Conflict Resolution: A Defense Of Just Bottling It All Up

No one is more cautious about the value of words than professional writers. Having made a career of speaking for large and small crowds, and having written three books, a hundred film reviews, four hundred essays for this website— and having undertaken my fourteenth year of marriage— I would say I am skeptical of the idea that the best way for people to sort out their problems is to “just sit down and talk.”

Don’t get me wrong. I love to talk and to hear my friends talk. The virtue I chiefly value in my friends is their ability to hold a conversation. One of the greatest benefits of living on the campus of the school where I teach is that people stop by my apartment all the time, sit around my table, drink, and chat. My idea of the good life is a long dinner party wherein all the guests stay until late and the conversation moves from light to weighty subjects as the evening goes on. Such parties should disband only after everyone has simultaneously come to some epiphany, the kind of epiphany that can only be summoned when many friends incline their hearts toward one another and seek the truth.

Of course, the point of a dinner party is not for guests to sort out their problems with one another.

My skeptical stance toward the idea that interpersonal conflicts are best solved through conversation is chiefly derived from two things: first, a staggering amount of evidence and personal experience which suggests the contrary, and second, a staggering lack of biblical evidence to support the claim. Upon saying this, I suppose there is a certain kind of reader who will respond, “Oh, so you think it is better to fight?” However, such reactions only go to my second objection. Modern people have been trained to believe all problems are solved either by violence or by calmly, rationally sitting down to talk. To the contrary, Christian tradition suggests a rather wide range of much better possibilities— like doing nothing, for example.

In his remarkable essay “On Charon’s Wharf,” the late Andres Dubus describes his relief that the Eucharist is not a conversation and his dependence on similar Eucharistic moments with his wife, wherein they make scrambled eggs together, eat together, but do not attempt to conversation. He alludes to what might be a troubled marriage or simply be a common marriage, and says:

With words we create genies which rise on the table between us, and fearfully we watch them hurt each other; they look like us, they sound like us, but they are not us, and we want to call them back, see them disappear like shriveling clouds back into our throats, down into our hearts where they can join our other selves and be forced again into their true size…

Elsewhere, Dubus laments that words are “at times too powerful or fragile,” and that words sometimes become “autonomous little demons who like to form their own parade and march away, leaving us behind.” And this from a professional writer, a man whose livelihood depended on people reading his words— and, perhaps, understanding and believing his words, as well.

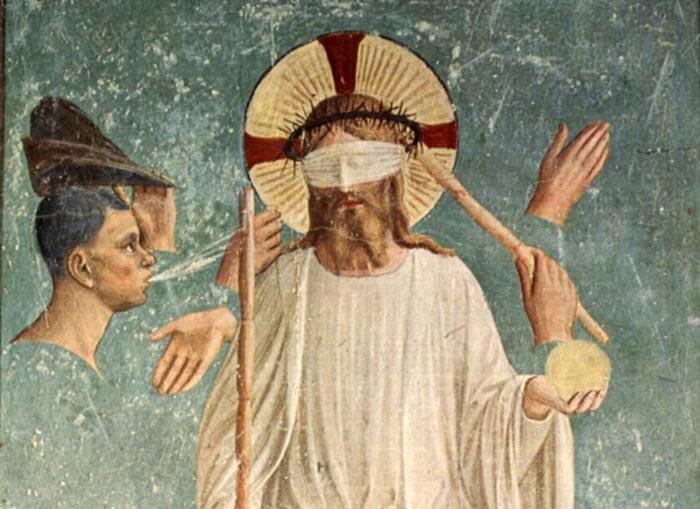

CS Lewis was similarly glum about words. In Till We Have Faces, Orual recalls the Fox teaching her that saying what you really mean is the “whole art and joy of words,” but Orual calls this “a glib saying” and remarks with fear that when a man is finally made to account for himself at the Great Judgement, he will not think of “the joy of words.” Our lives build to a moment wherein we will be quite terrified to speak, though some of that terror should be present in everything we say prior to the Judgment, as well.

