Tune My Heart: Part 2, Handel’s “Messiah”

“Handel is the greatest composer that ever lived . . . I would uncover my head and kneel down on his tomb.” —Beethoven quoted by Edward Schulz, “A Day with Beethoven,” The Harmonicum (1824).

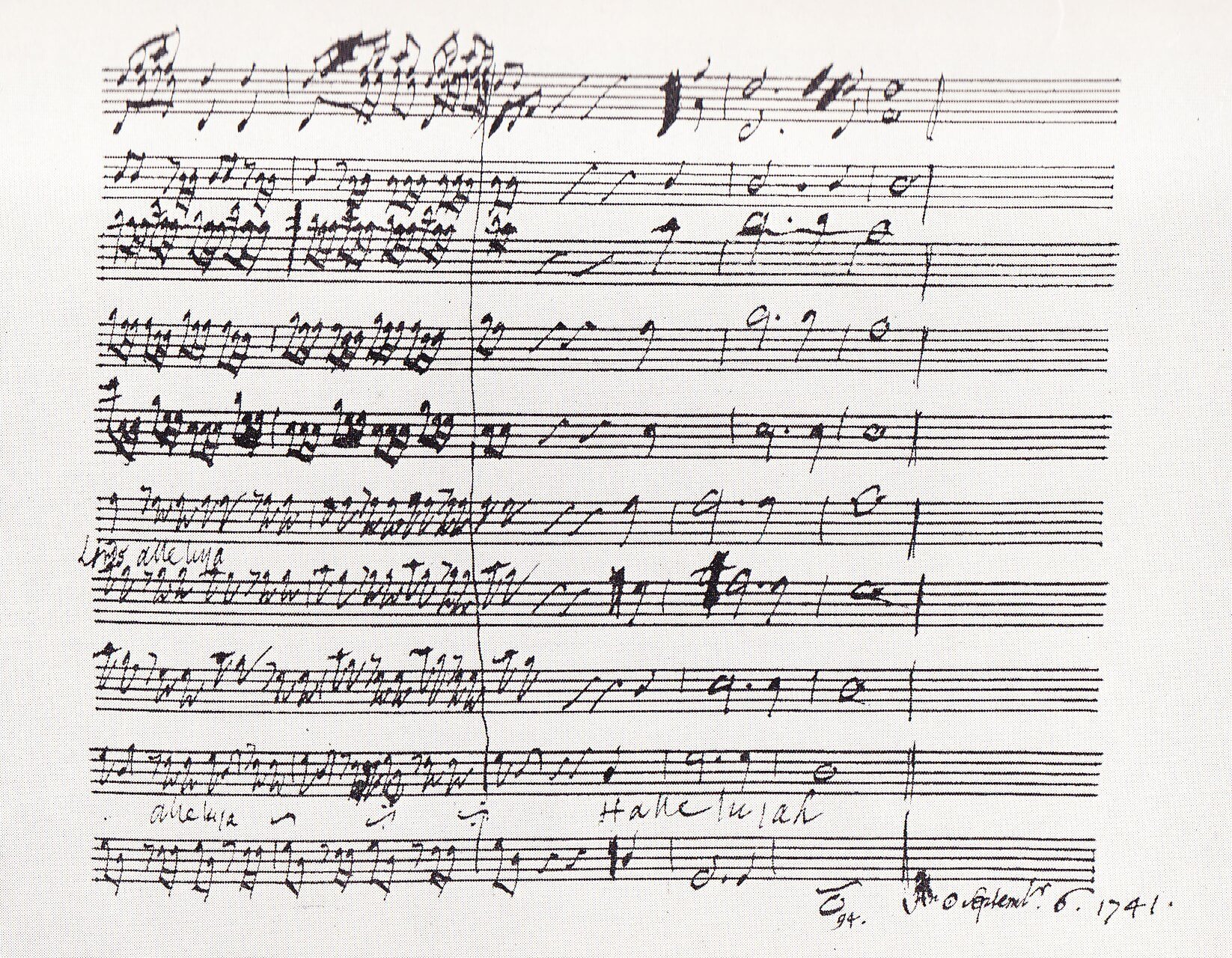

This Advent season, our family chose to guide our own musical consumption with three beloved Advent classics that merit and reward our attention, the second of which is Part I of Handel’s Messiah. Handel and other Baroque composers (Bach, Purcell, Monteverdi, Vivaldi, Scarlatti) are considered the ultimate masters of musical composition, and their works can be incredibly dense and complex. The more we listen to Baroque music, the more we understand that framework in which it operates and the easier it becomes to identify and appreciate the masters.

