Order and Sight: An Encomium for the CiRCE Apprenticeship

This article was originally published on the author’s Substack platform, Polytropism, and is published here with permission.

I did Classical education backwards.

Classical educators love talking about the trivium, the three stages of grammar, logic, and rhetoric that constitute the broad developmental categories from kindergarten to twelfth grade. Together, they function like a rhetorical epicheirema, a hierarchy in which each successive stage perfectly prepares the student for the stage that comes after it. And I did it backwards.

To be clear, this is no one’s fault, and it’s a good thing I found classical education at any stage, let alone grammar. My parents enrolled me in a classical school in 8th grade, a sort of last-ditch effort to put me in any place where I might apply myself and learn something. I arrived just in time for the logic stage and saw it through the rhetoric stage. Following a brief diversion into the world of secular liberal arts, I was immediately hired out of college to teach grammar classes in a classical school, which I did for ten years.

So, I went from a brash logic and rhetoric student to a resigned grammar teacher. I’ll try to be delicate about this, because I wouldn’t change a thing, but those were difficult years. I had a job because I knew Latin and shared the customs and worldview of classical ed (I often like to say I was hired for my high-school diploma rather than my college one), but truthfully, I was adrift in many of the ways young, unmarried men are adrift. I made no money. I had little ambition. I put no stock in the future. But the school was there, and I stayed with it, submitted to its form, because deep down I knew it was one of the only things I had in life that I would not have to give an account for at the seat of judgement. It was “kingdom work,” as the Protestants like to say, and I clung to it as such.

Eventually, however, something was going to have to give. After ten years, I needed a vocation, not just a job. I had a decent side hustle as a freelance writer, writing articles and reviews about videogames for various websites, and my foray into stand-up comedy was promising. My album was well-received, and I was able to go on my first tour the summer after. But I knew that I didn’t have what it takes to be a road comic, and I had neither the money nor the desire to try to go to New York or Atlanta to break into the writing scene. I had roots in classical ed, and of the options I had at that point, only that was nourishing my soul. Enter the CiRCE Institute.

Actually, I must be honest, the CiRCE Institute had entered long before that. My mom had undergone the apprenticeship some years earlier and had encouraged me relentlessly to apply for it. I put her off, both because of my uncertainty and my guilt over how prodigal I’d been with my college money. In the Spring of 2021, though, things were looking up for our school. Covid had strapped a bit of a rocket to our backs, fueled by parents fed up with quarantine and “distance learning” (spit upon it), and I was promoted to an admin role with a generous raise. It was a prime opportunity to pursue a deeper understanding of classical education, and the CiRCE apprenticeship is purpose-made for that task.

I don’t want this to be a breakdown of everything you do in the apprenticeship. They have a website for that. Nor do I want this to be a strict recollection of my time there. It would be long and exhaustive and ultimately wouldn’t mean very much to you. Nor do I want to say that it changed my life, because that’s a cliche, and also, while it is true enough, it’s not the exact truth.

Instead, the CiRCE apprenticeship gave me two things: order and sight. It exposed the structure and place of all things in classical education and gave me the language and understanding to know it and share it. If you have been reading any of my recent work since January, you are basically reading out of the notes I have taken at the apprenticeship retreats. The CiRCE apprenticeship is full of practical training and teaching insights, how to teach mimetically and Socratically, etc., but its supreme value is that it spoke to me on the level I really needed: by telling me all the things I knew to be true but didn’t know how to express.

Regarding order: the apprenticeship made me aware that education has no true starting point other than the soul. It also made me aware that while the trivium is a broadly effective framework for the school, the truth is much deeper than that. There is an order of knowing and learning in the classical tradition that begins in the home, before a student ever sets foot in a classroom, with music and gymnastics, and ends, or rather, finds its fulfillment, decades later in the dining room of a Jack’s, talking politics and theology with your fellow semi-retirees over biscuits and coffee (that reference may be a little too local for some of you, but trust me, it works).

Regarding sight: the apprenticeship made me aware that human life is normative. There are a lot of different ways to define what normative means, and I have witnessed more than a few fierce debates on the subject, but when I use the word, I use it as shorthand for the fact that life is a union of spirit and material, in which each side influences the other, and that influence pervades its community, shaping its norms. We read Scripture and the great books and the ancient philosophers because they prompt us to ask questions and craft answers to those questions regarding what we encounter and how it affects us along the two dimensions of life. Having “sight” for an encounter means understanding what a thing is both materially and spiritually, and how to treat it properly, with propriety.

