A Classical Defense Of Craft Beer

Earlier today, I walked into a beer joint looking for a little refreshment. The place was having a slow afternoon. A bartender, myself, and one other customer made three. I had my choice of sixty beers on draught and another sixty in bottles from a cooler. I began talking through the possibilities with the bartender, accepting samples of beers I inquired about. Something from Perennial, something from Dogfish Head, something imported from Munich I had never heard before. The other patron offered helpful and critical comments as we talked through highlights from the menu. We all agreed that the World Wide Stout was very good, not easy to find, and worth the price. I got a short pour.

For the next twenty minutes, we compared notes on favorite breweries, traded opinions about rarities, struggled to find precise terms to describe what we enjoyed. Halfway through the conversation, the other patron purchased a twelve ounce bottle of Hive 56, a dark sour honey ale from Allagash. The single bottle was more than thirteen dollars, though he poured himself a small glass then split a generous second portion between myself and the bartender in two smaller glasses, insisting we try it. In my experience, such behavior is typical of men buying expensive beer. This kind of thing has happened to me at craft beer joints more times than I can count.

What I find remarkable about such interactions is how little the patrons of a bar want to know about each other. The fellow who poured me a liberal draught of his expensive drink this afternoon did not ask about my political or religious convictions before doing so. He did not ask me what I thought of abortion, Donald Trump, statues of Robert E. Lee, taxes, or gay marriage, and neither did I ask him any of these questions. It was enough to encounter a fellow human being who loved the same things he loved and was willing to pay through the nose for them. We enjoyed pleasant conversation for nearly half an hour without ever finding any matter to get huffy over. Perhaps in a bygone era, we could have complained sympathetically to one another about women or the failures of the local baseball club, but two men who randomly encounter one another can no longer assume similar prejudices on these fronts. However, the average glass of beer at the bar in question was seven dollars. At such prices, few people accidentally wander in. It was enough that we both loved the same things. Having found a matter of common affection, neither of us sought out deeper matters. “You love this. I love this. Let’s talk about that, stranger.”

The encounter seemed all the more profound having spent a week lecturing to four separate sections of Modern European Humanities classes on 17th century European religious anxieties. The typical French onion farmer of the 10th century was largely unaware that he even had philosophical beliefs. Everyone simply accepted the world as it was, as it had been handed down. That onion farmer never met anyone who believed otherwise and carried on as though all of mankind was in essential agreement over the fundamentals— if there even were such things as fundamentals in the 10th century, which I doubt. However, into the Modern Era, that onion farmer became increasingly aware of his beliefs because he had to defend them. If he lived in the Holy Roman Empire, no matter what he believed about the Eucharist, some massive voice was shouting at him that he was going to Hell. Real presence? Damnable, so say some. Mere memorial? Damnable, so say others. Given that the average onion farmer had his health to worry about, not to mention a wife, children, bills, the crops, and so forth, there was very little time to study the philosophical and theological issues pressing in upon him. Regardless of what he believed, a great many men who spoke his own language and bled his shade of blood differed. He made an arbitrary choice, then endured much shouting. The anxiety was great, and when Modernists insisted religion was more trouble than it was worth, and that religion ought to be pushed to the side of society that there might be peace, the average European require little convincing.

Of course, the same anxieties which overwhelmed many 17th century Europeans have become standard features of Modern life. Catholics and Protestants are often friends in modern America, even while they sometimes eye one another suspiciously. As someone who works in an ecumenical school, I am genuinely grateful for the ecumenical movement of the early 20th century, and I believe that classical education is a part of modern society uniquely suited to ecumenical agreements. My students often claim that it is better to live in a pluralist society where a man’s beliefs are constantly challenged, for no one knows what they really believe until they are put to some kind of test. Iron sharpens iron. Having seen friends and graduates often succumb to the worst excesses and idiosyncrasies of the current zeitgeist, I am hardly persuaded.

Still, I feel the same pull Late Antique Christians felt to civic unity. When pagan festivals and rituals continued after the rise of Christianity in the 4th century, the average layman was often in attendance. The arguments the laity offered their priests for going to festivals honoring pagan gods will be familiar to any parent who has teenage children. We are just going to talk. It is not a big deal. Everyone is going to be there. It’s just a good time. As Late Antiquity carried on, a great many pagan festivals were jettisoned, and the others were slowly conformed to Christian dogma and prophecy. Some were irredeemable. Other festivals and civic institutions were simply “the desire of nations,” which Christianity fulfilled.