Perhaps one of the greatest gifts you can give yourself (and your family/ students) is to learn how to identify and enjoy good music. This is not an easy task, especially with a common but false belief in the complete subjectivity of music. When we discuss music in our classes, even among the classically educated and musically trained, it often takes a lot of questioning and dialectical conversation to get students to abandon the postmodern hogwash that there is no such thing as good or bad music and that beauty is in the ear of the listener. The pivotal question is often something like, “Is there really no one willing to admit that bad music exists?” Then the students gradually begin to express distaste for certain music, and their defenses give us something to work with. We begin to draw the veil on the masterful way in which the music of their movies, games, and albums utilizes and demonstrates the very objective nature of music.

No one understood this nature better than the composers of the Baroque era. They wholeheartedly espoused the Greek musical philosophy that certain musical techniques could evoke certain emotions. With all of the musical advancements of the Baroque era (orchestras with new instruments to arrange in countless combinations, and numerous musical forms to work with like the sonata, the opera, and the oratorio) philosophers believed that music had the power to evoke any emotion known to man. This prominent baroque philosophy is known as “the doctrine of affections.” Musical techniques were categorized with the corresponding emotion they were thought to induce. Descending melodies were bad news, and a descending chromatic line (like the bass line in “Dido’s Lament” from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas) was a very specific type of bad news: a musical harbinger of death. Handel’s understanding of these techniques was paramount. Mozart is quoted as saying “Handel understands effect better than any of us—when he chooses, he strikes like a thunderbolt.”

The many compositional techniques established in this era have continued to be used ever since. Wagner coined the term “leitmotif” for the small lines of music designed to embody and evoke a connection with specific characters, themes, or emotions. John Williams is known for his masterful employment of this tradition of techniques to create some of the most iconic themes and soundtracks in the film world. Composers who draw on these techniques can transport us from silence to a soundscape that fulfills and exceeds our musical hopes and expectations in the right proportions, guiding us to feel and celebrate whatever the composer feels and celebrates: joy, anger, romance, violence, sadness, promiscuity, etc. This gives music a powerful influence over our emotions. And we have lost the understanding of the objective nature of music and the basic ways in which it influences us. Bach and Handel gave us some of the most powerful and glorious music known to man because they understood and masterfully employed these techniques on the world’s most significant text, the Bible. Handel’s oratorio awakens within the soul the sentiments one ought to feel when hearing these passages of Scripture, infusing color and light and emotion into the text. Part I presents a compelling invitation to enter into the drama of salvation by anticipating and rejoicing in the coming arrival of the King.

The Literal

In contrast with our first piece, a lovely hymn that can be sung by anyone, Handel’s oratorio the Messiah is a towering work of musical artifice, requiring trained choral singers, soloists, and instrumentalists. The soloists sing recitatives (dramatic speech-like recitation, advancing the plot) and arias (tuneful, emotionally expressive songs). The instrumentalists open the work with an overture, and serve as the musical foundation and enhancement of the choral and solo works. The overture is followed by a series of songs with biblical texts prophesying or describing the coming of the Messiah, his birth, and the blessings of his presence. Each piece of music has a distinct character, which is generally contrasted with the previous piece. The phrases are often sequential, stating a musical theme, then repeating and restating it in higher or lower registers. The libretto set excerpts of Scripture in various arrangements, divided into five scenes:

Scene 1: Isaiah’s prophecy of salvation

- Sinfony: (instrumental)

- Comfort ye my people (tenor aria) Isaiah 40:1-3

- Ev’ry valley shall be exalted (tenor aria) Isaiah 40:4

- And the glory of the Lord (anthem chorus) Isaiah 40:5

Scene 2: The coming judgment

- Thus saith the Lord of hosts (bass recitative) Isaiah 40:4

- But who may abide the day of his coming (soprano or alto) Malachi 3:2

- And he shall purify the sons of Levi (chorus) Malachi 3:3

Scene 3: The prophecy of Christ’s birth

- Behold, a virgin shall conceive (alto) Isaiah 7:14

- O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion (air for alto and chorus) Isaiah 40:9; 60:1

- For behold, darkness shall cover the earth (bass) Isaiah 60:2-3

- The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light (bass) Isaiah 9:2

- For unto us a child is born (duet chorus) Isaiah 9:6

Scene 4: The annunciation to the shepherds

- “Pastoral symphony” (instrumental)

