Finally, A Religious Star Wars Film

Please note: Spoilers ahead

JJ Abrams has good taste, but when it comes to matters of religion and spirituality, he has a tin ear. This was all deeply problematic when he was given the controls of the Star Wars franchise, for the Star Wars cosmos is deeply spiritual, and Abrams failed to understand the Force as anything other than a convenient way of moving furniture around.

In The Force Awakens, Abrams was occasionally able to invoke the Star Wars mood, for Abrams is a fine mood-maker. Cloverfield and Super 8 were zealously told adventures, however vapid both ultimately proved. Almost ten years later, all that really lingers of Cloverfield is an atmosphere. The characters were empty (you remember nothing about any of them, I swear), the monster emerged from nothing and returned to nothing in the end. Super 8 was a loving paean to Spielberg’s ET, but Abrams discerned none of that film’s universalism, occultist tendencies, warbled New Age philosophy, or even the rather obvious Cold War commentary. Abrams noticed suburban kids on bikes. While ET is a generously messianic figure, Abrams crafted a murderous monster which he nonetheless granted a Christological ascension in the closing moments of the film, and then had the killer baptize those who stood watching. Abrams is the kid whose hand shoots up whenever the teacher asks a question, and he always begins, “Yeah, it’s kinda like how…” even though it’s not actually kinda like that. As a non-practicing Jew, at best Abrams has a thin romantic’s interest in religion. Religion occasionally serves his artistic interests, but he offers no cult to the transcendent.

George Lucas, on the other hand, was as religious as it got back in the 1970s. Not Christian and not Buddhist and not Muslim, mind you, but religious. Lucas was the eager padawan of arch-religionist Joseph Campbell, the man who did more to form the modern religious sensibility than any other figure in the last hundred years. In a century of faltering interest in the spirit, Campbell made religion accessibly academic, but also comprehensible to the man of modest intellect. The blue collar worker of the 1950s and 1960s did not need an MDiv (in fact, it helped if he didn’t have one) to breeze through one of Campbell’s titles and walk away with a satisfyingly vague sense of the numinous any time he drove by a church, a graveyard, or even a statue of some long dead civic hero. Campbell loved gods and demons, angels and incense, and he knew gobs about it all and was willing to write on a ninth grade reading level. Star Wars became, of course, the narrative embodiment of Campbell’s love of gods and demons, angels and incense, prayer and meditation.

This is a film which bristles with religious energy.

This all leads me to the central point of this essay, which is the single moment in A New Hope which provides the mystery which charges the whole Star Wars universe with purpose: the martyrdom of Obi-Wan Kenobi. Ben’s willing death and subsequent physical annihilation into thin air constitute the most glorious moment of gnostic filmmaking in Hollywood history. As a Protestant child, few images granted me the sense of terror and comfort that accompanied Vader’s black boot impotently stamping Ben’s cloak— and while Vader has no real face, does he not depart from Ben’s empty clothing disturbed, baffled? Obi-wan had become nothing, but he lived nonetheless. He had no mouth, but he spoke. He had no hands, but he guided. He yielded himself to some higher principle, some transcendent reality. The Force was not a cause. It was not a movement. It was not a religious party. The Force was being itself, and Obi-wan was absorbed into the Force, yet paradoxically maintained his personhood. The Force overwhelms her suppliants, renders mute the passions, stands apart from the humdrum without becoming blasé or disinterested. When Obi-wan’s corpse disappears, the Star Wars universe is opened up into something ineffable. Lucas admits he cannot show or tell all that he has on his mind. There will always be something beautiful and powerful beyond the reach of his camera.

For Abrams, though, the Force was simply an invisible electrical socket. Or applied quantum physics. Or electromagnetism, and no one has ever died for electromagnetism. The Force was not god, not the divine nature. The Force was not a thing of sufficient personality to awaken. Rather, it simply turned itself on, like a lamp shaped like a lady’s leg might self-illumine at seven in the evening if set to a timer.

