Come, Desire of Nations, Come…

Why study the pagans? The question threatens to become rote, dull and boring because we have become so accustomed to its’ formally, logically apt answers.

This week, a host of classes at Trinitas will celebrate Zeus’s Family Reunion, an annual feast day wherein students dress up as gods and goddesses and give presentations on Greek mythology. I was asked to deliver a brief apologia at the beginning of the feast to describe why Christians study the gods and goddesses.

Why study the pagans? The question threatens to become rote, dull and boring because we have become so accustomed to its’ formally, logically apt answers. We study the pagans because they are old, and their stories have stood the test of time. We study the pagans because their poetry is beautiful, and wherever we have found Beauty, we have found at least a glimpse of our own God. Or perhaps we offer a more theologically astute answer to the question. We should study the pagans because St Paul studied the pagans, and he was convinced enough of their value to quote the great pre-Socratic philosopher Epimenides twice, once in his sermon on Mars Hill and later in an epistle to Titus. St Paul quotes Epimenides’ Cretica as though it were an authoritative text, true, an apt description of the world, and of his own God.

Epimenides hailed from Crete about the seventh century, and lived during a time when a heresy had arisen that Zeus was mortal, just like a man. Epimenides understood, however, that the divine nature was not like gold or silver or stone, something shaped by art or man’s devising, but that the divine nature transcended all human comprehension. Epimenides writes:

They fashioned a tomb for you, holy and high one,

Cretans, always liars, evil beasts, idle bellies.

But you are not dead: you live and abide forever,

For in you we live and move and have our being.

While speaking to the pagan philosophers, the Epicureans and the Stoics, on Mars Hill, Paul quotes Epimenides and borrows his description of Zeus, aptly fitting it to the true God. Epimenides knew What God Was, he knew How God Was, he knew Where God was, but he did not know God’s name.

So St Paul studied the pagans and found them helpful in coming to know his own God, the true God. St Paul did not study the pagans merely to see how they got it all wrong, although there was certainly enough of that; he also studied the pagans to see how God had been merciful to them, and led them to some truth, albeit in mysterious, anonymous manners. In the City of God, St Augustine reflects on the fact that, in the Gospels, demons are forever, begrudgingly acknowledging Who Christ is when He stands in their presence; could it not also be that the demons the pagans worshipped had, for centuries, unknowingly and begrudgingly, acknowledged the goodness of God to their own false worshippers?

