On The First Day Of Medieval History, I Play This Game

“How many wars is the United States currently involved in? One? Three? Nine? Would you be shocked to hear we’re involved in sixteen wars? Would you be shocked to hear we’re involved in two wars? Zero wars? If the United States went to war with Afghanistan tomorrow, would your plans for the weekend change? Maybe the United States is already at war with Afghanistan, though. Maybe we have been since before you were born. Or maybe the United States hasn’t technically been in a war in a long time, and we only do “police actions” now. On the other hand, who can say if that “technically” will mean much in the history books? Perhaps the fact that we don’t do “war” anymore will be lost to historians of the 22nd or 23rd century.

What is history when history is only history? What is history the history of?

There’s art history, which is the history of a discipline— painting and sculpture. There’s Renaissance history, which is a history of a time period— the Renaissance era. There’s American history, which is the history of a place.

I would submit to you that, often enough, when we think of history— just history— we think, “History of war.” History is the history of battles and generals and treaties and plunder. Is this fair?

And what deserves to “make history”?

“Big events,” we say. “Big events deserve to make history.” Events which change the most lives. Between two events— one which led to the death of dozens, and the other which led to the deaths of thousands— we count the second obviously more significant, more news-worthy, more history-worthy. Why? Because more deaths means more people are changed. More widows. More orphans. What changes more lives than death?

Perhaps laws change more lives. Perhaps history is a history of laws.

How many of you have ever illegally downloaded music off the internet? Most of you, I see. And you know there are laws against that? Is history the history of laws? Perhaps history is the history of obeyed laws, then. And how will we, as amateur historians, know which laws are obeyed?

I believe it is problematic to assume history is the history of laws because people break laws, and I believe it is problematic to assume history is the history of war because our lives don’t seem to change much according to the wars of our nation. We might be involved in sixteen wars, we might be involved in none— either way, your primary concerns have to do with tests, girls, food, getting caught, sports, punk records, youth group, and so forth. What changed your life more— the execution of Osama Bin Laden or the release of Star Wars: The Force Awakens? Which of these events did you talk about more? Think about more? Dream about more?

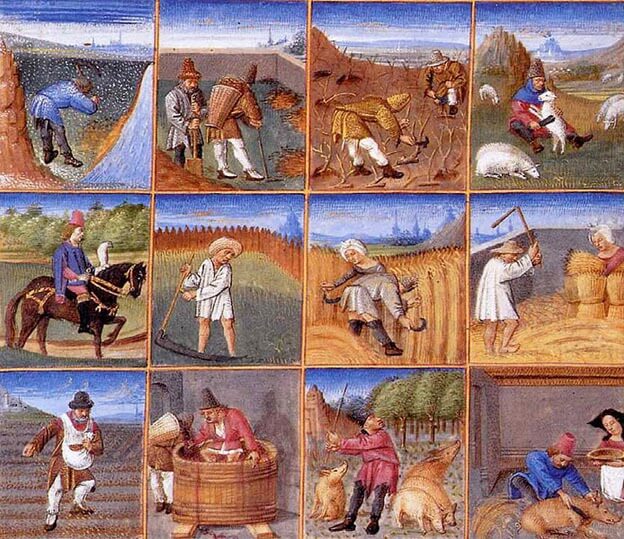

“War” doesn’t change your life much, and if you lived a thousand years ago, chances are good “war” wouldn’t have been high on your list of concerns back then either. You would have crops to worry about. Annual rainfall. Drought. Taxes.

Gentlemen, if you lived a thousand years ago, there’s a good chance that, by the time you were sixteen, you would have only seen a grand total of five girls. The average American simply sees a greater sum total of human beings in the average trip to the mall than the typical Medieval man saw over the course of his whole life. If everyone you know lives on a twenty-two acre plot of land, you live far away from pretty much everybody.

Fellows, consider this for a moment: if you’ve only ever seen five girls, they all probably looked drop dead gorgeous. If you’ve only seen five girls, they all probably looked like goddesses. Today, you compare the beauty of a girl in class with a hundred thousand other girls you’ve seen, including scores of girls who are famous only for their beauty. What if you’d only seen five girls? Who do you imagine is more blown away by the beauty of his wife— a guy who has a hundred thousand girls to compare her with, or a guy who has five girls to compare her with? Which of these two guys is more prone to dissatisfaction, anxiety?

I throw that question out there because when I think of history, I think of the history of you. History is the history of the self. All of history is a sacred text about the life of man. The bombing of Pearl Harbor is an historical event, but it’s also a timeless event about what a human being is. You study Pearl Harbor long enough and you’ll find it’s a parable. Everything is a parable and a prophecy. The longer I spend studying history, the more convinced I am that there is no “past.” History does not progress on a line. Instead, it deepens like a well. You learn about Pearl Harbor, Charlemagne, the age of Martyrs… the past gets closer and closer to you until you can’t really tell the difference between 1000 BC and yesterday. You learn about Charlemagne, you learn about yourself, your father, your children, the future. History is the human things, the eternal things, the always things, the omnipresent things. Charlemagne isn’t in the past. Charlemagne is in your blood. The study of Charlemagne isn’t the study of a man who was, it’s the study of a man who is. For the Christian, the past is above us, not below us. For the Christian, the past is not without us, the past is within us.

History is not the history of war only, or the history of law only. It is the history of those things, but that’s only a small part of it.

How can I prove to you that history is the history of present things, not past things? I have to start small. As small as I can.

If I could take you back in time a thousand years, I wouldn’t want to introduce you to someone famous, like a king or a pope or a bishop. I would want to introduce you to someone like yourself. An average man with an average life. I would want to sit you down with that fellow and let you talk to him for an hour, ask him whatever you like. If you had such an opportunity, what would you ask the one-thousand-year-old-version-of-you?

Now, you’re in luck, because that’s exactly what we’re going to do today. I have studied the Medieval Era long and hard enough that I can answer any question you might have as though I were a poor French onion farmer from the year 900 A.D. For the next hour, speak to me as though I come from eleven hundred years in the past. Ask me about religion. Sports. Hobbies. Girls. Politics. Drugs. Gardening. War. Call me Henry if that will make it easier for you to think of me as someone else.

Let’s get the easy and obvious questions out of the way up front. ‘What do you do for fun?’ is a question your kind always asks, but don’t be surprised if I ask for clarifications. What do you really want to know? Surely you care about more than my pastimes and hobbies. I don’t mind talking about those, but consider for a moment that you’ve got a genuine novelty from the past on your hands. Here’s a tip. Don’t speak to me like an abstraction. Speak to me like a person. Ask me about my children and whether I love them. Ask me to tell you why I love my children. Ask me about what disappoints me, what concerns me, what makes me nervous, what makes me elated with joy. Treat me like a person and you’ll learn more.”

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.

1 thought on “On The First Day Of Medieval History, I Play This Game”

What do you read to become an expert on the medieval period?