Why We Publish (and Love) Joshua Gibbs

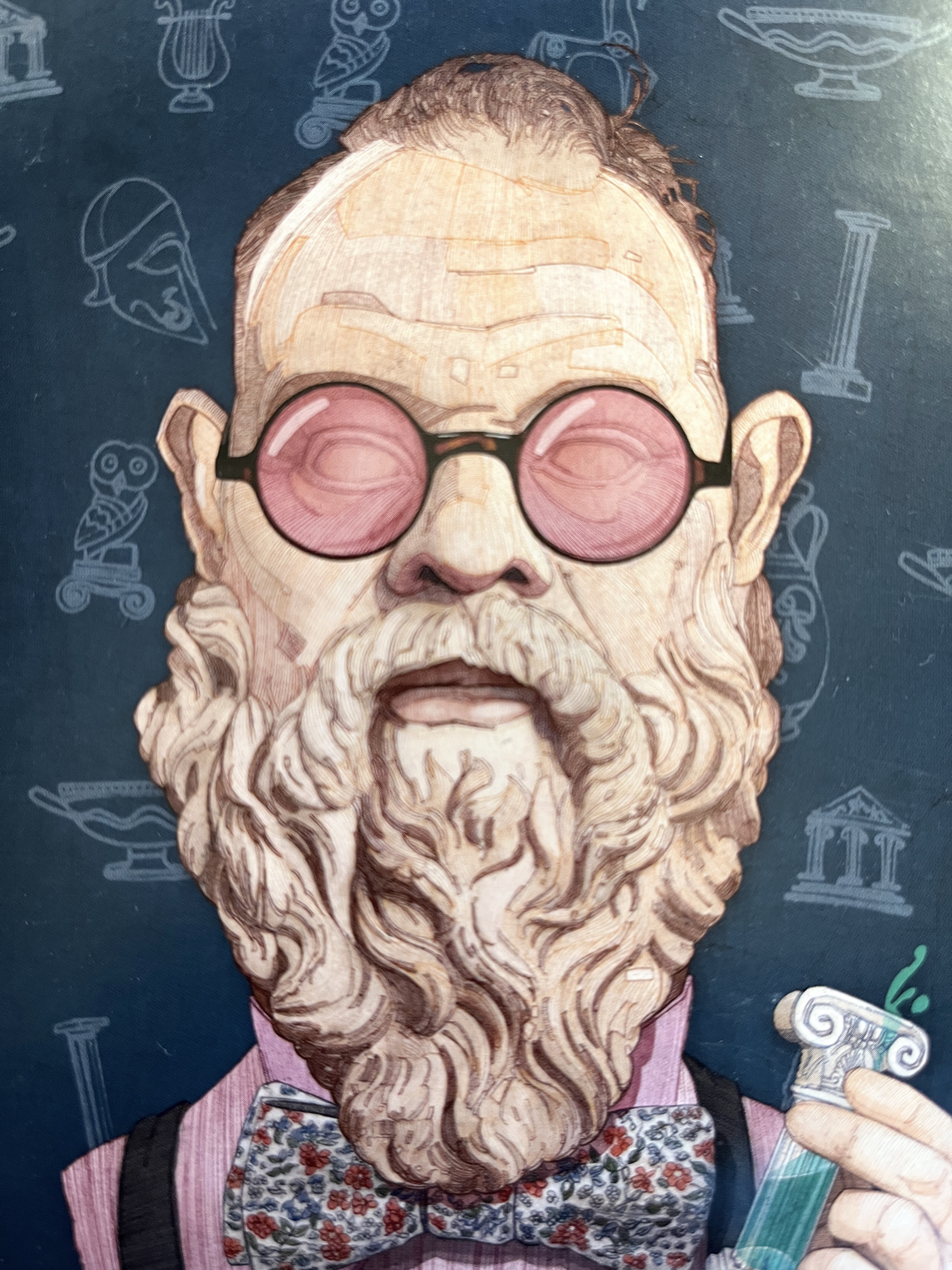

Anyone who has been around the CiRCE website or social media long enough knows that one of our most prolific and popular and controversial writers is the inimitable Joshua Gibbs, the man whose beard is an emblem of his writing. His beard is as long as a list of his contributions, and his contributions are—often—as knotty as his beard. It doesn’t happen very often, but every once in a while a post of his will spark some controversy in the world of social media that inevitably leads someone to comment, “Come on, CiRCE. Do better!” If you are a regular reader of Joshua Gibbs’ posts and haven’t heard this reaction before, then you must be one of the happy few people who still live on this earth without having succumbed to the pressure of being connected via social media. Lest I come across as thinking of Joshua Gibbs as an unappreciated provocateur, let me add that these responses are rare. It’s just that when they do happen, they happen.