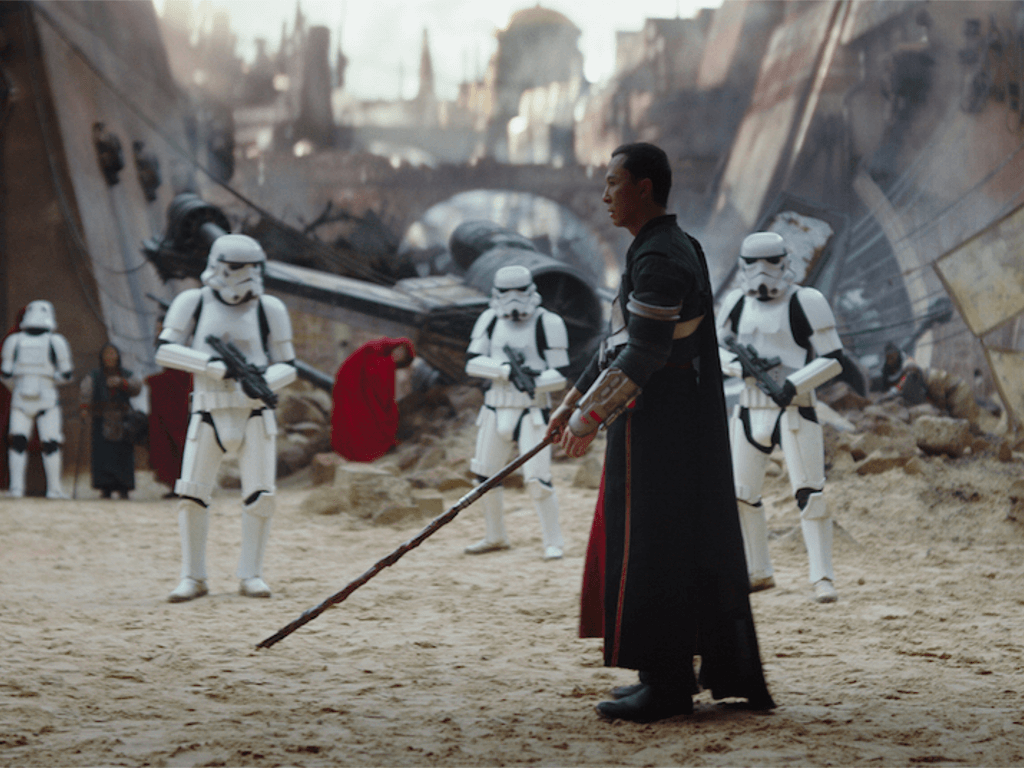

Which is why I liked Rogue One. This is a film which bristles with religious energy. The city of Jedha is alive with red-clad clergy carrying crosiers, monks, and sundry other clerics. The Empire is engaged in temple-plundering and the pious are violently enraged. Chirrut Îmwe, the blind mystic, centers the film. He bears witness to the Force, serves the Force, dies for the Force. He is evidence that the Force is omnipresent, transcendent. The Force does not exist for his sake. He practices Hesychasm, and so his life is tenuous, stilly and precariously balanced over death. Chirrut Îmwe serves whatever it was Obi-wan served. He is the first character since Return of the Jedi who might have rhapsodized Obi-wan’s death. When the Jesus prayer delivers Chirrut Îmwe through a gauntlet of gun fire, director Gareth Edwards might only be interested in Abram’s electrical socket. When Chirrut Îmwe dies shortly thereafter, we find the Force is, like the God of the Old Testament, condescending, but not subject to purely human affections. I would not be surprised to hear it was JJ Abrams himself who was leading the Empire to strip the Kyber from the temple in Jedha. He probably heard you could make good special effects with the stuff.

**SPOILER ALERT**

The fact that all the principle characters in Rogue One perish in the end enlists the film in Obi-wan’s service, even though Jyn is only, to co-opt Karl Rahner, an “anonymous servant of the Force.” The team which aids Jyn in the Scarif heist do so to atone for their sins, and unlike Rey, nothing comes easy for Jyn. She often finds the world unresponsive and must cobble together a meaningful life in the 11th hour. Rogue One is finally the story of a miserable daughter salvaging the right legacy of her father against a crowd of indifferent skeptics. While Rey finds the universe will increasingly bend to her needs, Jyn carries a torch for a despised dead man.

The Force Awakens proved Abrams knew how to use tracing paper. Rogue One strikes me as not so much the healthy work of director Edwards as that of screenwriter Chris Weitz, who has a wildly uneven filmography, but whose recent output is characterized by richly human films like About A Boy, proper myths like A Golden Compass, and shockingly faithful adaptations of fairy tales (Branagh’s Cinderella). Weitz is a self-described “lapsed Catholic crypto-Buddhist,” which is exactly the kind of person you want flying a Star Wars film. The latest in the franchise has no pretense of being a fun movie, but it does correct the benign inoffensiveness of The Force Awakens. It is— at very least— a thoroughly religious film, which is to say it deserves a spot in the canon.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.