Hell, Locked From The Inside…Paradise, An Acquired Taste

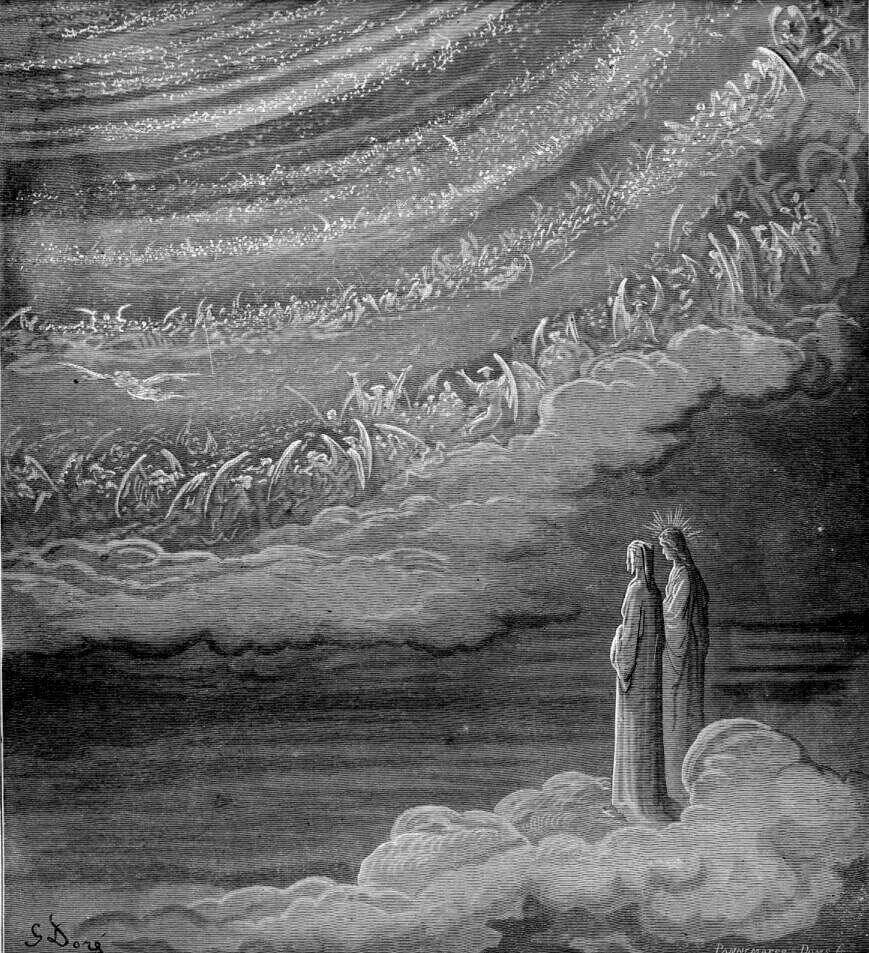

Is Hell locked from the inside? Dante seems to think so. Few residents of the Inferno object. From time to time they pitch a sob story, but none of them has a sense of the infinite, and so they don’t know how to long for something better. For the last several weeks, my Medieval history class has bantered back and forth various arguments in favor of Hell being locked from the inside or from the out. It is easy to take simple comfort in the notion that Hell is locked from the inside; in such a scenario, the only persons who go to Hell are those who truly prefer Hell to Heaven. Obviously, Hell is awful. Should we not expect that very few persons will ultimately brave the broad way which leads to destruction?

At the same time, the notion that Hell is locked from the inside is counterbalanced with the notion that the only persons who go to Heaven are those who truly want to go to Heaven. It might be a bit too easy to say that everyone wants to go to Heaven. In the closing chapter of The Problem of Pain, CS Lewis suggests that “the joys of Heaven are for most of us, in our present condition, [would indeed be] “an acquired taste” – and certain ways of life may render the taste impossible of acquisition.” In other words, were we aware now of what Heaven is about, few of us would be intrigued. Holy Week is a fine testament to this claim; when Heaven lived among us, we wanted a warrior on a white steed who would deliver a simple, easy and Carolingian empire of cultural superiority and power. Christ was the rabbi could raise the dead, the final war weapon for which the righteous waited; the Romans could not stand a chance against such a one, and on the weekend of Pascha, when the Holy City was packed with the pious, Jesus road in on a donkey, much like Judas Maccabeus two centuries earlier. Jerusalem would soon be reclaimed, Rome ousted.