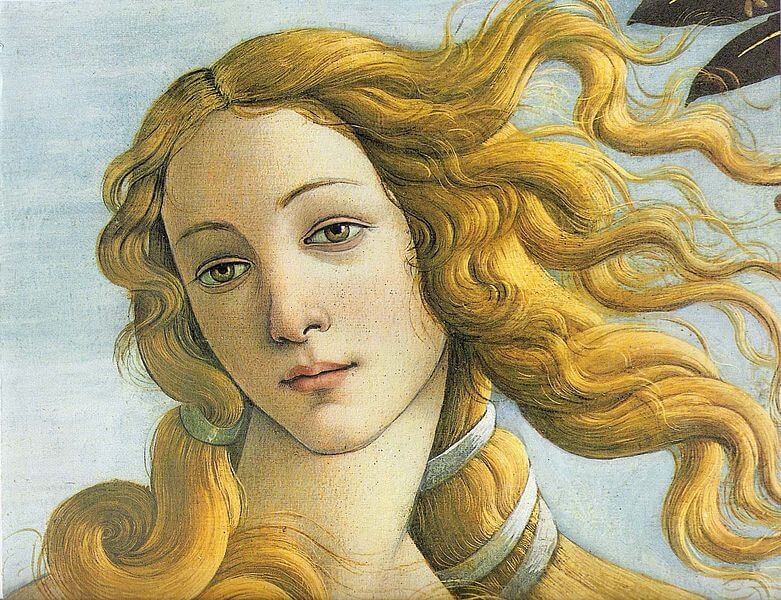

While many theologians have suggested the gods worshipped by the pagans, like Jupiter and Zeus and Aphrodite, were demons, it seems that God had merciful purposes even in the fanciful myths and idolatries of the Greeks and Romans. The meteoric rise of Christianity in the third and fourth century suggests the moral imaginations of the pagans had been tutored for years to want what was good, even while they waited in horror until that good thing should come. In the story of Prometheus, we find a God who stands on behalf of man, fights for man against the darkness, ascends a mountain to retrieve divine knowledge in the form of fire and deliver it to man as a free gift. In the story of Christ, we find the God Who becomes a man, fights for man against the darkness of sin, ascends from a mountain and sends the Holy Spirit to man as tongues of fire. In the story of Dionysus’ birth, we find his mother Semele, pregnant with Dionysus, obliterated after Zeus is transfigured before her; sadly, this is a common occurrence in pagan theology. The god reveals his glory to man, and the revelation of his glory destroys the human who bears witness, or the god retreats from the human who has born witness to his glory, either in arrogance or in shame. A sadness permeates every transfiguration of a pagan god; how sublime, then, how gracious, when Christ is transfigured before Peter, James and John, and then they all return down Mt Tabor, in good health, to continue their work. Or what of Chiron, the noble centaur, the master of the healing arts, who, while divine, is willing to descend into Hades and rescue Prometheus, man’s first representative, from his enslavement? In Hades, the deathless Chiron is pierced through with a poisoned arrow and mysteriously dies; others he saved, but he could not save himself.

I might go on and on, but of course, for every aspect of a Greek myth which brilliantly, enticingly points to Christ, some other aspect of the myth is ill-fitting and unworthy. Chiron is accidentally shot with an arrow, for instance. The distinctive gifts of motherhood are maligned in the story of Dionysus’ birth, for just before Semele is annihilated by the Beatific Vision, Zeus mystically snatches Dionysus from Semele’s womb and the unborn child is installed in Zeus’s thigh, where he comes to term. In a spirit of divine discontent and protest, we might comb over each Greek myth for the daffy, the absurd, the idiotic, the demonic, and strain out quite a lot.

At the same time, the myths so aptly and often point to Christ, we might wonder how they often got so close. In his sermon on Mars Hill, St Paul offers an answer. And He has made from one blood every nation of men to dwell on all the face of the earth, and has determined their preappointed times and the boundaries of their dwellings, so that they should seek the Lord, in the hope that they might grope for Him and find Him, though He is not far from each one of us; for in Him we live and move and have our being, as also some of your own poets have said, ‘For we are also His offspring.’ Paul here speaks of God’s sovereign plan for all the gentile nations of the Earth. When do men go out to dwell on all the face of the earth? In Genesis 11, after God has confused the languages of the man at Babel, he “scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth.” And where did God scatter them? Well, when St. Paul refers to the “preappointed times” of the pagans, and “the boundaries of their dwellings,” he is referring to their geographical locations and the passing of the seasons in those particular places. Some nations are scattered to the north, to cold and desolate and mountainous regions, where winter is long and summer short. Some nations are scattered to the south, to milder climates where crops grow easily and labor is quickly rewarded. Of course, in your study of mythology, you’ve no doubt found that most pagan mythology is deeply rooted in the earth, in the seasons. A mountain is worshipped, or a flower which only grows in a certain grove, or the rising and flooding of a local river at a certain time of year is symbolic of the birth or death of some god. These mountains, flowers and floods— which pour into the mythology of the Greeks and Romans and Africans and so forth— are all described by St Paul as being “determined” by God so that the pagans should seek the Lord, in the hope that they might grope for Him and find Him. Which simply means that when you read of the story of Demeter and Persephone, or Prometheus and Epimetheus, you are bearing witness to the pagan struggle, the pagan hope, the pagan groping for the true God.

How merciful was God to these pagans? How helpful were the pagan myths in bringing pagans to the point they could accept the Gospel? While the Jews were God’s chosen people, this should by no means suggest that God hated the pagan nations. In the 200s and 300s AD, the number of pagans who converted to Christianity was astronomical. Some better historians of our day (most notably R.A. Markus) estimate no more than fifteen percent of the Roman Empire was baptized in the years just prior to Constantine’s ascendance to the Roman throne. Christianity was legalized, and hundred years later, that number had quadrupled. Who were all these people that converted to Christianity? Pagans. Devotees of Jupiter. Devotees of Sol Invictus. We might go so far as to say that the myths had well prepared pagans to receive the Gospel. The Gospel of Jesus Christ fulfills the errors, the misapprehensions, the missteps, the misreadings, the forgetfulness and “the times of ignorance which God overlooked” in the work of Ovid or Hesiod or Homer. Yet the Gospel does not obliterate the myths, for the myths are full of the good desires of the nations— desires for a God Man, for a dying God, for a selfless God— for as we sing every Christmas, “Come, desire of nations, come…”

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.