Perhaps this is why we feel the need to write a post describing, explaining, and even justifying why we continue to publish and love Joshua Gibbs. It won’t change anyone’s mind who has already decided he loves him or he hates him. It may, however, help others to understand our desire for the CiRCE blog, and possibly even to understand Josh’s own rhetorical style. CiRCE publishes and loves Joshua Gibbs for three reasons. Well, we love him for a lot of reasons (he’s the image of God, Jesus tells us to, and he has a great beard) but three reasons are apropos to the topic at hand.

The first reason we publish and love Joshua Gibbs is that he is a purveyor of wisdom and common sense, and that takes courage. In a world that rejects the obvious and common sense, it is a courageous person who is willing to state it. We are surrounded by people pretending to see the emperor’s beautiful clothes, and we desperately await the small child who will be courageous enough to tell us he’s naked. The tall man with thick glasses and a long beard is willing to be that child for us. So we welcome him and do our part to amplify his voice. And the child tells the emperor and those around him the truth without qualification. He tells us “The emperor has no clothes,” not “The emperor has no clothes to me!” The poor child of the fairy tale lacks the humility demanded by a society as refined and advanced and progressive as ours to qualify his statement properly. Rather than saying, as we would today, that “It seems to me, at least from my perspective, I think, that the emperor might not have any clothes on, though I’m not really sure,” he says plainly and baldly, “The emperor has no clothes.” Some occasions do demand, of course, qualification and “nuance,” just not as often in a world that has turned nuance and exceptions and extremes into norms as we might think. Without wisdom, the qualification, nuance, exception, or extreme becomes just the excuse this world needs to twist the truth to justify its own selfish desires.

We also publish and love Joshua Gibbs because he is proverbial. The host of “Proverbial” embodies what he knows. He is willing to imitate Proverbs and other wisdom literature even though our world cannot accept wisdom expressed so universally and dogmatically. The Christian can read Proverbs and understand, usually, their “proverbial” nature. But, write something with a proverbial rhetoric today in a blog post and share it on social media, and you’ve almost certainly started the proverbial dumpster fire. Solomon tells us, in Proverbs 23, “When thou sittest to eat with a ruler, consider diligently what is before thee: And put a knife to thy throat, if thou be a man given to appetite.” We read that, and we get it. No Christian has ever sat a dinner with me and put a knife to his throat while eating—though that may have to do with me not being a ruler. When Christ tells us to pluck out our eye or cut off our hand, we get that he is speaking in a proverbial manner. In fact, what each of them is trying to do is use an extreme solution to draw the appropriate amount of attention to something the world has been desensitized to. Gluttony and lust are serious sins that they, we, are desensitized to. We need extreme demands set before us to wake us up to their dangers. If Christ hadn’t asked me to cut off my right hand, I might never have even considered that merely looking at a woman to lust after her was as dangerous as it is. To speak proverbially is to speak in a way that forces us to engage in the discussion genuinely. We fail to respond proverbially, however, when we change discussion from the reality of the sin (or problem) to the so-called ridiculousness of the solution. If gluttony is the problem, I need to do something about gluttony, not criticize Solomon for giving me an unrealistic, unfair, or unlikable solution.

Finally, we publish and love Joshua Gibbs because he is dialectical. The man thinks about and sees things from perspectives our world rarely does. Does this mean he sees it from every perspective, or that he sees it always from the right perspective. Not necessarily. Not even likely. However, the very fact that he brings another perspective means he brings a perspective that differs from mine. This perspective becomes a perspective that enters into a dialectical relationship with my own limited perspective. If I can engage them both properly, I become better at seeing and thinking myself. I may even arrive at a greater understanding of the truth through this dialectical process. We, as parents, spouses, neighbors, Christians, Americans, classical educators, need to engage in the dialectic. It is how we ourselves grow in wisdom and virtue. It is, as Socrates taught us, the means to drawing toward the Truth. Any unwillingness to challenge our ideas, our opinions, our understanding of the truth, prevents us from refining and furthering our understanding of the Truth.

We are thankful for our friendship with Joshua Gibbs. We are thankful for the voice he brings to the classical education renewal because it is a voice of wisdom and common sense, it is a proverbial voice, and it is a voice that provokes the dialectic. It is not CiRCE’s voice, but that’s the most important part of it. CIRCE too needs to be challenged with direct statements of common sense, with proverbial wisdom, and with dialectical challenges, so we publish Joshua Gibbs because we need that challenge. We love it when we agree with him, and we love it when we do not, because in both cases we’ve invited opportunities to grow in wisdom and virtue.

Dr. Matthew Bianco

Dr. Matthew Bianco is the Chief Operations Officer for the CiRCE Institute, where he also serves as a head mentor in the CiRCE apprenticeship program. A homeschooling father of three, he has graduated all three of his children, the eldest of whom graduated from St. John's College in Annapolis, MD. His second and third both graduated from Belmont Abbey College in Charlotte, NC. He is married to his altogether lovely high school sweetheart, Patricia. Dr. Matt Bianco has a PhD in Humanities from Faulkner University's Great Books Honors College and wrote his dissertation on Plato's Republic and education. He is the author of Letters to My Sons: A Humane Vision for Human Relationships.