In other words, the apprenticeship gave me the means to perceive the Logos, which is the chief end of education. Properly applied, this is not something that has to be taught explicitly, it can be received poetically through education, but our modern culture and concepts of learning are so scattershot and ignorant of these things that they necessitate the apprenticeship’s doing so. And further, education is a river. It flows for the duration of our lives, and as such, the mark of a good education is that it imparts the concerns of asking normative questions and treating things with propriety so that a person desires to do those things for their own sake. The CiRCE apprenticeship is about helping people order themselves and then getting them into the stream. I cannot yet perceive the Logos in everything, nor will that work ever be finished, but I’m in the stream now, and it happens more and more every day. Heck, my entire encounter with the eclipse from earlier this year is exactly what I’m talking about:

The eclipse is a gift, a brief window into which we’re permitted to see the unseeable as if it were any other object. This is a privilege the sun will never know, because while it’s a creation of God, and perhaps His most powerful creation, it’s not one of His children. I felt humbled, sure, but I did not feel small. I did not feel insignificant, or alone, or helpless, or any of the other putatively humble nihilisms that our pop-science overlords like Tyson and Nye direct us to express when confronted by the Almighty.

Instead, I felt like a child, an inheritor. I felt like I was being allowed to, and I return to this word intentionally, countenance a thing I could not safely reach for myself, like when I take a bauble off a shelf so my daughter can inspect it.

My reaction to that encounter was only possible because of the apprenticeship.

To say that I have enjoyed my time in the apprenticeship is a galactic understatement. When I joined, I was disordered and getting by, sustained pretty much exclusively by the Eucharist. My mind had dulled in my work, and it was time for a change. I read little and watched too much. I didn’t think about anything past an analytical level. I drank without company or occasion. I was still living that semi-feral bachelor life, in a shoebox apartment filled with dusty Bibles. In six months, nearly all of that changed. I started dating my wife, attended my first retreat, and got engaged. Now, on the cusp of graduation, we have a home and a burgeoning family life. I wouldn’t go so far as to say, “The apprenticeship made me a man,” but it certainly attended to my becoming a man. It enriched, and, in its way, blessed the assumption of real responsibilities that I had desired for many years by tying that assumption to learning the things I needed to know in order to transform my job into my vocation.

That is what the apprenticeship can offer you. Order, sight, and a place in the stream. It is not, principally, a place to learn how to be a classical teacher. Instead, it is a place to learn how to be a human, an ordered union of spirit and material, animated by God, who can encounter other humans and treat them with the propriety they deserve, by teaching them. That is, leading them to Truth. Helping them perceive the Logos. I will close with one more example.

