Anatomy of Things Unseen

We had been practicing the common topics of rhetoric for several weeks when one of the students approached me after class, brow furrowed. “Miss Brigham,” he confided, “these things are messing with me.”

(My teacher’s heart rejoiced within me. If “things messing with me” means assumptions and desires being displaced, upended, rearranged, then surely this is an excellent—albeit colloquial—definition of learning itself.)

But all I said was, “Really? Why’s that?” And the student explained how, as we’d been studying the topics, he had begun to notice them amidst every casual conversation. He would be jolted by the recognition of definition in a debate amongst friends, or relationship at the center of a family discussion, or comparison in the making of a decision. And the uncanniness of this unsettled him—made him feel programmed or something.

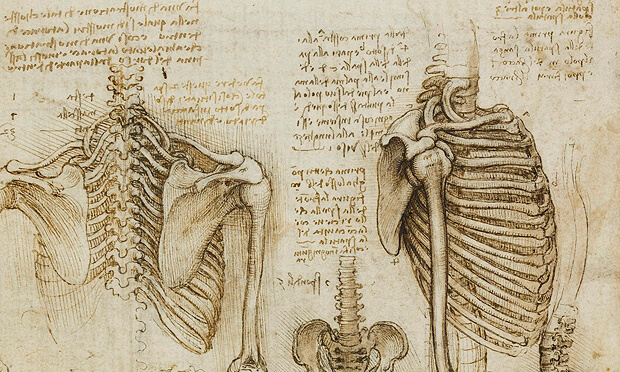

It was not a reaction I had expected, but the more I consider it, the less surprising it seems. Picking up on a phrase in Edward Corbett’s trusty rhetoric text, I have presented the common topics to my students as an “anatomy of thought.” The five common topics—definition, comparison, relationship, circumstance, and testimony—more or less comprehensively categorize the patterns of human thought, much like the various biological systems in an anatomy textbook categorize the processes of the human body.

But the topics “mess with” my students because the idea that thought has an anatomy fits poorly into twenty-first century assumptions, which associate anatomy with the tangible world and regard thought as something vague and amorphous.

Think of it this way. Today’s students learn to name and number, in painstaking detail, the anatomy of their own bodies: skeletal system, muscular system, nervous system, digestive system—and the list goes on. A medieval student, by contrast, would learn that the human body is a combination of four humors, about which not too much more could be said. But the ranks of angels—now that could be anatomized! The four cardinal virtues—these could be clearly delineated, as could the three theological virtues, and all their corresponding vices. The heavenly spheres could be diagrammed, and thought itself systematized into tidy topics.

The curricular contrast indicates a much deeper difference in understanding. Ancient and medieval thinkers perceived the immaterial world as bearing an equal or greater weight of reality than the material world. Nowadays, however, we tend to see the material world in high relief, while the immaterial world hovers as a nebulous mist in our peripheral vision. And the difference in understanding shapes drastic differences in action.

Because we discern order and pattern in the material world of earth and bodies and physical forces, we predicate the laws of causation and recognize our ability to predict and manipulate material things. But, because we do not discern order and pattern in the immaterial world, we consider it unpredictable and ourselves helpless within it. We judge feeling to be the only authentic basis for belief and action, and we assume that feeling is utterly spontaneous and ungovernable—making our belief and action spontaneous and ungovernable, too. As a result, we have developed a vast capacity to manipulate the material world, while atrophying in the power to direct our own souls.

Again, this assumption has revealed itself in my students’ reactions to the common topics. Studying circumstance, we considered the following proposition: If someone has the power and the desire and the opportunity to do something, then he or she will do it. This, too, “messed with” students. They seemed to think it fatalistic or mechanistic, conflicting with their understanding of human responsibility and choice. But, as we contemplated each element of the proposition, their eyes began to light; and when we applied it in to the particular, personal problem of fighting temptation, they spoke with excitement and wonder. To many students—to many of us!—temptation seems irresistible. And, if you have accepted the assumption that feeling directs action, then indeed it cannot be denied: temptation is, by definition, the allure of something you desire.

But if all action, including response to temptation, is compounded of power, desire, and opportunity, then there is hope against temptation. Sanctification is the gradual strengthening of our desire to be conformed to Christ over against our desire to submit to temptation; this strengthening of desire is often accomplished through the discipline of limiting our opportunities to sin; and it is done in the hopeful anticipation of a state of glorification, in which our very power to sin will be eclipsed.

My students reacted with wonder because, all of a sudden, they could perceive some pattern in the immaterial world which would free their souls to be agents within it. This freedom is, originally, what the “liberal arts” were intended to accomplish; this is the gift that our illiberal culture denies us. We learn to name every bit of bone and blood and nerve in our physical bodies, but our own minds remain to us a mystery. We fixate on the physical and give nary a thought to the anatomy of things unseen.

Perhaps, then, we ought to seek every opportunity to teach this in our vocation of teaching. Whether by teaching the common topics, or speaking of virtue, or contemplating the principalities and powers and rulers of this age—we can “mess with” students’ minds for the sake of freeing their souls.

Lindsey Brigham Knott

Lindsey Knott relishes the chance to learn literature, composition, rhetoric, and logic alongside her students at a classical school in her North Florida hometown. She and her husband Alex keep a home filled with books, instruments, and good company.