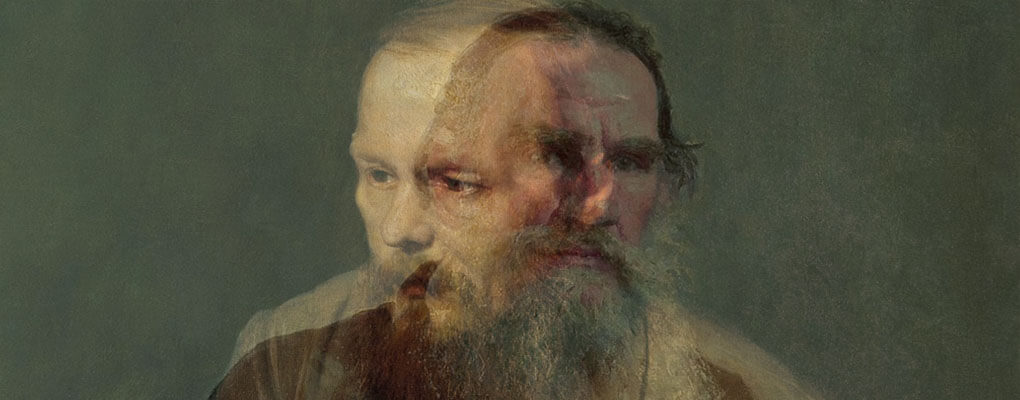

Why Tolstoy and Dostoevsky Matter Now More Than Ever

When friends ask me what my favorite novel is, I tell them, “That’s easy. Crime and Punishment. Or Anna Karenina. Depending upon which one I read last.”

As a teacher at a great books college, my job demands much reading of literature. It is a task I happily embrace. Accordingly, I have read many of the classics of the Western canon. And, after all that reading I am convinced that for power of psychology, for characterization, and for theatrical tension, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy count among the greatest writers in the canon.

Furthermore, these Russians matter more than ever today. Both foresaw a creeping utilitarian ethic that would warp the social life of Russia and eventually dominate the conceptual framework of Western citizens.

Dostoevsky and Tolstoy were both born in Russia, seven years apart. Despite never meeting, each held the other in deep esteem. Dostoevsky called Tolstoy “the most beloved writer among the Russian public of all shades.” The last book Tolstoy ever read before he died was Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov.

The two authors shared an era and a country, but they lived in different sectors of Russian society, and offered profoundly different visions as artists.

Dostoevsky loved Russia’s underbelly — the gamblers, the prostitutes, the street-revolutionaries. His pace is frantic with anxiety and his scenes resemble the best of theatre-drama — a barely domesticated violence of words.

Both foresaw a creeping utilitarian ethic that would warp the social life of Russia and eventually dominate the conceptual framework of Western citizens.

In Crime and Punishment, he sets his anti-hero Raskolnikov in the seedy streets of St. Petersburg. Raskolnikov walks these streets seeking to cleanse his mind of murderous inclinations. Yet in the streets he witnesses children begging, rumors of suicide, and gutter-drunks; these visions spread more disease through the tender tissue of his soul. Overwhelmed by the street, Raskolnikov dives deeper into murder-planning.

Dostoevsky’s greatest characters don’t just think ideas, they feel ideas. “His unrivaled genius as an ideological novelist,” wrote Joseph Frank, “was this capacity to invent actions and situations in which ideas dominate behavior without the latter becoming allegorical” (Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time, 2009).

Raskolnikov is a classic Dostoevskian character; he swings wildly between the elation of Christian hope and the suffocating weight of utilitarian ethics. From the first pages of Crime, Raskolnikov is planning. As the events unfold, his plan is revealed as the murder of a lowly pawnbroker. But it will be no ordinary murder; it will be a philosophical murder. Raskolnikov internally justifies his plan by creating a “transvaluation of values” (the phrase is Nietzsche’s) that actually demonstrates that the murder is appropriate. The haggard, hoarding pawnbroker had no utility, no value. But Raskolnikov, as a man unafraid to “step across the line,” is of great value. Thus, Raskolnikov is justified to destroy her and benefit from her hoarded rubles.

Yet moments after planning the murder, he is filled with deep compassion for the meek and mentally undeveloped Lizaveta, the pawnbroker’s sister. Lizaveta also lacks “value”, yet Raskolnikov laments that her innocence is harmed by his murderous plan.

A violent inner battle ensues. Power and compassion each vie for Raskolnikov’s heart. His young memories of Christian hope clash with the utilitarian impulse of his Russian adulthood. This battle mirrors a broader dilemma facing the 21st-century West. Dostoevsky feared the abandonment of Christian ideals and rebuked Western Europe for discarding hope in a “salvation that came from God and was proclaimed through revelation — ‘Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself’ — and replaced it with practical conclusions, such as, ‘Chacun pour soi et Dieu pour tous’ [‘Every man for himself and God for all’].”