- (a) There were shepherds abiding in the fields (soprano recitative) Luke 2:8

- (b) And lo, the angel of the Lord (accompanied sop recit) Luke 2:9

- And the angel said unto them (sop recit) Luke 2:10-11

- And suddenly there was with the angel (accompanied sop recit) Luke 2:13

- Glory to God in the highest (chorus) Luke 2:14

Scene 5: Christ’s healing and redemption

- Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion (soprano) Zechariah 9:9-10

- Then shall the eyes of the blind be opened (soprano or alto recitative) Isaiah 35:5-6

- He shall feed his flock like a shepherd (alto/soprano) Isaiah 40:11; Matthew 11:28-29

- His yoke is easy (duet chorus) Matthew 11:30

The Allegorical

As we move beyond a simple encounter with the sound of the Messiah to a place where we can differentiate, define, and articulate the auditory images that come with the landscape of this masterpiece, the overlaying of these images upon the text begins to operate upon the mind metaphorically. As Christians listening to this piece during Advent, the literal meaning of the images is plain—the Messiah is Christ coming for His people, Israel. The allegory of the Old Testament, according to the traditional interpretation of it that Handel is operating within, is, like that of “O Come, O Come Emmanuel,” that Israel’s God is ours; the entire history of Israel is protracted to become the drama of the individual who is also part of the body of Christ. This one and many dual thematic interpretation that the Christian brings to the scriptural text is aptly imaged in Handel’s “For unto us a child is born,” where the choir seems to echo itself only to unite triumphantly in the words “Wonderful, Counselor, the Mighty God, the Everlasting Father, the Prince of Peace.” Christ comes for many, and it is that which unites Jew and Gentile as “one new man.” One cannot help but note here that the “For unto us a child is born” movement speaks as well to the perennial hopefulness that comes with each new life—certainly to Jewish mothers prior to the incarnation. God’s promise to Eve, and to all women, that there would come one who would “crush the serpent’s head” has lent a kind of hushed holy expectation to the coming of each child and generation—all finally united in Christ. While it is established that Handel sees these Old Testament passages in light of New Testament revelation, some Christian listeners may still be stumped by how “Good tidings to Zion,” “He shall purify the sons of Levi,” or “O Daughter of Zion” relate to the church. While there is not space here to unpack them all, we promise that each movement of the Messiah contains an icon/image of Christ that celebrates his coming for the one and many; Zion is both a geographic location and the symbolic place of all believers, Levi is both tribe and the universal priesthood (See Herbert’s The Altar), and the Daughter of Zion is both the race of Israel and the Church; the bride of Christ.

The Moral

The characteristics of the vocal and instrumental sound are carefully chosen to enhance the text and forge within us a deep response to and resonance with the text. In a previous class we had discussed the properties of the six basic elements of music: the melody, the harmony, the rhythm, the timbre (which instruments/voices are chosen), the texture (what combination of timbres are used) and the form. Simply naming the musical characteristics while considering the phrases they represent deepened our understanding and enjoyment of the music’s effect on us.

The French overture was an elegant opening for Baroque stage music, marked by grand, slow, double dotted rhythms in the first section, followed by an energetic fugue (1). This form fittingly draws us into the start of a grand drama. Double dotted rhythms are used predominately as expressions of a grand or royal procession. With this in mind we can envision the arrival or a king. Then its as if the king’s court begins to dance in the fugue section. Handel’s minor setting gives the whole piece a mournful, foreboding character.

The busy, thick texture of the instrumentation settles into a soft, light pulsing and a high clear timbre of the tenor announces Isaiah’s prophesy in scene 1. The long smooth phrases are fitting for the text of “Comfort ye.” The tempo and rhythmic patterns speed up during “every valley shall be exalted,” with the contour of the melodies depicting the text. This aria contrasts the setting of the fifth piece, in which each of the vocal parts of the chorus announce the glory of the Lord, sequentially rolling out the musical material of the text “shall be revealed.”

The next scene opens with the authoritative vocal sound of the bass soloist representing the voice of God coming down from heaven, using a full descending minor chord to announce the coming judgement (5). On the phrase “And I will shake,” the bass has jaggedly descending melismas (long runs) to depict the shaking. The next aria opens with smooth minor lines, giving a foreboding feeling to the text “But who may abide the day of his coming and who may stand when he appeareth” (6). Then the rhythms pick up and the melody burst into fast melismas on “for he is like a refiner’s fire.” The excitement and power of these vivid phrases conjure up the image of a consuming fire. The texture expands as the chorus continues the idea with the statement “and he shall purify,” with have fast sparkling runs on the word purify (7).

