The Ghetto, the Monastery, and the Classical Christian School

What the "Benedict Option" might look like for the Classical Educator

It is, probably, the most barbed of the criticisms leveled against the whole array of classical, Christian, and homeschooling endeavors. Yet it shoots forth from the secular media, the mainstream Christians, and our own self-doubts—the declaration that our homes and schools are too heavenly minded to accomplish any earthly good; that we have absconded from the essential work of evangelizing or redeeming culture; that our communities are merely “Christian ghettos,” as morally irresponsible as the monasteries of the Middle Ages.

But once those of us in the “ghetto” reach that comparison, we likely recognize its fallacy. As we have learned, we owe the medieval monks our thanks for whatever literacy, medicine, art, theology, philosophy, and textual transcription have reached us from those supposedly dark ages. “Ghetto” may be a pejorative term, yet it differs markedly from “monastery.” Which one we are might be open to debate, but confusing the two betrays a lack in understanding of both history and Christianity’s cultural situation.

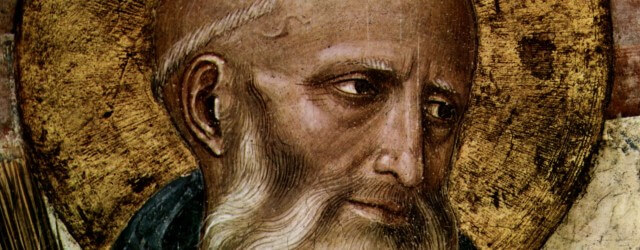

And so arises the recent flurry of conversation about “the Benedict Option,” a term coined by Rod Dreher to describe an old-new paradigm of Christians’ stance in culture. Mr. Dreher (who, incidentally, spoke at the CiRCE conference last week) has written about the Benedict Option for years, but a recent piece for TIME propelled the discussion into media, coffee shop, and dinner table conversations.

A full picture of the Benedict Option must, at this point, be pieced together from the many blog posts and comments devoted to it—Dreher’s interviews with Eric Metaxes (here and here) provide a good introduction, as does the historical reference to St. Benedict’s establishment of early monastic communities. To borrow Dreher’s own words, “It’s my name for an inchoate phenomenon in which Christians adopt a more consciously countercultural stance towards our post-Christian mainstream culture.” Or, perhaps a bit more fully, it seems to me that the Benedict Option describes a purposeful retreat (by individuals, families, schools, churches) from participation in aspects of modern culture in order to preserve and extend the age-old tradition of a Christian culture that sustains the faithful, nurtures their children, and—precisely because it stands apart from the world—welcomes the world as guest. And also, that Christians regard this cultural abstention and formation as a more potently transformative tool than is political action—though that does not at all mean they withdraw from political action.

But what does this actually mean? That question defies a pat answer, for as Dreher explains, “We are going to have to be experimental, because we have never faced a post-Christian culture. The first point is for Christians to wake up and face reality. There will be no ‘take back our country’ moment, because we have lost, and lost decisively. We are rapidly de-Christianizing.” Thus, the Benedict Option means recognizing that Christian faith and practice will no longer be inculcated in our children, let alone our neighbors, by the surrounding culture; that, to the contrary, cultural products will invariably undermine Christian faith and practice; and that it is a waste of effort to try to whip the culture back into Christian shape. It means, then, that Christians will dramatically diminish their consumption of popular culture and focus instead on exploring their heritage of Christian culture and finding fresh ways to embody it—in music, art, lifestyles, words, habits. It means that they will do this whatever the political climate and their representation in it happen to be. It means, in sum, that the particulars of the Benedict Option are the old monastic principles of Order, Stability, Discipline, Community, and Hospitality set within creedal Christianity. Quoth Dreher:

It should go without saying that a method for living out these principles is going to look very different for lay people living in the world than for vowed religious living in single-sex communities behind monastery walls. I think whatever forms the Benedict Option takes, we have to understand that it’s going to be diverse, depending on local needs, and particular religious traditions. How Catholics live it out won’t look exactly like how Southern Baptists live it out. How urban Christians live it out won’t look exactly like how rural Christians live it out. The ultimate goal, though, is developing communities that can be islands of stability, sanity, and goodness in a fast-moving and chaotic culture that works against all of those things.

Criticisms and counterarguments surrounding the Benedict Option can be discovered in the comments to any of Dreher’s recent posts. Here, however, perhaps a different conversation could begin. Rather than testing out Dreher’s proposal by analyzing it in the abstract, as most of the blog comments do, might we not hammer it on the anvil of actual practice? Christian schools and homeschools are, as Dreher affirms, close kin to the kinds of communities he advocates. So we might ask—what are some practical ways in which a conscious embrace of the Benedict Option might influence our actions? Would these be viable/healthful? Do they give us confidence that the Benedict Option might succeed?

The following is a (very) initial list of ideas for applying the Benedict Option in real schools/home schools. It can be extended and examined in the comments:

- Talking as much about virtues and faithful habits as we do about skills and truthful knowledge

- Shaping students as creators rather than consumers by giving them opportunities to make music, art, literature, and media, in addition to the more typical classical focus on analyzing these things

- Practicing regular and special fasting in our own lives—from food, but also from the radio, or iTunes, or NetFlix, or smartphones, or Internet

- Challenging our students to join our fasts

- Avoiding the temptations to make class material “relevant” by frequent analogies to pop culture

- Celebrating church holidays in the classroom—not just Christmas and Easter, but Advent and Lent, Pentecost and Epiphany

- Facilitating students’ bonds with their local churches. For example, could a Rhetoric class do a project exploring the concept of audience by interviewing a spread of church members to discern what they count as persuasion?

- Presenting the stories of great Christians who have preceded us in the study of math, science, literature, music, philosophy—not to mention missions, politics, business—to fill the human need for heroes, which pop culture stuffs with celebrities

- Making a strong effort to invite “post-Christian” community members to participate in events in the life of the school, and so to taste the foreign, joyful confidence of the faithful life

Do these ideas seem resonant with the Benedict Option? Could they be refined or added to? Do they differ from or redirect what we are currently doing? Do they shine any new sort of hope into an unsettlingly foggy future?

Lindsey Brigham Knott

Lindsey Knott relishes the chance to learn literature, composition, rhetoric, and logic alongside her students at a classical school in her North Florida hometown. She and her husband Alex keep a home filled with books, instruments, and good company.