The Brilliance Of Chekhov Began With His Toys

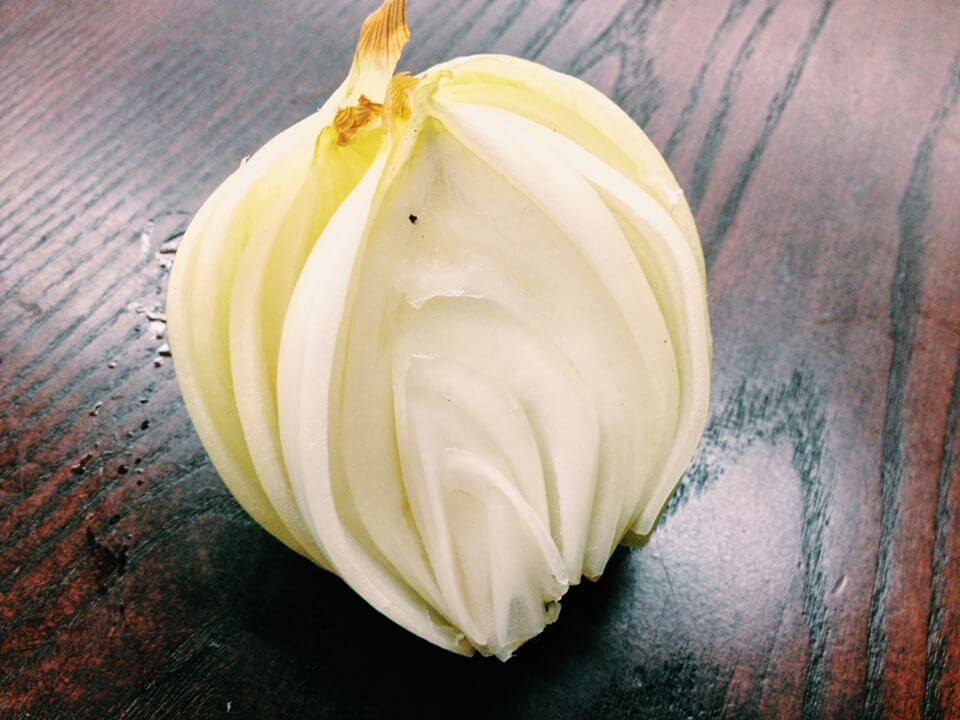

This morning a colleague and I lead our Theological Aesthetics class through the task of cutting up an onion after the fashion Robert Farrar Capon commends in The Supper of the Lamb. It took an hour.

As we were cutting the onions up, and as my colleague Jim Watkins was reading the second chapter of The Supper, I was reminded of Anton Chekhov’s “The Lady With The Little Dog,” which I taught several weeks ago. As I took all the “vectors” (as Capon calls them) out and begin sliding them back together, I recalled the terrifying conclusion of Chekhov’s hero as he walks to the hotel where his mistress is waiting for him:

He talked, thinking all the while that he was going to see her, and no living soul knew of it, and probably never would know. He had two lives: one, open, seen and known by all who cared to know, full of relative truth and of relative falsehood, exactly like the lives of his friends and acquaintances; and another life running its course in secret. And through some strange, perhaps accidental, conjunction of circumstances, everything that was essential, of interest and of value to him, everything in which he was sincere and did not deceive himself, everything that made the kernel of his life, was hidden from other people; and all that was false in him, the sheath in which he hid himself to conceal the truth — such, for instance, as his work in the bank, his discussions at the club, his “lower race,” his presence with his wife at anniversary festivities — all that was open. And he judged of others by himself, not believing in what he saw, and always believing that every man had his real, most interesting life under the cover of secrecy and under the cover of night. All personal life rested on secrecy, and possibly it was partly on that account that civilised man was so nervously anxious that personal privacy should be respected.

How was Chekhov capable of delving so deeply into the minds of his characters? I regularly ask myself this while reading his short fiction. He seems to pass through layer after layer of desire until he nearly approaches the very core of their beings, the singularity of their wills, the unifying principle of their souls. The Russians had a unique capacity for such depth which I am hard-pressed to discover in the best Western writing (Herman Hesse excepted, perhaps).

Fitting the vectors of my onion back together reminded me of the matryoshka doll, the iconic Russian dolls-inside-of-dolls. Imagine playing with such a toy from your youth. The Barbie doll is simply breasts-legs-hair. A GI Joe is nothing more than a toy gun delivery service. But the matroyshka doll points towards the soul, what St. Paul calls “the inner man.” The matryoska doll is the inner man inside the inner man inside the inner man. How could Chekhov not see man as layers inside of layers? And does the matryoshka doll not immediately invite our desire to look below the surface? To peel back the surface and discover what is hidden? Does the matryoshka doll not egg us on to look deeper? And every time the doll opens unto another doll, are we not amazed at how small they get? Do we not say, “Certainly this is as deep as it gets,” only to find another egg shaped woman inside? The point of the matryoshka doll is to taunt us with mere appearance, to disatisfy us with the surface.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.