The modern confidence in conversation as the Great Solution is borrowed from Enlightened atheists of yesteryear who not only denied such a Judgement awaited men but believed religious ceremonies mere superstition and mocked the irrationality of vows and oaths. Modern men were to be joined together by reason, not by ritual. To this day, when we speak of “talking through our problems” we often say we are going to sit down “like reasonable people” or “rational human beings,” for we are confident reasonable people who disagree must simply have a misunderstanding and that the orderly pursuit of truth will clarify any misperceptions of reality. On the other hand, Solomon teaches, “In many words, sin is not absent.”

Speaking from my fifteenth year as a teacher, I can report most of the “sit down and talk” conversations I’ve had with parents who are angry with me simply make things worse. That might be my fault, it might be theirs, or it might be that people who are upset with each other shouldn’t expect reasonable, rational conversations to make problems go away. To understand another person’s position is not to agree with it. In the midst of many troubled conversations, I have expressed myself quite clearly and without ambiguity, and others have done the same; it occasionally results in a good-natured handshake.

The fact such conversations rarely work is not a reason to avoid them, for polite and rational conversation between dissenting parties is often part of a sane policy of conflict resolution which any school or church or institution must have. I’m not some idealist arguing that real Christians shouldn’t need conflict resolution policies— that’s daft. Rather, my point is that very few conflicts are resolved through conversation itself. Sitting down and talking is better than gossip, better than airing out complaints on social media— but those latter options also involve words, speech. While I appreciate the fact the so-called “Matthew 18 principle” prohibits gossip and slander, many Christians treat the “Matthew 18 principle” as a kind of theological-bureaucratic rigmarole that must be blown through before the real work of dismantling someone’s reputation or career can be “righteously” undertaken. I find it telling that the eighteenth chapter of Matthew existed for nearly 2000 years before modern Christians transformed it into procedural paperwork. For my money, the chief value of the “Matthew 18 principle” is that it slows people down and keeps them relatively quiet for longer than they’d like. I have more confidence in quietude and patience resolving conflict than sitting down to talk. On occasions wherein my wife annoys me to the point I want to confront her and say something, the far better solution is just to go to bed, to dream, and to wait for the joy which comes in the morning, as David writes in Psalm 30. Allow me to suggest that most real conflict resolution is accomplished by the Holy Spirit when we are caught in the privacy of our own thought, when we are standing in Church listening to the Word, or those helpless moments wherein we contemplate the relative innocence of children and just how far we have strayed from God since birth.

I am not suggesting that sitting down and talking through problems never makes things better, but that our confidence in sitting down and talking is often misplaced. Even when sitting down and talking “works,” the real work is often accomplished by contemplation and the cooling of passions which follows in the weeks and weeks which follow sitting down and talking. The age of social media has led to endless chatter about race and gender, nonetheless, I still regularly encounter people who claim, “Our problems with race will not go away and until we can openly discuss them.” The idea that we talk too much about important issues is blasphemous. Americans used to believe that throwing enough money at a problem would make it go away. We now believe that throwing enough words at our problems is the answer. Nonetheless, St. James says we should “quick to listen,” which does not mean “quick to engage in conversation.”

It is pleasant to think that our problems can be talked through, but if we’re honest with ourselves we will admit the idea is simply too good to be true— talking is just too quick, too easy, too straight forward. “Hard conversations” do exist and speaking (and listening) can feel a good bit like dying, but for the vast majority of the annoyances, vexations, complaints, irritations, insults, and indignations that must be suffered while living in community, the most reliable solutions are prayer, confession, and good old-fashioned bottling-it-up while time wears away the rough edges of offense. This is obviously not the case with matters of abuse, gross negligence, and crime, however, no one believes that merely talking through abuse and crime will cure such evils. Rather, the problems we are encouraged to sit down and talk through typically reside in the profoundly spacious realm of “conflict.”

The goal in conflict resolution is to make all parties feel respected and honored, which sounds lovely, but it often means both sides enter the conversation looking for the respect they believe they are owed. Bottling it up, on the other hand, means absorbing the offense, refusing the right to speak, the right to defend yourself, the right to enter into a conversation wherein respect and honor are “guaranteed.” Of course, we rarely receive the respect and honor we think we are due. Bottling it up often means forgoing the luxury of explaining yourself, passing up the possibility of being understood. Bottling it up hurts and all hurt is bad— or so claims the Modern man. On the other hand, God sees the truth, but waits.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.