artifacts, like Star Wars or Michael Jackson’s Dangerous, say, confess no creed and recite no catechism. We might argue they are “merely human,” yet their vision of “humanity” is entirely devoid of any local or particular loyalties. Star Wars can only be “merely human” if it is not-Catholic or not-Presbyterian, a lesson which subtly teaches Catholics that Catholicism is not a fulfillment of human nature, but superfluous and ultimately unnecessary. A lifelong diet of popular culture cannot fail to inculcate a deep skepticism toward the idea that denominational particularities deserve our unreserved attention and affection. Pop culture teaches the Presbyterian that Christianity is one thing, Presbyterianism another, and thus the Presbyterian church is unneeded, nonessential, and lucky to have any parishioners at all. Pop culture teaches the Presbyterian that no church is genuinely human, but that humanity— whatever real humanity is— lays outside the bounds of any confession. Confessions are inhuman, much like oaths and vows, as the Romantics taught.

I am eager to not be misunderstood: I am all for “Merry Christmas.” However, a strong insistence on “Merry Christmas” (and not “Happy holidays”) is a dare that religious difference need not be as divisive as we think. “Merry Christmas” is a confidence that Catholics can be strongly Catholic in front of their Presbyterian friends, and that Presbyterians can be very Presbyterian in front of their Catholic friends, and that the performance of our respective traditions is safe. “Happy holidays” is not so much secularism as it lowest common-denominator Christianity, the kind of Christianity which falls to pieces in the face of committed, zealous secularism, the kind which has currently set American universities on fire. At the same time, zeal makes genuine diplomacy possible. Wishy-washy people from different churches and different nations invariably seek one another out, not to hammer out hard-won agreements, not to dialogue, but to praise one another for their open-mindedness and leniency.

The return of “Merry Christmas” calls for all traditions of Christianity to be less squeamish, less touchy, and less easily offended— not because we care less for our creeds and dogmas, but because we care more, and the price a Catholic man pays for being very Catholic in public is permitting his Presbyterian neighbors to be very Presbyterian in public. This will mean going back to our churches and learning what it actually means to be Presbyterian or Catholic (because we do not know and must confess the sin of not really caring). We must do this with the confidence that our churches are also teaching us how to be truly human, not superfluously “religious.” This will mean submission, yielding, listening and not speaking. This will mean few of us are truly ready for “Merry Christmas.”

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.