Getting Through To Teenage Slackers

I was a bad student. Starting my freshman year, I attended a classical Christian school. By senior year, I was sneaking down to the local pizza parlor during lunch to smoke cigarettes and watch music videos. I never aimed to do well, only to pass. If my Biology grade was running a 77, that meant I had 7 points to spend on slacking off before the semester ended. I was a teenage sloth.

As a hard-slacking teenage boy, I was nonetheless well-spoken, which meant adults frequently offered me exhortations which began, “You’re very smart, but you could be accomplishing so much more…” Despite coming from the best of intentions, this advice was terrible for my soul. When an adult says such things, this is what the teenage slacker hears:

Unless you want to become very rich, you can keep slacking off. Your current level of effort will be sufficient for a normal life. You are sufficiently smart that, without really trying, you’ll end up with a $50,000 a year job. People who are less intelligent than you will have to struggle to get $50k a year, but you will not. If you worked very hard, you could be making $150,000, though you are not an ambitious person and are probably content with the prospect of a normal future. As such, continue slacking off. You should expect to be just fine.

Most adults, even good Christian ones who love children, are still prone to advise teenagers in the quasi-therapeutic language of advancement, encouragement, and optimism which they have learned from public service announcements. Such language is always bereft of dire consequences, offers only nebulous warnings (“things won’t go so well in college”), and assumes hidden resources of human goodness and resolve which, even as an Orthodox Christian, I find dubious. Teenagers quickly figure out that this language is spoken by adults who either don’t have a high enough pay grade to royally chew them out or adults who still suffer from enough residual guilt for their own sins they don’t feel it fair to actually lay down the law for others. Teenagers have a miraculous capacity to tune out such language, and most teens are willing to nod for a few minutes, make appropriately contrite sounds, and white knuckle it until everything which comes after, “You’re very smart, but…” has finished for this go round.

One of the only chastisements I ever received which has truly stayed with me came when I was 20, leaving the house dressed in clothes I pulled off the floor, and my father, who never cursed, said to me, “Josh, if you want a girlfriend, you have to look like you give a damn.” He cut suddenly through all the red tape of politeness and positivity and struck me where I was lonely. On the rare occasion I get through to a young slacker, I have appealed to the same unsavory possibility of eternal bachelorhood. The kind of rebuke which is chiefly concerned with “not breaking a bruised reed” is rarely a genuine rebuke, though, and attempts to begin a gentle convalescence before any dangerous, painful operation has truly been undertaken. In college, I sat under many positive, encouraging teachers. My recollection of their instruction is hazy and indeterminate, though I recall with startling and productive clarity the two lit teachers who were ever blunt and honest in workshops.

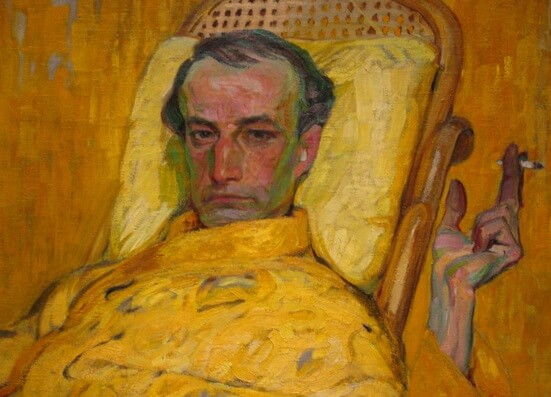

At the same time, presenting myself as some kind of “former slacker” always carries the risible possibility of insinuating I have become a good person. While I have learned better manners and acquired better tastes, at 35, I am still trying to dig myself out of the pit I fell in when I was a teenager. A man’s habits at 16 become his habits at 17, which become his habits at 18 and 19… I have been confessing the same sins for years, become more subtle in how I vindicate myself, and negotiated more sophisticated treaties with pleasure, but I am the same old me. If there is an argument to be made that I have changed, I would need someone else to do it. Of course, had someone showed the hard-slacking Gibbs in high school a photo of Gibbs in adulthood, standing beside pretty wife and funny children, I would have said, “I knew it! I knew I would turn out okay.” The slacker is, of course, overly concerned with appearances and material conveniences and does not like getting to the heart of the matter. What the 16-year-old Gibbs needed to see was the adult Gibbs weeping to his priest, at confession, “I do not struggle with temptation. I lay down for temptation like an obedient dog.”

Obviosuly, I know more now than I did at 18, but knowledge alone will not change a man. Right knowledge must be joined with right desire. When a slacker is told, “You’re very smart,” he is apt to hear this as the most important part of the equation, as though everything besides “You’re very smart” is surplus, fat. When he hears, “You’re very smart,” a slacker recalls all that he has gotten away with, all that has escaped the notice of the adults, all the excuses which have (miraculously) flown, all the money no one has ever missed. The way to the heart of the slacker is not through a kind, gentle insistence that his amazing intelligence just needs to find a good work ethic. The slacker has made many promises to himself about how he will work hard “when it counts” in the future, and repeating “You’re very smart…” to the slacker confirms his supicion that he can simply flip the adult switch when the time comes. If it is “not too late” to begin working hard and caring at seventeen, then neither is nineteen or twenty too late.

So what do slackers need to hear? If I could dial back through time, I would tell my hard-slacking sixteen-year-old self, “Your fears are justified. You’re not smart enough to make it on smarts alone.” Merciless reason (from a merciful God) besets the heart of the slacker, who wants something for nothing, but secretly admits to himself that his desires are unlikely. The slacker is often cultivating a contempt for the world, as well, which is necessary because he knows he is competing against the world for success in the future; the more contemptuous and stupid the world, the more likely the slacker’s innate knowledge is to slide him into a normal life. However, while the slacker will always have stories of the world’s idiocy on hand to comfort himself in his laziness, he is anxious in his recognition that classmates are smarter and more charming than he is, and that his teachers have rarely evaluated him as rigorously as potential employers will. The slacker finds it hard to partake in the joy of his peers, for their joy is over their success, and their success is a sign against his own likelihood of success.

The slacker has also heard a few stories of respectable middle-class families (a cousin, someone from church) producing sons who have catastrophically failed at life, and from time to time, he stays awake at night wondering what exactly separates him from such possibilities. This uncertainty will keep a man sharp, and, if he ruminates on it long enough, send him off to do that other thing slackers so often neglect: pray for God’s mercy.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.