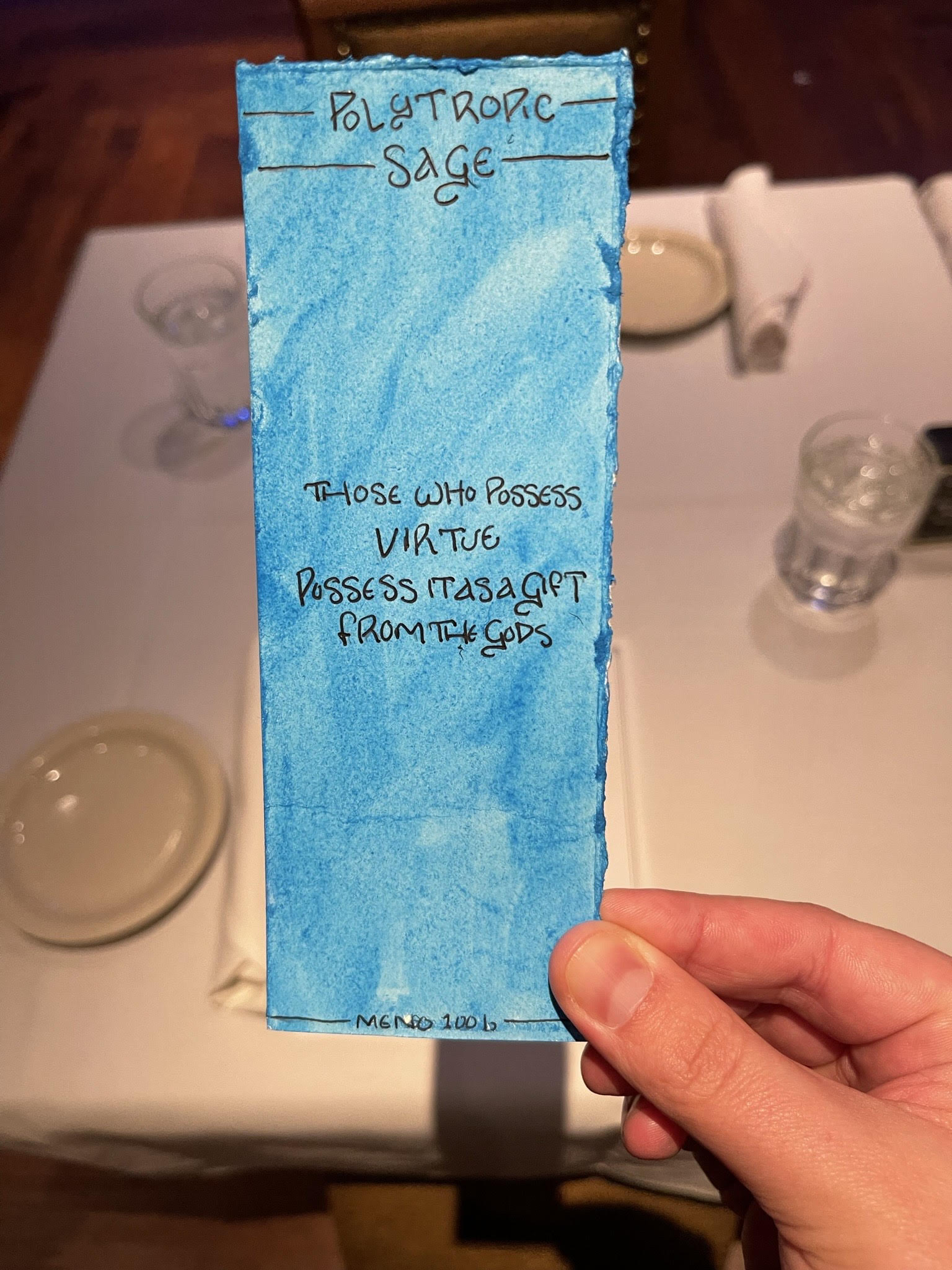

One of the traditions of the apprenticeship, at least in my group, is that each apprentice is given a “poetic name,” a name that reflects a truth about their character or personality, and an aspect of themselves that they should aspire to. The name given to me at the end of my first retreat was “Polytropic Sage.” Obviously, Sage is the aspirational half of the name. I’m not a sage and I’m never going to proclaim myself one. But Polytropic? I didn’t know what it meant at the time, but the second my head mentor explained it to me, I felt a sense of genuine recognition and understanding of who I was, like I had been seen for the first time.

Polytropic comes from the Greek poly and tropos, “many” and “turns.” It’s one of Odysseus’s nicknames in The Odyssey, sometimes translated as “many ways” or even “many manys.” Polytropism, for me, means turning every encounter I have over and over in my mind before deciding what its propriety is. This is distinct from, say, overthinking, because eventually a dogma is found, right and wrong are identified, and I rest in my certainty. Like the Ents, I’m not likely to give you an answer to something on the spot, but eventually, I always stumble across Saruman’s border with Fangorn, and see things for what they are.

My poetic name is a logos that I’ve been able to use both as an aid and a challenge to grow. I have a closer relationship with how I think now, and it’s easier for me to know when to be assertive and when to trust a mystery whose answers haven’t yet flowed to me in the stream. That’s the level at which the apprenticeship works. Yes, I am a better teacher now because I know the mimetic sequence and the technical process of a Socratic dialogue, but I’m also a better teacher now because I know myself better than I did three years ago. I wouldn’t have that without the apprenticeship, without my head mentor, Jolly Wisdom, or my fellow apprentices.

What I have been given here is a second grammar stage of sorts, an ordered one, that I can now carry forward into the logic and rhetoric stages of my own studies and my own teaching career. If you’re a homeschool teacher, or a teacher at a classical or Christian school who wants to understand the educational norms that we are trying to renew, then there is no better pursuit than the CiRCE apprenticeship. I’ve spoken with a handful of readers who are on the fence, and my answer is an emphatic exhortation to each of them and anyone else reading who is considering the apprenticeship: Go.

To my head mentor, and to each apprentice, past and present, who has shared these last three years with me, please know that they have been the best of my life because of your warmth, and wisdom, and sincerity. Gaumarjos!

Adam Condra

Adam Condra is the Dean of Agape at Omnia Classical School in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. He writes about classical education and pop-culture at Polytropism on Substack and runs his mouth at PolytropicSage on Twitter.