Putting Poetry Back in Brains

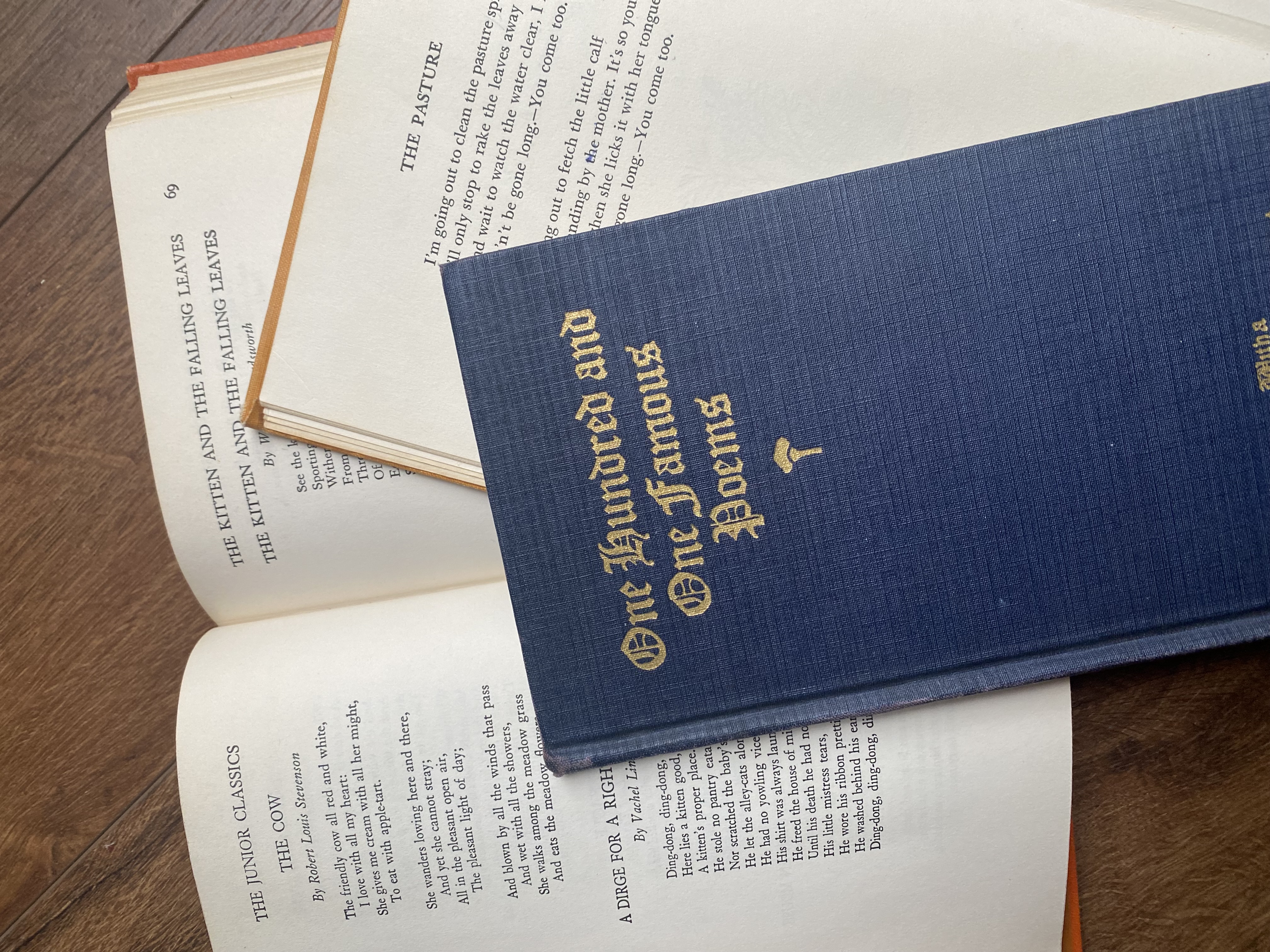

I had the great fortune to be classically educated by my parents. It involved, of course, a great deal of language and literature and a more than bountiful serving of poetry. I encountered “Hiawatha” and “Ring, Wild Bells,” “The Ruin” and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Shakespeare, Donne, Browning, Dickinson, Rossetti, Dante, and Frost were frequent companions of mine throughout school. Nor was I only exposed to great poetry: I was also required to memorize sections of the greatest poems, from the first canto of the Inferno (which I can no longer recite), to the entirety of “Horatius at the Bridge” by Macaulay (which I can still partially recite), and the prologue to “Evangeline” by Longfellow, my namesake poem (which I can still entirely recite). And while I may not recall all my childhood poems any longer, I have carried with me the momentum of memorization into my university career, where I have discovered that fewer and fewer people love and learn poetry anymore.

