The Conversion of Constantine As Benedict Option

The state of international politics has lately made me wonder if the world doesn’t, in fact, end from time to time. Perhaps these occasional ends of the world simply leave no record in human history. The presence of a few very old things lying about the Earth is not enough to convince me otherwise.

Thoughts of the world’s end invariably turn my mind to what I think is arguably the least understood dramatic convention of human history, the deus ex machina. For a few ancient critics, the deus ex machina was evidence of writer’s block and the sloppy author resolved all things neatly and happily by way of a sudden intrusion of divine beneficence. Aristotle taught that the poet ought always “seek what is either necessary or probable,” and that “the solutions of plots too should come about as a result of the plot itself, and not from a contrivance.” While I agree that any given event in a story ought to be suggested in what came before, no man is capable of completely understanding all that has come before. This evening, thousands of human beings will come into existence who are entirely unique, unrepeatable, improbable, and eternally singular. If this rather obvious fact does not dismiss the demand for perfectly logical stories and perfectly rational histories, the disputing intellectual has not contemplated the mystery of personhood long enough.

If the deus ex machina has earned a bad reputation, we might had rather blame the accident of its usual employment at the end of a play rather than its employment whatsoever. St. Luke was not morally obligated to write anything after Acts 9, after all, and we might spend a moment wondering how the history of drama (or the art of writing history) might have been radically different if Luke’s history of the Church culminated in Jesus unnecessarily, improbably appearing before a particularly bloodthirsty Pharisee on his way to Damascus.

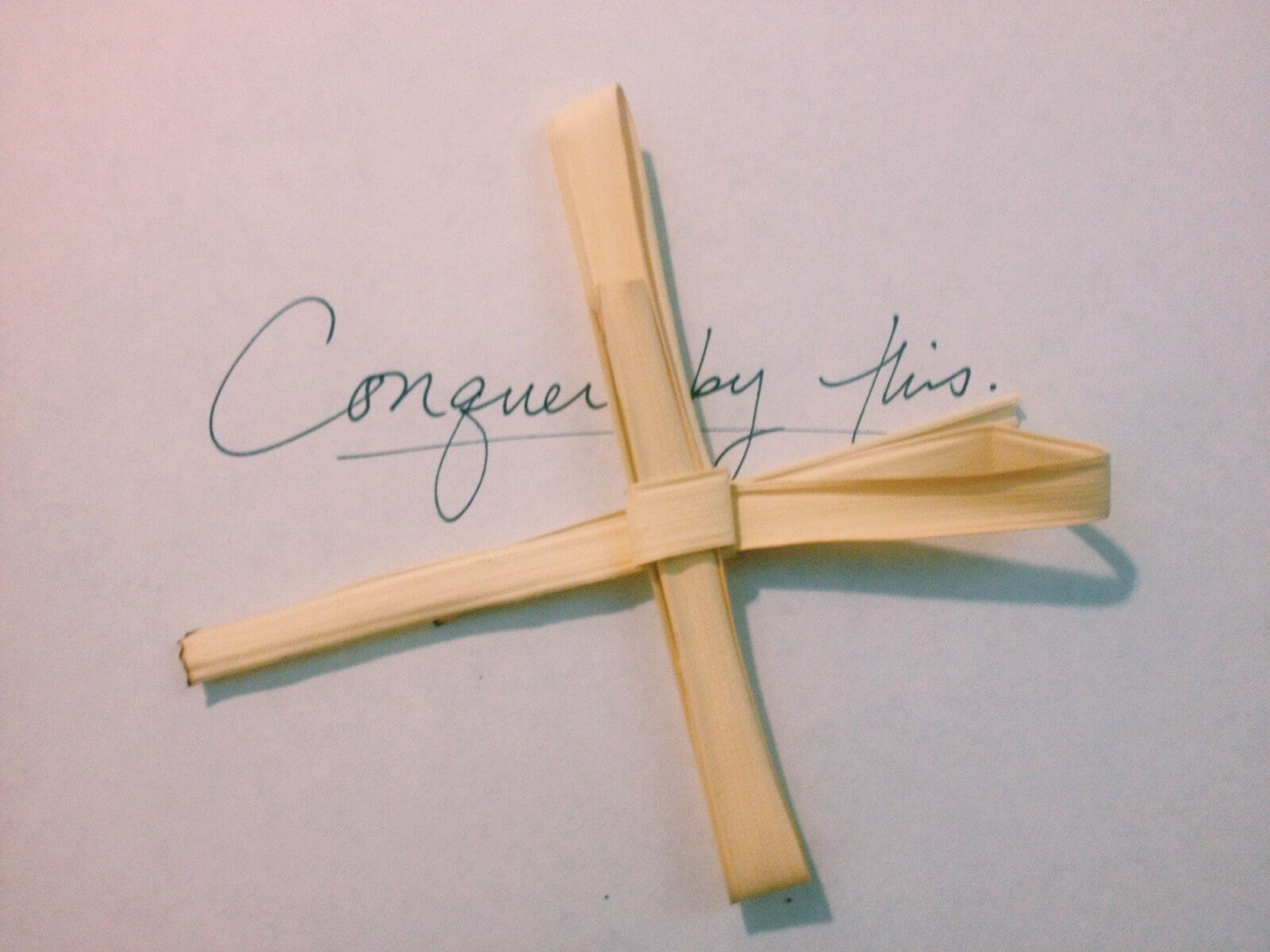

While the conversion of Constantine is a story worth taking at face value, it might also be read as a parable about Christian “cultural engagement.” The most significant event within Christian political history did not come about because of mission work, Christian books, Christian art, Christian culture, public debates with pagans, or even the quiet and compelling witness of Christian almsgiving, hospitals, or soup kitchens. Constantine’s conversion was an unrealistic intrusion into history. If his conversion was attributable to any earthly cause, there is the remotest chance the Church was praying for it, although I find it dubious to say any Christian was consciously praying for the emperor to convert. The political-prayer imagination of a Christian today largely grows out of Constantine’s conversion. Within the 3rd century Christian imagination, the salvation of the emperor was no more important than the salvation of a slave given that layman and clergyman alike thought the world would shortly come to end.

Current notions of cultural engagement often borrow from purely secular ideas about controlling the world. We speak of controlling the economy, we sue men for failing to predict earthquakes, we manipulate gender. Watching the world grasp after such power has inspired jealousy in the hearts of American Christians, and we have begun to think of culture as a thing like interest rates— a thing that can be consciously tinkered with to great effect. Any culture that can be tinkered with is no culture, though, but merely the avatar of culture. Any man who wants to tinker with culture has to use culture to tinker with it, and how does a man tinker with the culture with which he tinkers? In similar fashion, all worldviews are constructed with prior worldviews… all definitions are constructed from prior definitions… “I planted the seed, Apollos watered it, but God made it grow.” The mystery of growth, change, metamorphosis… these are divine mysteries which we will not conjur in a lab, in a conference, in a revival, in a Bible study, in an accountability group, in an OT survey class.

We should work out our salvation with fear and trembling and if a man may only do so by painting, then let him paint. If a man’s salvation is worked out with a guitar, fine. Let us not kid ourselves about changing the world, though. He would saves one soul saves the world entire, even if it is his own soul.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.