Like Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy also worried about the disintegration of spiritual convictions in 19th century Russia. The battleground of his debate was not Dostoevsky’s sullied streets, but the thick-carpeted hallways of the aristocracy. Tolstoy’s aristocrats leap between affairs of family, business, and romance without genuine brotherly love or existential commitment.

Against this spiritual torpidity, Tolstoy discovers individuals enduring real spiritual crises. He finds Anna Karenina who, while returning by train from counseling her sister against divorce, exchanges glances with the man who will later help unravel her own marriage.

When Anna attends a party of socialites, we meet Levin — a thinly-disguised version of Tolstoy himself — who plans to propose to Anna’s sister-in-law, Kitty. Unfortunately, Kitty loves Vronsky and rebuffs Levin’s advance.

Rejected by Kitty, Levin leaves the city and doesn’t see her again for months. When finally they meet again, Tolstoy offers a chapter (iv,13) that is a mini-masterpiece within the novel’s grand tableau. Levin and Kitty play a word-game on a card table. Using word-blocks, Kitty apologizes to Levin using initials: t, y, c, f, a, f, w, h. “That you could forgive and forget what happened.” To this Levin replies, “I have nothing to forgive and forget, I have never stopped loving you.”

Tolstoy’s famous opening line, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”, perfectly captures the action of Anna Karenina. Levin and Kitty’s frustrating-yet-enchanting romance demonstrates that “happy families are all alike” even as Anna’s collapses in its own way.

In the end, Anna’s former friends reject her as a disgraced woman and she returns home — only to find her swashbuckling Vronsky cold, distant, and distracted. Her doom is near.

It is rumored that Tolstoy began writing a novel against divorce, but discovered such sympathy for Anna that he shifted his critique to Russian society. His inscription from Deuteronomy and Romans seem directed, less at Anna’s hot-heartedness, but at her society’s calloused rejection: “Vengeance is mine, I will repay.”

Both Tolstoy and Dostoevsky were deeply shaped by the Christian scriptures. The book of Job, in particular, affected Dostoevsky. As an adult, he reread the book of Job which thrust him into a state of “unhealthy rapture”. “It’s a strange thing, Anya,” he wrote his wife in 1875, “this book is one of the first in my life which made an impression on me; I was then still almost a child.”

Both novelists obsess over eternal questions — giving their work a fresh relevancy in our culture preoccupied with an ethics of utility.

Dostoevsky’s characters, like Job, were stripped bare of the social normalities that lent an ease to everyday life. He thrust characters like Raskolnikov into a crucible of faith and doubt that he himself experienced throughout his life.

Dostoevsky, a former prison-inmate, was blessed and cursed with the fiery psychology of the artist-philosopher. While 18th and 19th century philosophers loudly rattled their buckets of chilly syllogisms, Dostoevsky replied hotly with unforgettable characters and violent plots. He did not philosophize about atheism or theism; they clashed within his belly and emerged in his novels. All of his mature novels address the psychic and social ramifications of the choice between Christianity and atheism. For example, his “The Grand Inquisitor” (a chapter within The Brothers Karamazov) is a world-classic treatment of the question of why God permits evil.

Spiritual crises also preoccupy the novels of Tolstoy, who, in the middle of his life, endured a profound inner crisis. The last chapters of Anna Karenina articulate Levin’s inner groans about the meaning of life. These groans resemble the crisis that Tolstoy would later document in My Confession (1880). Indeed, so bad were Tolstoy’s bouts of despair that he asked his wife to hide his hunting rifle lest he use it on himself while walking his dogs.

Emerging from this crisis, Tolstoy gave up meat, smoking, hunting, and his copyrights; he preached pacifism, anarchism, and a deeply personal Christianity.

Strict traditionalists will scold the theology of both novelists; the Russian Orthodox Church excommunicated Tolstoy in 1901 for (among other reasons) rejecting the biblical doctrine of bodily resurrection. And Dostoevsky’s nationalistic eschatology is difficult for any non-Russian to embrace.

Nevertheless, Christianity was “the dominating force” in the works of both novelists (William Lyon Phelps, Essays on Russian Novelists, 1911). Both knew something neglected by the best of modern novelists: The human heart inhales hope for transcendence. Both novelists portrayed their heroes and heroines as wandering hearts, unprotected by doctrinal armor, exposed to the same tribulations and rewards that God visited upon Job. Both novelists obsess over eternal questions — giving their work a fresh relevancy in our culture preoccupied with an ethics of utility.