Apart From Dogma, Inspiring Wonder Is Reckless

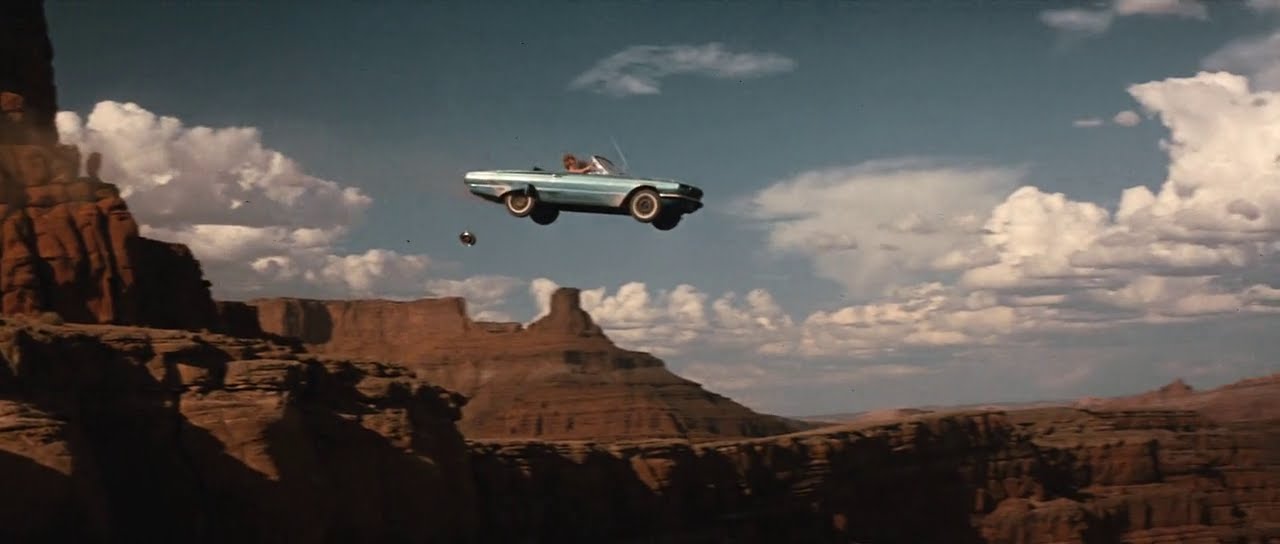

Classical educators like myself frequently talk of inspiring wonder and “irrigating deserts,” which is all well and good, but unless students understand that wonder must take place within the boundaries established by traditional Christian dogmas and creeds, inspiring wonder is reckless. Children need room to play, but inspiring wonder without also teaching that some things aren’t up for debate is like loosing little children to explore, create, and discover on a busy interstate.

A rather astounding number of Christian high school graduates go on to abandon the faith in college. Is this for lack of wonder or lack of orthodoxy? Both, I suspect.

Students brought up in fundamentalist homes and churches may find college a place where— at last— the world is not constantly reduced to purely moral concerns. As Lewis argues in “Man or Rabbit,” morality is indispensable, and yet Christianity’s greatest concern has never been mere morality, but piety, holiness, and theosis. Students who encounter the idea that there is something beyond right and wrong in college will intuitively feel the claim is true, although secularists are apt to tell Christians that the thing beyond right and wrong is simply power, which is a soul-crushing idea that leads to a life of constant bitter resentment.

At the same time, students brought up in self-styled sensitive, artistic homes and churches may find college a place where their free creative spirits first encounter the inflexible spines of dogmatists who teach all manner of fundamentals and creeds, albeit Marxist ones. Students must be raised to believe that some things are up for debate and that some things are not. Creativity and orthodoxy need one another like body and soul need one another.

Simply put, wonder is not always good. Children need time to play, but not time to play doctor. Healthy children are trained against some forms of play, and creative teenagers need to be trained against some forms of wonder. “I wonder if God is a woman,” and, “I wonder if there are actually four persons to the Trinity,” and, “I wonder if some races are naturally inferior to others,” and, “I wonder if morality is relative and gender is an oppressive social construct” are not helpful, productive things to wonder. Upon reading this, I suppose some educators will respond, “But you don’t want to just shut down students who ask,” although I hope the same educators would just shut down a toddler’s wonder in a hot stovetop or the effects of jamming a butter knife into a light socket.

I am not suggesting the student who asks, “Is it possible there is a fourth person in the Trinity?” needs to be yelled at, reprimanded, expelled, or even so much as given a stern look. However, I am suggesting that the appropriate answer to such a question is not, “Wow, interesting, right? Let’s all spend a moment mulling over Braxton’s question,” but rather, “No, church tradition has already settled the matter.” A lengthy explanation of church tradition may follow, but the explanation is offered as the correct answer to the question, not “one way of looking at it.” Free play is good for kids, but only as long as they are not free to play some things. Unhinged imaginations always work their way around to perversity.

Educators who worry that dogma will turn students off simply aren’t paying attention to what happens in secular colleges, where many Christian kids encounter dogmatism for the first time and absolutely love it. People who are willing to say, “You’re dead wrong,” are really compelling, especially if you’ve never seen one face to face. Besides, so many Christians now grow up in environments where appeasing secularist tastes and flattering secularist values is demanded, it’s entrancing to finally meet someone with unyielding confidence in their own ideas.

At the same time, educators who worry that all the wonder in the world won’t lead to a good job need to consider how many people with good jobs commit suicide every day. A good life demands both dogma and wonder, work and leisure, fences and freedom. Every school ought to assess its curriculum, architecture, décor, pedagogy, and staff along these lines. By itself, inspiring wonder is not enough. By itself, teaching dogma is not enough.

In the same way inspiring wonder is not a task for just one teacher in just one class, teaching dogma is a responsibility all teachers must share. As the author of a book on the subject, allow me to suggest that beginning class with the recitation of a catechism is a good way of showing students where the fences are which they must not leap. Once students know what things are not up for debate, they have a clear picture of what is, and the conversation can profitably begin.

Joshua Gibbs

Joshua Gibbs teaches online classes at GibbsClassical.com. He is the author of How To Be Unlucky, Something They Will Not Forget, and Blasphemers. His wife is generous and his children are funny.