The kingdom of heaven ended up being little of what we expected, though; the Crucifixion and the Transfiguration were parallel events, to our continual consternation, and the long haul of history has proven that even that Late Antique confidence that Rome was God’s special city, His special empire, and that Christendom would spread over the earth like Noah’s Deluge, were proved pipe dreams.

The heaven we want is not often worth wanting, though.

Lewis’ suggestion that heaven would like be “an acquired taste” is set on edge when thinking of the persons in Dante’s Inferno, who all continually terrify and torture themselves. If anything is an acquired taste, certainly self-mutilation meets every qualification imposed by the term. We start small, cutting deep enough to draw blood, wincing and crying all the while, and perhaps after years and years of practice, we’ve become malicious gossips, closet gluttons, seducers of mirrors, porn addicts and all manner of habits have been adopted which are no pleasure, unenjoyable to the nth degree, and yet we’ve become habituated to them. Plenty of ostensibly good people are dangerously cultivating a taste for Hell now; Lewis suggests “certain ways of life may render the taste impossible of acquisition,” and I much doubt those “certain ways” are limited to, say, murder and kidnapping alone.

The whole concept of “an acquired taste” is transformed when we think of righteousness, though. Developing a taste for Hell is one of blunting and benumbing, although developing a taste for something good is altogether different. What exactly is “an acquired taste”? Perhaps nothing more than the whole person trumping the self. The self— that small, constricted, truncated, edited image of our whole person— declares itself opposed to something, and the wisdom of whole person revolts. The self says it does not like wine, tomatoes, George Herbert, Tim Hecker, thyme, Brutalist architecture… but the whole person sees that something of mysterious worth and indeterminate goodness is ineffably coiled up within the taste, the sound, the rhythm, and so the whole person begins to insinuate the self in a project of expansion until the self comes to love the desired thing.

The process of acquiring a taste is far more intuitive, practical and simple than we might credit it, though. Say a man who hates tomatoes marries a woman who love tomatoes; he resolves to acquire a taste for tomatoes. Should he eat nothing but tomatoes for a week, gagging down every unsalted, unprepared bite? Likely, such a course of action would result in the revulsion of the stomach, not to mention bitterness of heart and loss of health. Perhaps he should start with a Caprese salad, wherein the acidity of the tomatoes is tempered by the wildness of basil, the mildness of fresh mozzarella, the prudent, thick maturity of olive oil and the spirituality of salt. Perhaps he should start with a tomato soup, employed as a sauce on the sharp tip of a diagonally-cut grilled Gruyère de Comté. Perhaps such a man should study the tomato and come to know its biological properties, the country which first cultivated it for food, the nutritional effects of drying a tomato in the sun. The man might learn the varieties of tomatoes— which ones are sweet like berries, tart like lemons, clean like cucumbers. Images of tomatoes are studied, and the range of color and sheen is taxonomied. A photograph of a tomato is placed on the car dashboard, the refrigerator. The man might learn the difference between crushed tomatoes in a stew and chopped tomatoes in a chili, how either plays on the palate differently. The man might grow his own tomatoes, just a few, and eat them before they are ripe just to experience the unique disappointment of the impatient gardener. In all this work, the tomato comes to mean something different to the man; before, the tomato was undesirable because of the taste, because of a sensual disagreement. After belaboring the tomato, the taste has not changed, but the meaning of the taste has changed. When the man hated tomatoes, yet they were acidic and seemingly incapable of committing between sweet and savory; after so many months of study and a steady, careful exposure, that lack of commitment has become a charming ambiguity. This or that species of tomato registers particularly within a spectrum of flavor, and the same Beefsteak tomato purchased at a supermarket months earlier is enjoyed according to shifting, enjoyably disputable standards. What is essential about this work, though, is that the tomato has stayed the same. The man has changed. The man has acquired the taste.

How to acquire a taste for heaven, then? The task seems daunting. How to acquire a taste for Church? For the things of Church and the things of God? How to eat the Eucharist without a sense of terror that this very food is the only food of eternity? That the Last Supper is the Final Supper, the Eternal Supper, the only Supper? The Supper is an acquired taste. Through the senses, and the deprivation of the senses— not to mention the intellect, intuition and imagination— we have been given a panoply of tools with which to slowly and methodically acclimatize ourselves to a taste for heaven. The labor of learning to want to go to heaven requires nothing less of the will, or of method, than learning to love the tomato, or liquor, or dissonant music.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.