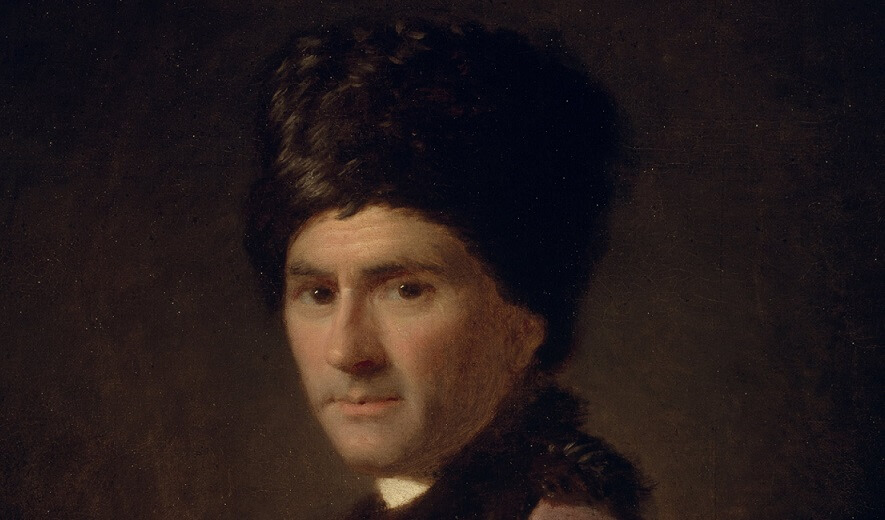

A Conservative Appreciation Of Rousseau

An unorthodox opinion on the nature of virtue slowly emerges over the course of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Social Contract. To have virtue, Rousseau suggests, means doing in an ordeal what you believe right in a moment of reflection. Of course, Rousseau is wrong— but he is not that wrong.

Put another way, given a comfortable chair, an hour to think, and a snifter of brandy to think over, what does a man believe theft is? Is he willing to live by that definition of theft with the chair gone, the brandy gone, and a burning hunger in his stomach?

As a nearly uncritical traditionalist, I don’t think this is a proper understanding of virtue. I will trust Boethius and Dante, Solomon and Plato for that. However, Rousseau does put the role of leisure front and center in his understanding of virtue, and this is an entirely Christian thing to do. His understanding of virtue has more to do with conscience, and conscience is a powerful arbiter of virtue. As St. James teaches in his epistle, “If anyone, then, knows the good they ought to do and does not do it, it is sin for them.”

As I described earlier, I have lately finished up a week living by a monastic rule of my own authoring. I vowed to wake early, jog, read the Scriptures, not curse, not snack between meals. I gave my students the task of writing a rule for themselves, as well. They have just assigned themselves grades, checked the grades against the approval of their abbot (a mother or father), and are now authoring long essays reflecting on how well their week as monks went. I did not do very well. I gave myself a low C.

The only way to make the rule effective, though, is to insist that students write their own. I asked, “How does the devil tempt you? What weaknesses do you have which the devil is apt to exploit? How can you give yourself a hedge of protection against your weaknesses?” Some students might suffer with great sins, others with minor sins. Either way, they had to compose a list of seven rules to follow which would help them draw close to God, shun the devil, and be virtuous.

I found it helpful to remind myself, over the course of the monastic week, that I had chosen these rules for myself. I had authored the rules not because I had to, but because I wanted to. I vowed to wake at 5:15, but I could have just as easily vowed to wake at 5:30. I did not have to cut myself off from snacks between meals, but I chose to. When I was hungry between meals, it was helpful to remind myself, “You don’t actually want to eat. What is it you actually want?” I had to remind myself, in the fashion of Rousseau, to do in the midst of an ordeal what I wanted to do in a moment of contemplation. In this way, I was able to bring contemplation and ease into difficul scenarios. Contemplation cuts us off from time and the ravages of time. We can always escape into our own hearts and speak privately with God there.

At the end of the week, however, I realized that while my rule was not Christianity itself, it was like Christianity in that it was voluntary. No one has to be Christian. The Christian religion is not compulsory. Christ warns His disciples that they must count the cost of following Him, and that they would be fools to not consider in advance what manner of lives He calls them to live. No one who sets his hand to the plow and looks back is worthy. “You must choose this day whom you will serve” is a statement Joshua makes to those who are already God’s people, and thus even the infant who is baptized is not compelled by force to remain in the fold. The sacraments aid the conscience, but do not coerce the conscience. Because Christianity leads unto genuine freedom, so it begins with a free decision. For this reason, when a man is tempted to lust or to get drunk, he should not say to himself, “I may not do this.” Instead, he should say, “I have already confessed to myself that I do not want to do this.”

It is for this reason that sin is always arbitrary. When I squander my time, I never do so according to plan. Ask me in the morning, “Gibbs, what would you like to do tonight?” and I will say, “I’d like to read my kids a story. Put them to bed about seven. Read a little. Watch an episode of Better Call Saul with Paula and then go to bed around ten.” I would never say, “Oh, I’d like to stay up until one in the morning or so, messing around on the internet— looking up rappers on Wikipedia, watching trailers for movies that I don’t want to see, looking for arguments on Facebook. Not really go to bed at one so much as have my unsatisfied consciousness ripped from my brain unwillingly after my body gives out for sheer exhaustion.” Although, guess which of these two possibilities I often find myself careening toward?

It is because I lack Rousseau’s virtue. It is because I forget what I want.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs is the director of The Classical Teaching Institute at The Ambrose School. He is the author of Something They Will Not Forget and Love What Lasts. He is the creator of Proverbial and the host of In the Trenches, a podcast for teachers. In addition to lecturing and consulting, he also teaches classic literature through GibbsClassical.com.