Peers in my English classes do not read Milton and Donne, let alone Marlowe, Michelangelo, and Pushkin. Ginsberg does not ring a bell with them—indeed, not even our own emeritus professor, Fred Chappell. This is not their fault: they were not taught to enjoy poetry, nor shown how to memorize it. Poetry can be difficult to grasp and needs good instruction to probe its riches. Meters, structures, and syntax are not as straightforward in poetry as in novels, and without guidance, a student will struggle to appreciate the beauty and magnificence of a poem. But its difficulty should not convince us to cast it aside! The very opposite: like a good cache of pirate treasure, poetry requires some digging, some effort to reach. It is worth the reading and struggling to grasp, because it expresses the deepest truths of humanity in the most beautiful language. As Keats writes in “ Ode on a Grecian Urn,” “Beauty is truth, truth beauty…” Both of those are present in poetry more fully than anywhere else.

The first order of business, then, ought to be the inculcation of our students with the greatest of the poetical tradition. As scholars like Anthony Esolen have pointed out in various interviews, poetry is the universal literary form, shared by every culture and tradition. It is a disservice to the next generation not to give them the gifts of the poets. Countless great poems from across the world have been forgotten by our students and children; great treasures have been lost and must be regained. Every young boy should know “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” and every young girl will love “Annabel Lee.” The Western tradition is rich in poets to read, but so are the Eastern European, Asian, and Middle Eastern traditions. A particularly rich diet in poetry for a student would include Michelangelo, Rumi, and Pushkin. Because poetry is the only common form of literature to all cultures, it is the only form of a literature that can easily transcend borders of culture and time to be shared with everyone.

But it is not enough simply to introduce good poetry to our students. We must also make them memorize it. What good is being aware of Milton and having read Paradise Lost, or having glanced over Spenser’s Amoretti sequence, if you cannot recognize it when it is quoted in a novel or reference by another poet? How much richness of John Donne’s “The Bait” is lost without knowing of “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love,” and Raleigh’s response “The Nymph’s Reply”? The opening sections of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse loses some of its potency when one cannot recognize Hardy’s poems in it. Children are incredible at memorization and they enjoy the challenge. Start with short poems with younger children, to instill in them a love of the words and an ease of memory that will serve them well in later years. They easily memorize songs and nursery rhymes; add to this, poems by Robert Frost or the Psalms. As they get older, look to longer poems. Consider such selections as the beginning of The Iliad, or excerpts from The Faerie Queene. As they grow older, they will also naturally gravitate to specific poets and will be more keen to memorize their poems if they have been given the tools to do so. My grandfather learned the entirety of “Tam O’Shanter” by Robert Burns in his old age! As a Anglo-Saxon specialist in literature, I lean towards such poems as “The Seafarer” and “The Wanderer” to memorize, but I frequently read poetry from all centuries and have a long list of ones I wish to commit to memory—everything from “The Anniversary” by John Donne to “The Journey of the Magi” by T.S. Eliot.

We hope, and expect, our children to know the basics of Biblical history and story. We buy books, read stories, and ensure that David and Goliath, Zechariah, John the Baptist, and the good Samaritan are characters they are familiar with. We wouldn’t dare raise children without introducing them to the Holy Bible. And we would be foolish to raise children without introducing them to the richness of our civilisation’s poetry. Nor do we simply expect our children to be passingly familiar with the Bible; we want them to memorize verses and to be deeply rooted in the Scripture. The same principle ought to apply in our instruction of poetry. After all, isn’t most of Scripture poetical in structure? God speaks in poetry—and the great poetry of this world brings us closer to God.

Read poetry, share poetry, memorize poetry. Impart it to your children—impart it to your neighbours and your friends. Poetry was meant to be recited, loved, and given as a gift to others.

A Very Short List of Poets to Begin With:

for children: Robert Frost, the Mother Goose nursery rhymes, the Psalms, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Thomas Macaulay, Robert Louis Stevenson, Ruyard Kipling, Henry Longfellow

for teenagers: Michelangelo, Allan Ginsberg, Emily Dickinson, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, Dante Aligheri, Anthony Hopkins, Aleksandr Pushkin

for adults: John Donne, George Herbert, Christina Rossetti, John Milton, Robert Burns, Caedmon, Rumi, Ben Johnson, Thomas Hardy

Evangeline Lothian

Evangeline Lothian is a student currently pursuing degrees in both English Literature and Classical Studies. Her interests lie with Anglo-Saxon and medieval literature, as well as J.R.R. Tolkien, epic poetry, and the influence of Catholic theology on literature. When not writing term papers and research articles for different publications, she can be found writing her own novels, knitting another pair of socks, or working through a Russian textbook.

1 thought on “Putting Poetry Back in Brains”

Evangeline,

Hello Evangeline, Grampa Joe here.

In you ‘blog’ you suggest that I could quote Tm O’Shanter with a Scottish brogue. I must confess that this was not me it was MY Grandfather. He was Scottish and he could quote Tam O’Shanter with a full and barely understandable Scottish brogue. I remember it very well. I do remember some poetry as has been my way since I learned to read. One poem is Horatio at the Bridge: “To every man upon this earth death cometh soon or late. How can man die better? By facing fearful odds. In the footsteps of his fathers and the temples of his Gods.” I cannot recall the whole poem and I do not Google to find out…. it is from whatever sits in my memory so perhaps a word or two might be different. That is my way.

Your article and the poets and poems you recommend are wonderful.

As you are too.

Grampa Joe