One of the highlights of scene 3 is the long, descending, oddly meandering melody of the bass singing “The people that walketh in darkness” (11). The next phrase. “have seen a great light” repeats and winds its way upward. The agitated excitement of the soprano recitative “And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host,” (16) explodes into the full choral outburst of “Glory to God in the highest” (17).

The sparkling fast runs of the soprano aria “Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion” open the last scene and exude contagious joy with continuous running exclamations of “rejoice!” Part I closes with light instrumentation and soothing gentle melodies in “His yoke is easy” (21).

The Anagogical

“Anagoge” is, in part, derived from the Greek word for “ascent” and has been used—in the sense of the word “anagogical”—to describe the mystical ability of humans to conceive of universal symbols; objects, characters, stories, and types that speak to the existence of all of humanity, not just that of the individuals. An oratorio, such as the Messiah, is an exquisite example in both form and content of such a “speaking” to the action or movement of soul. Consider the movement and text of “For behold darkness shall cover the earth” found in Isaiah 60:2 (linked here with a slower version for your listening pleasure):

For, behold, the darkness shall cover the earth, and gross darkness the people: but the LORD shall arise upon thee, and his glory shall be seen upon thee.

As one listens to the interplay of text and musical imagery, one is not confronted immediately with the prophetic implications of this passage for Israel or the church—nor do we feel moved to do anything. Instead we see, in some manner, the opening lines of Genesis 1 where God hovers over the waters of chaos and creates it anew. This primal place is within us, a chaos that we imaginatively consider, as the Lord ascends over it “with healing in His wings” (see also Hopkins’ “Gods’ Grandeur”). We each know the darkness within us, and the consideration of God’s rising upon it is an ecstatic experience.

Another example is found in the famously memorable movement “Ev’ry valley shall be exalted” found in Isaiah 40:4:

Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low: and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough places plain . . .

Again, we are not distracted with some literal flattening of the earth that is being prophesied—though perhaps God may so choose to accomplish it in the end of time; instead we sense that this is about justice. Justice, according to Socrates, is the virtue of the soul (as seeing is the virtue of the eyes), and we sense that the valleys, the hills, the crooked, and rough are places within the hearts and souls of mankind. No place on earth needs the correcting hand of the creator more than we ourselves.

Some within the Great Tradition have posited that the anagogical is “where the soul ought to tend.” This spatial metaphor is useful, as the anagogical is often experienced as a kind of ecstasy: a feeling of standing outside of yourself—of unity with some larger place or people. In Matthew Arnold’s “The Buried Life,” he articulates those rare moments of clarity that come like “A bolt is shot back somewhere in our breast, / . . . A man becomes aware of his life’s flow, / . . . The hills where his life rose, / And the sea where it goes.”

The imagery of nature speaks to the “world” that each of us is and contains. Because each of us contains this inner cosmos, together we share “soul” and we generalize by speaking in terms of mankind’s “soul.” Each of us can become a new creation, “behold if any man be in Christ . . . all things have become new” (2 Cor 5:17, KJV).

Handel masterfully presents and illuminates a beloved sequence of Scriptures, which many of us cannot hear or read without his music coming to mind. They unify the Christian hope of salvation with Old Testament prophesy. His powerful settings boost our enthusiasm for and connection to the great drama of salvation, drawing and helping us to be comforted, to anticipate and to wholeheartedly rejoice! Part I of the Messiah inspires the soul with a vision of justice, and new creation. Participation in the reverence, awe, and nobility of this music is a transformative experience, worth engaging in this and every Advent season.

Join us in the next and last article of our series as we consider the beautiful layers of meaning present in the Marian hymn “Es ist ein Ros’ entsprungen” (“Lo, How a Rose E’re Blooming”).

Jonathan and Laura Councell

Jonathan and Laura Councell are classical educators in Beaufort, South Carolina. Jonathan is a graduate of the CiRCE Apprenticeship, serves as chair of the humanities at Holy Trinity Classical Christian School, consults, trains teachers, and writes curriculum. Laura earned her Doctor of Musical Arts degree from UNC Greensboro. She has a private voice studio, teaches music at USC Beaufort, and tutors in Romance languages. During the summer, Jonathan and Laura run the Classical Arts in France program. In the fall, they host an epic Hobbit party.