Classical Education Needs A Few Dogmas

Classical Christian schools need a separate statement of faith which deals with classical issues and prejudices.

Most Christian schools maintain a rudimentary statement of faith which parents are either required to believe, or simply consent to their children being taught. While I have made no sweeping survey, most of these statements of faith contain a dozen or so creedal claims about Christ, the Trinity, the Scriptures, the Atonement, and define “primary doctrine” issues which teachers can and should speak about definitively and dogmatically. The statement of faith is not subject to debate in the classroom, although secondary doctrines may be approached generally and diverse opinions considered. While Protestants and Catholics alike hold to the doctrine of Christ’s two natures, not all Christians agree on, say, the perpetual virginity of Mary, and so teachers should not use the lectern to dogmatically pronounce their belief on the matter. Enjoying harmony and comradery in the classroom depends in some manner on assumed, shared convictions, and a short, elegant statement of faith goes far in establishing such harmony.

While a simple statement of faith accounts for the Christian aspect of a “classical Christian school,” most schools are without a similarly straightforward document which establishes the classical aspect. The classical aspect is often spoken to on the school website, and teachers and parents might be required to read a book by Taylor, Sayers, or Wilson, but after working in classical education for more than ten years, I feel confident in saying that there is still no broad consensus on what “classical” entails. Neither is it the case that staff and faculty all agree on what “classical” means, while parents lag behind or disagree. Rather, ask ten people at your school what “classical” means and you will get eleven different answers.

A classical Christian school community may claim Baptist, Catholic, Presbyterian, Orthodox, Anglican, and Evangelical families who, despite profound disagreements on sacraments and ecclesiology are nonetheless of one mind on the dual authorship of Scripture, the ethics commanded in the Sermon on the Mount, the immortality of the soul, and two or six dozen other matters. However, there are no widely accepted classical prejudices. I say this because, from time to time, I have heard parents say things like, “What you really need at sixteen is the space and freedom to figure out who you are,” or, “A good school should help you find your voice,” or, “What’s most important is deciding how to be true to yourself.” I have no interest in arguing against any of these claims. They are not classical claims at all, though. If a man wants to believe that a sixteen year old needs space and freedom to figure out who he is, that is fine, but he should expect a significant hassle from a classical school while trying to live according to such ideals. I would think the same thing if I was walking into Ruth’s Chris with a friend who excitedly said, “The best thing about this place is the nacho bar.”

In the same way that a school’s statement of faith removes certain Christian ideals from the realm of debate, a school should also maintain a body of classical ideals which are similarly intractable. If a school permits atheists and skeptics to enroll, fine, although teachers should not be forced to field questions wherein conventions of Christian history and theology must be freshly articulated and defended a dozen times during every history lesson. If a skeptic wants to say, “Believing in God is like believing in unicorns,” this is also fine, just not during class. The classroom is a place wherein the Lordship of Christ is built upon, not a place where it needs to be established.

Establishing Christian standards for a school is easy enough, though it is far, far easier to be Christian than it is to be classical. Being “classical” is an additional burden placed upon being Christian, kind of like being a Nazarite, or a monk, a wife, or a senator. The duties of a monk or wife or senator are spelled out in certain oaths which are taken at the point of entry, and while I am not suggesting there should be classical oaths, I am saying every school ought to have a classical credo. The abbot should not have to argue anew every morning that fasting or chastity are viable spiritual disciplines, but should be able to move on to the work of helping the brothers accomplish these shared, assumed goals. A monastery is a place for people who already agree on certain well-defined habits of being, not a mission field where everything is up for grabs.

Because classicism is often tenuously articulated up front, a great many teachers must regularly try to persuade parents and students alike of boilerplate classical rules in the middle of the game. Classical prejudices are undefined, and so students approach teachers a week before the end of the quarter and say, “I was wondering what I could do to raise my grade,” which is simply the classical equivalent of telling a Lutheran minister, “I was wondering if I could buy an indulgence for a lie I am going to tell tonight.” Theological quibbling aside, wrong continent and wrong century.

To the end of establishing something like a classical statement of faith, which it might be better to call a classical statement of confidences, I offer this series of claims and propose they are essential to justly and fairly calling a school classical.

1. In the classroom, no privilege is granted to self-expression. When he encountered Christ outside the Jordan, St. John the Baptist said, “I must decrease and He must increase.” The Christian life is one of continual self-effacement, self-denial, self-awareness, and selflessness. The only fitting way for a Christian to figure himself out is to contemplate God, love God, and serve God in piety and deference for God’s friends. Students come to a classical Christian school to learn virtue, not to express themselves. Self-expression is at odds with learning virtue. The mostly wildly creative artists who ever lived (Bach, Caravaggio, El Greco, Milton) were chiefly concerned with the glory of God and the humility of man, not with the self, and yet their works yet feel deeply imbued with living power every time we return to them. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, on the other hand, were typical to the 20th in their enchantment with self-expression and so they created works which continue to inspire anger, hatred, pretension, and despair.

