Christ The Student: Student As A Divine Office Of God.

Christ has often been seen as Prophet, Priest, and King, and following an Augustinian theory of learning, He has often been viewed as the Teacher as well. We have not often imagined Christ as the Student, though. Should we?

The act of learning was such a mystery to Plato that he claimed learning was nothing more than remembering what had been learned in eons past. In a manner of speaking, language is an irreducibly complex machine. No one word is definable without previous words, and previous words require previous words. Look up any word in Webster’s and you’ll get four or five salient words in the definition. Look each of those words up and you’ll get four or five salient words. The definitions of those salient words will invariably retread the first round of salient words. How could the first word have ever been spoken? Did not the first word require previous words? Augustine recognized the difficulty of learning and claimed that ultimately Christ taught all things; the act of learning transcends human capacity and requires divine grace, no less than turning a few loaves of bread into a few thousand loaves of bread.

Of course, any seasoned teacher will tell you that the teacher is simply the foremost student. The teacher is the longest running student. The teacher is the student who talks the most. The teacher is the student who grades the papers. There are times when I think there is little qualitative difference between myself and my sophomore class. I’ve simply been at it for longer.However, if the teacher is simply the foremost student, what does this mean for Christ the teacher? In what way could Christ, the Light which illumines all, possibly be a student?

If there is a case to be made in Scripture for Christ the Student, John the Baptist is His foremost teacher. Jesus learns to fight the devil from John; John battles viperous Pharisees in the wilderness, and Christ goes into the wilderness to battle the serpent shortly after meeting John. Jesus learns to criticize the Pharisees from John; John calls the Pharisees a “brood of vipers” in Matthew 3, and twenty chapters later, Christ does the same. Christ learns to speak of the Judgment from John; while Sheol was traditionally a dark, deep, watery place, John speaks of the judgment as an “unquenchable fire,” and Jesus teaches in Mark 9 that hell is a place where “fire is not quenched.” Christ learns ministry from John; John’s ministry of repentance spreads by baptism with water, and Christ’s ministry spreads by baptism with fire. Christ learns charity from John; as John preaches, “He who has two tunics, let him give to him who has none,” so Christ doubles the commandment of generosity and teaches, “And from him who takes away your cloak, do not withhold your tunic either.” It might even be said that John taught Christ how to die. John is slaughtered by a reluctant politico who does not want to embarrass himself and renege on a generous promise at a feast, and so is Christ.

So there are many parallels between John’s life and Christ’s life. Big deal. Did we not already know about archetypes? Have we not read enough about Christ reliving the history of Israel that we need Christ to relive John’s life, as well? Is this nothing more than proof the Gospel writers knew something of foreshadowing and theme?

It is far more.

Sadly, living downstream of the Enlightenment, we tend to think of time in a linear and progressive fashion, which more or less reduces the prophets of the Old Testament to the level of mere fortune tellers. They saw the future and reported back on it in the present. Because the future is uncertain, only those who have access to transcendent power can know the future in advance. Or so we say. Telling the future is far more common than it might seem, though, and according to many a Medieval philosopher, actually quite easy to do (given the right tools), even while doing so is profoundly impious and sinful. The Delphic oracle was a reliable witness of future events for centuries, and, call me romantic, but I refuse to believe every last fortune teller alive today is kept afloat by mere vagaries and gullible customers.

Perhaps the Old Testament prophets could see into the future in a way similar to a character in reel 2 of a film having a look at real 5, but such a model of time is a recent invention. I’ve always been fascinated by Christ as the “desire of nations,” though, which suggests a far different nature to the prophetic work. In drawing so near to God as to speak on His behalf, the prophets expressed the deepest longings of humanity; in His infinite condescension to man, Christ fulfilled the deepest longings of man. The Old Testament might be read as a perfection of man’s desire, and Christ comes as the fulfillment of that desire. When Christ does something “so that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by Elias,” He is not proving Himself the Christ as though by a checklist of attributes, but giving man what man has desperately wanted. How much of a difference is there between Job’s longing for a judge between God and man and Isaiah’s “He took our sickness and bore our infirmities.” The perfect longing is the perfect prophesy. “God is whatever it is better to be than not to be,” claimed Anselm. The inspired intellect of the prophets simply expressed what was better.

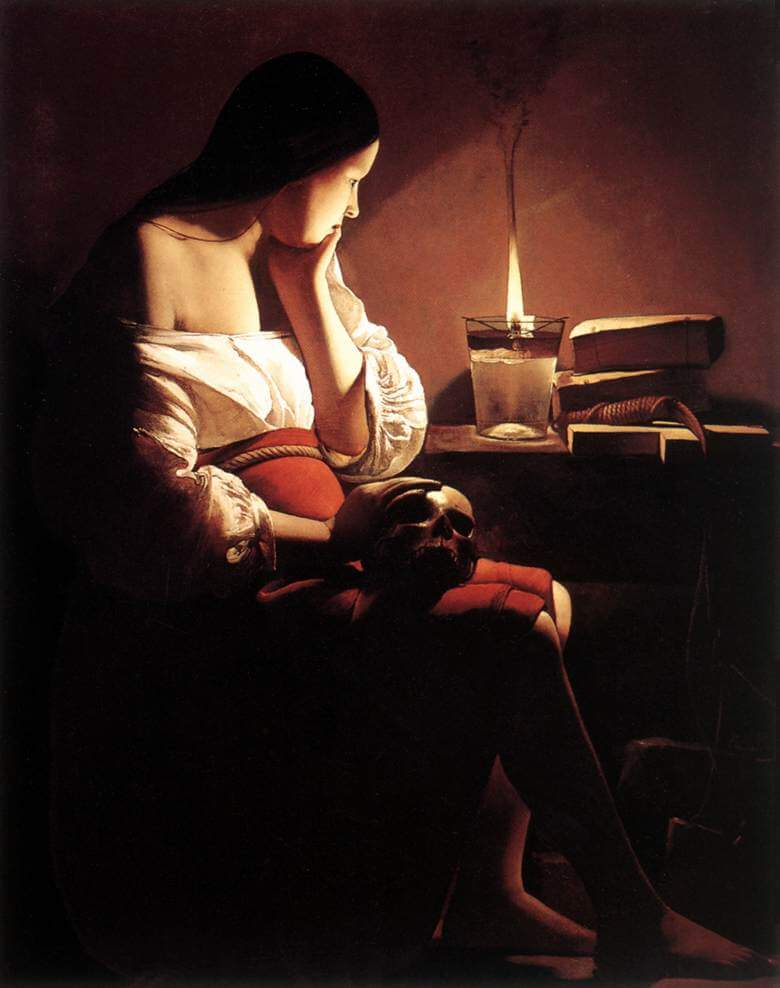

Christ could not fulfill all prophecy, all longing, unless He was first a student of man, learning the desires of man. Christ learns from the last of the prophets, the greatest man born of a woman, and so learns from the most human of human desirers. As an office occupied and fulfilled by Christ, the office of student is divine, honorable. To undertake the work of a student is to undertake the work of God, and not merely to prepare to do the work of God in some labor later in life. The teacher-as-student must learn the greatest and deepest wants of the students, as well, in order to serve as Christ served. Too often, the role of student is reduced (in the imagination) to a series of benign, necessary, inevitable tasks, and the students themselves do not approach their education with a regard higher than that which attends any other expensive thing their parents have paid for. We would do well to ask our students about other holy offices. What makes a priest special? What makes a king special? How must a priest or a king habituate themselves to self-respect? Why should a student not become habituated to such self-respect, as well?

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.