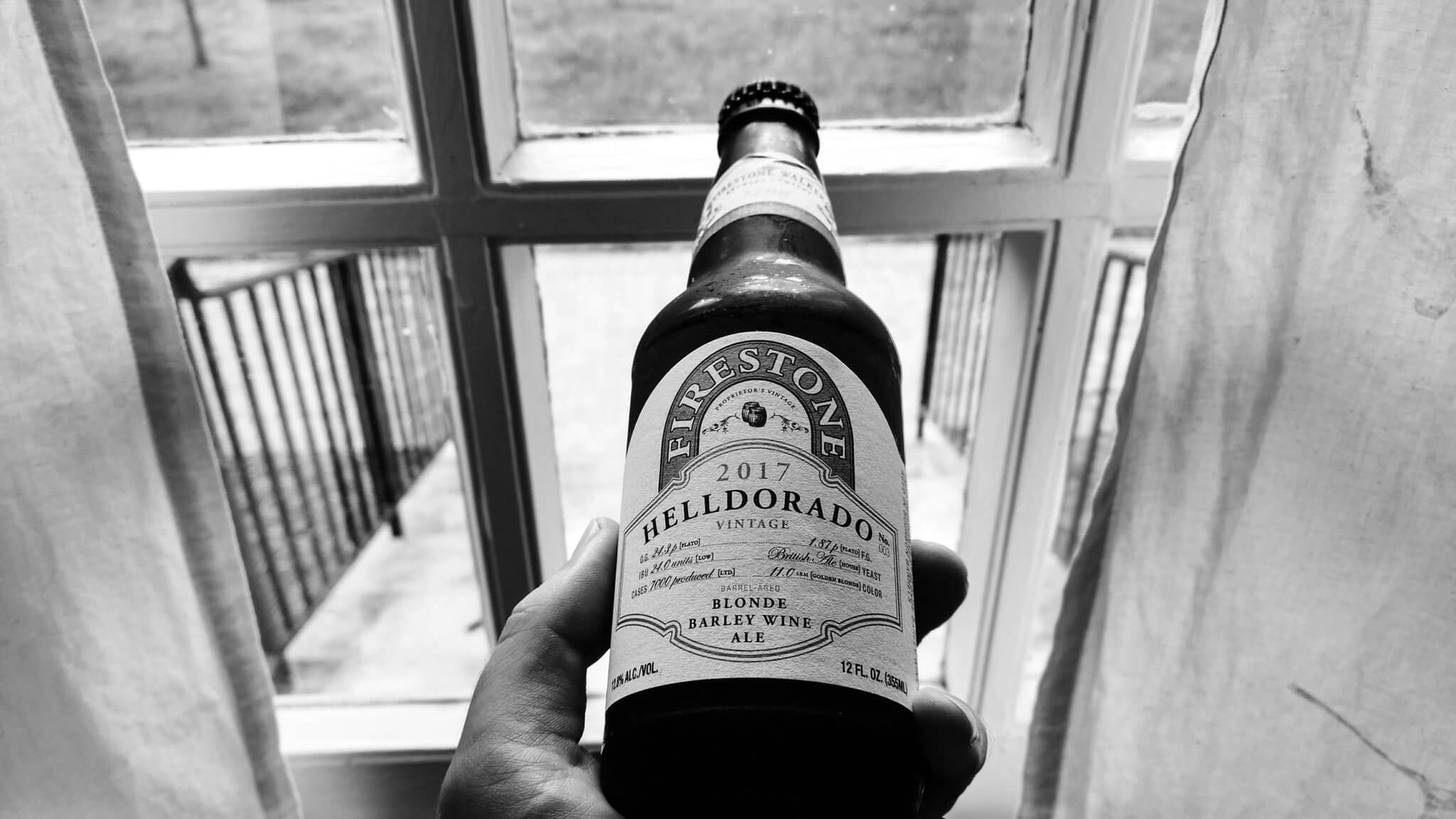

In a society which is daily finding new ways to break itself and fracture into smaller and smaller segments, there are few civic festivals left which might bind Americans together. I have lately consented to let my children go trick-or-treating. Perhaps trick-or-treating is just craft beer for the elementary school set. I am very thankful for craft beer bars and the fastidious aficionados who inhabit them and overpay for obscure saisons, limited edition imperial stouts, and esoteric Italian sour goses. I am happy to share a drink, a spirit, with these men and bypass the matters of politics. “Let us not mention the zeitgeist, gentleman, for it is a filthy and divisive spirit.” We will find ways to disagree once we leave the bar, but let us be friends for now. Men are naturally friends, and enemies only at some bidding of the devil. The bar becomes an oasis, a refuge from the ever present demands to debate and argue and “give an account of the hope” I have. I am modern by default, and I need an occasional respite from arguing. I want to love something, and I want to hear about what strangers love, and I want to agree with them.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.