Bring Back Boethius – or, Why Music’s in the Quadrivium

Long ago there lived a people who believed the world was made of music. Above them the skies sang, and within them melody knit their marrow to their souls. So, hearing harmony in the both the world without and the world within, they created their own music to echo it. Through the art of composition, they transposed intangible universal laws into realities grasped by human senses. These people were the medievals, and they believed in the harmony of the spheres—a cosmology that, for them, had the same explanatory power that the solar system does for us moderns.

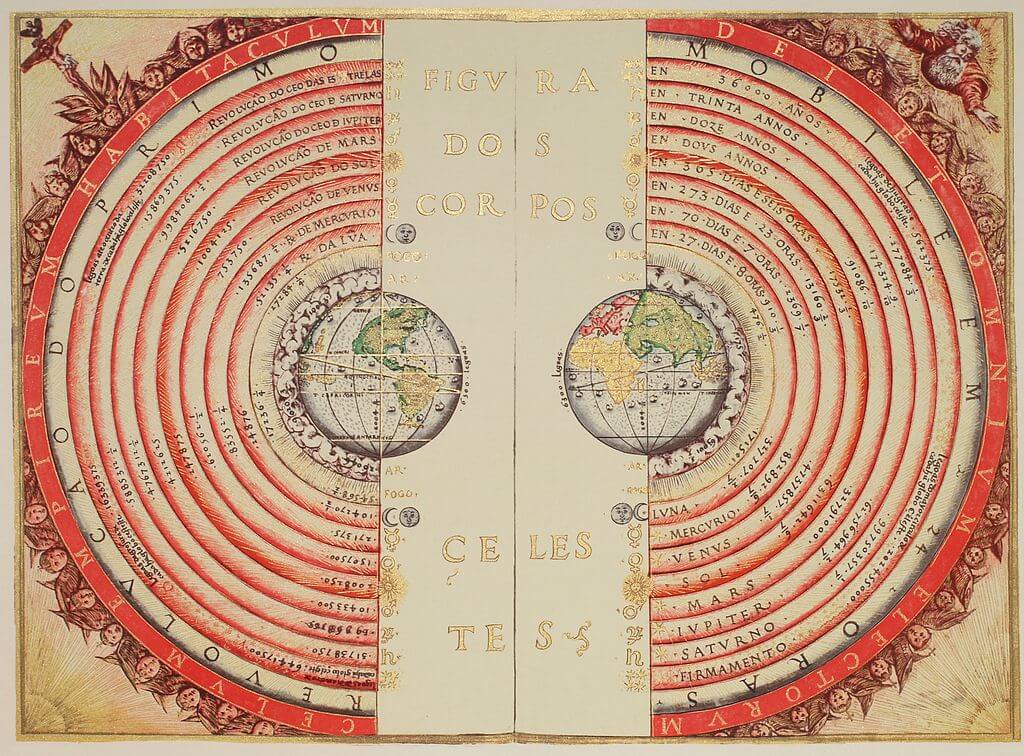

Codified by Boethius in De Institutione Musica around the year 500, this cosmology classed music into three kinds: musica mundana, the music made by the rotations of the heavenly bodies’ concentric spheres; musica humana, the harmonies holding together man’s body and spirit; and finally, musica instrumenta, the music made by man in imitation of the former two. Boethius affirmed that the first two kinds of music, though real, are inaudible to humans. But their laws of proportion and harmony could be deduced through careful study of creation; and these laws then formed the basis of medieval music theory, allowing the heavenly music to be transposed for human ears.

If you have ever been puzzled about why music belongs in the quadrivium with the maths and sciences rather than in the trivium with the arts of expression, then here you have your answer. For the medievals, music was emphatically not a means of self-expression. Rather, believing the world to be quite literally composed of music, medieval educators included music among the four disciplines devoted to understanding (rather than communicating) truth. Medieval minds understood and studied the world, and themselves as part of it, through music.

Only rarely do people arrive at correct ideas by incorrect means; yet it does happen. And it seems that the medieval music theorists’ very wrong idea about cosmology led them to a very right intuition about musicology. For although the harmony of the spheres does not exist as they conceived it, yet its principle is true: music incarnates fundamental properties of the world. The intricate relationships between math and music, the parallels between musical and literary structures, the metaphors music provides for theology, and other such correlations hint that beneath them all lies a deeper reality shared in common, beckoning further exploration.

Of all people, classical educators should be the ones to answer the beckons. And to some extent, this has happened. Many classical schools boast vibrant music programs, and classical curriculum developers are beginning to rediscover the quadrivium now that the trivium has been so successfully embraced. But it is not merely “more music” that will solve the problem. As moderns, we face a greater block to approaching music classically—a great historical and ideological gulf.

History has taken us far from the medieval mindset. Between us intervened the Enlightenment thinkers, who began to separate the disciplines of science and music. To them, these were not complementary ways of studying similar truths, but different disciplines addressing different subjects by different methods. Then the Romantic artists divorced music from the external world, using it to express personal emotions rather than to portray the ordered cosmos.

We moderns have inherited this fragmented, self-referential understanding of music. By default, we consider art as a form of self-expression, thus favoring abstract painting and poetry built on private imagery. We segregate fine art from common appreciation. We use music as a soundtrack for our lives without seriously considering that it shapes our lives, that it forms our emotions as much as expresses them. We class music as an extra-curricular activity in the schools, rather than a core-curriculum approach to studying the world.

But medieval musicologists and the classical tradition summon us to recover something of the idea of the musica mundana—to regain the sense that music can express the world as well as the self, transcendent as well as immanent realities, and that through it we may pursue and understand truth.

What would this look like? Better asked, what would this sound like? More great music being heard alongside great books being read? Serious study of the mathematics of music theory alongside algebra and geometry? Readings in music history as well as world history? Charlotte-Mason style composer studies? Adding Boethius’ De Institutione Musica to the curriculum that already includes The Consolation of Philosophy? Weaving musical metaphors into our lectures and discussions?

What precisely and practically this means must yet be discovered. Contemplating the harmony of the spheres will not recreate a world so beautifully harmonized as the medievals’ was; but perhaps it will reveal that our own world is not so atonal, so dissonant, as we who listen carelessly believe. The world sings yet: day unto day still utters speech, and night unto night reveals knowledge.

Lindsey Brigham Knott

Lindsey Knott relishes the chance to learn literature, composition, rhetoric, and logic alongside her students at a classical school in her North Florida hometown. She and her husband Alex keep a home filled with books, instruments, and good company.