2. The classical classroom gives preference to old things. A classical school should be a place for people who don’t go into panic mode when they hear someone say, “Old things are better than new things.” The sheer volume of confusion among American Christians about what “chronological snobbery” actually means could knock over the Hoover Dam, and classical schools need to take up the difficult work of explaining why they teach Plato and not Plantinga, Plotinus and not Piper, but also why classicists do not care about learning styles or fidget spinners or any flavor-of-the-week pedagogical trend supported by “recent studies show…” I have written at length on this subject here and here and here.

3. In the classroom, there is little room for recent trends and new prejudices. Our world is at war with old things and desperately in love with all things new. The average newspaper or television station uses the word “Medieval” as a euphemism for tasteless, brutal, and crude. We have made a virtue out of all things new. When very terrible things happen, we say, “Is this very terrible thing still happening in the year 2018?” because even many Trinitarians of our day reason like materialists and progressivists. We assume that 2018 would be idyllic, utopian, if only we could shake the last few nasty sticky remembrances of the old world from our fingers. But the classical classroom is a safe place for old beliefs and ideas.

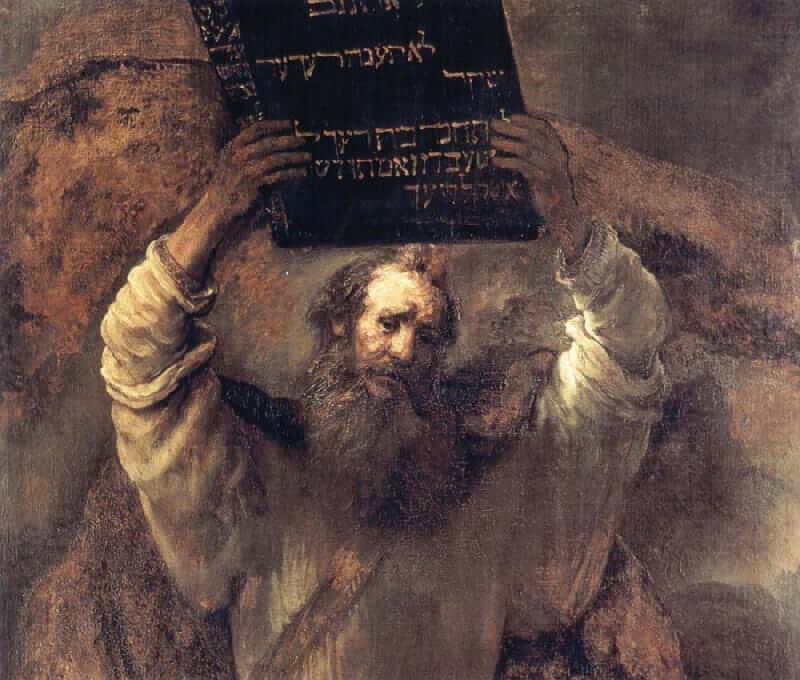

Generally speaking, if no said it a hundred years ago, it does not deserve time or space in the classroom. Perhaps it is true that potato chips and Pepsi can be served as the Eucharist, but if no one said it a hundred years ago, the claim is without purchasing power in the classical classroom. If a student goes to a church wherein the Eucharist is chips and pop, he should be aware that his personal convictions will simply not be granted the same deference in the classroom which the personal convictions of, say, a Latin mass Roman Catholic will receive, simply because Latin mass Roman Catholics are profoundly responsible for the classical tradition and the chips-and-pop Eucharist kind of Christian is not. I still must submerge my own personal beliefs from time to time, although since I began teaching at a classical school more than a decade ago, I have become increasingly enchanted with the world of long ago. I would like to be able to answer any question my students ask me about personal convictions with a quote from Moses, Christ, St. Paul, Boethius, Dante, St. Gregory of Nyssa, or Edmund Burke, though I am probably still 20 or 30 years away from it.

There are a great many claims which my students would like to make about race and gender in the classroom, but if the claims were not made a hundred years ago, and no one is likely to make those claims a hundred years from now, then they have no place in the classical classroom. The current zeitgeist is yet to put forward a significant claim about race or gender which holds together for more than a few years before disintegrating. When I was a child, everyone knew that being “colorblind” was the best tool in fighting racism. Today, no one claims this. Twenty years from now, we will have moved on to some new articulation of race wherein our grandchildren will condemn us more vehemently than we condemn our grandparents. The classical classroom simply demands that beliefs have survived the trial of time before they will be granted admittance. The classicist wants to know, “If your grandparents didn’t believe it, and your grandchildren won’t believe it, why should you? What will you gain from believing it apart from the acceptance and approval of a few friends?”

Coda. A statement of classical confidences would be of immense value so far as gatekeeping and conflict resolution are concerned, for the most acrimonious arguments which emerge in the course of a school year, whether between parents and teachers or teachers and students or teachers and other teachers, are not as frequently based on Christian differences as they are on classical differences. Teachers also need a more basic rubric for judging lessons, illustrations, tests, quizzes, conversations, discussions, and lectures on the fly. Classicism is still a conversation, but a conversation presumes a shared language, symbols, and grammar. So far as theology goes, most ecumenical Christian schools already have this down pat. So far as classicism is concerned, we don’t yet know which direction is North.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.