The Offense of Hierarchy

The word hierarchy has become offensive to our modern ears. American society has dethroned kings, popes, aristocrats and now takes aim at billionaires. Our culture loves the egalitarian turn — the general who dines with the common soldiers and fights on the frontlines; the girl who can shotgun beers, curse like a sailor, and fight just like “one of the guys;” the torn-down statue because “he was no better than us.” Superior is a four-syllable curse.

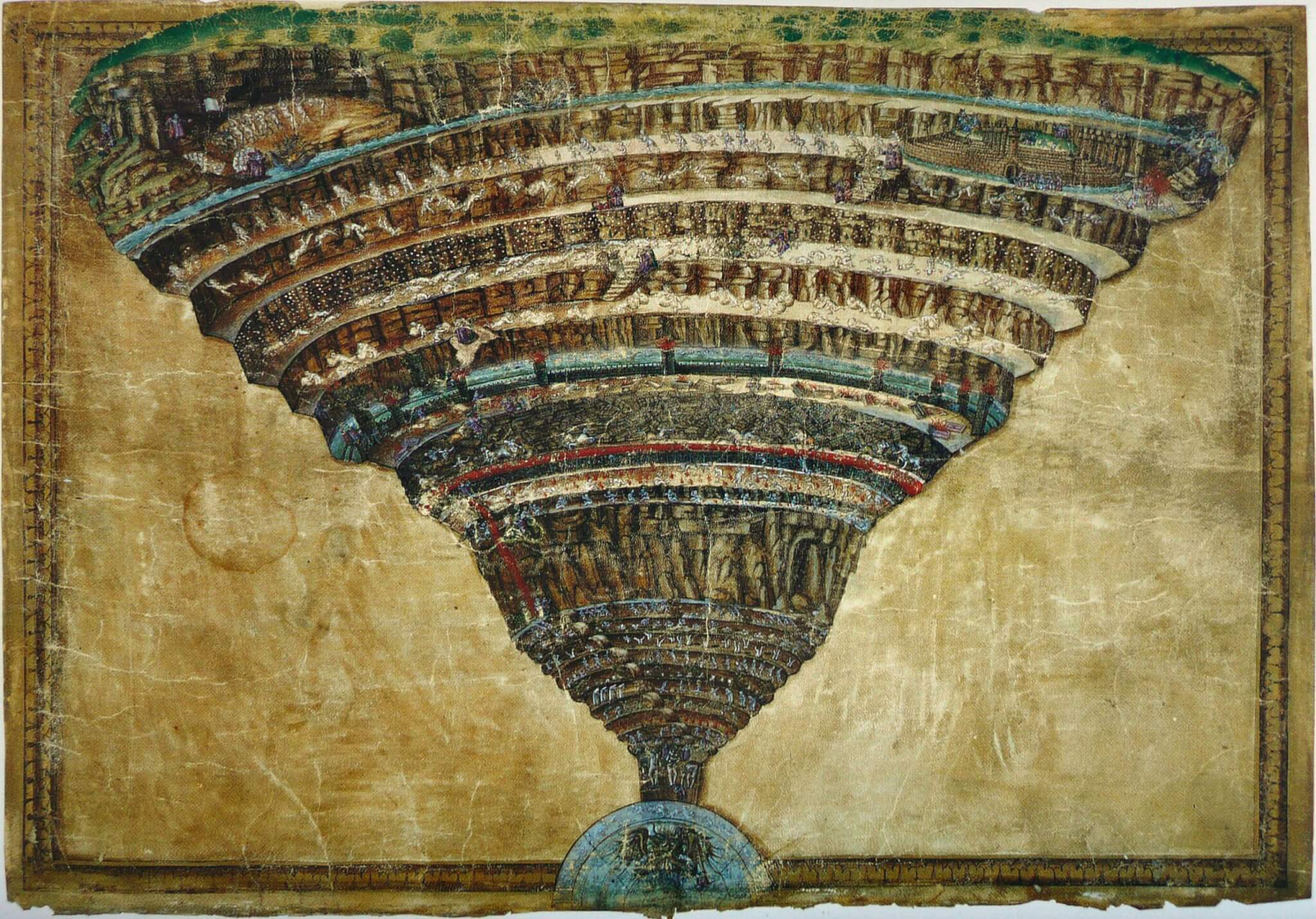

While reading through Dante’s Inferno, I was struck by the pervading hierarchy of his cosmos. Everything has its place, and everything is in its place. He merely has to note a sinner, sin, and punishment to mark their place in the universe with the precision of a point. Dante’s journey is not merely longitudinal but vertical. He descends and ascends. Even in paradise, the hierarchy persists. As Peter Kreeft once noted, many think the medievals believed the world was flat. Instead, it is moderns who believe in a flat universe, for Dante’s is oppressively altitudinous as he moves from the lowest point in the universe to the highest.

Dante’s Hell is arranged according to the Ethics of Aristotle. There are two kinds of vice: incontinence and malice. Incontinence stems from the weakness of reason and the will. It occurs when the desire for some good thing overwhelms the rational and incites man to sin. Malice arises from an evil will that desires to injure others; this violence may be perpetrated through force or fraud. Since fraud utilizes man’s unique capacity of reason, it is the more serious offense against God. Animals can maul, but they can’t cheat at poker. As Dante descends through Hell, he illustrates the descent of the soul through vice. There are worse sins than others.

The ordered nature of vice and virtue is an offensive suggestion to our modern ears. After all, every sin is equal in the sight of God. Hell is the just punishment for every sin, no matter how small, so there is little sense of speaking of weighty or minor sins; they are all serious. Likewise, anyone who calls upon the name of the Lord is equally saved, so there is no basis for calling one more righteous than another.

When it comes to sin and righteousness, we are relativists. Because we have no concept of hierarchy, we cannot talk sensibly about virtue or vice. Is calling someone an idiot really as evil as massacring a village? Is lying to your spouse as vicious as committing adultery? No one actually believes that the millionaire donating $100,000 has behaved more righteously than the middle-class person who sold all his goods to give to the poor. We want to claim that no sin is worse than another or that no person is more righteous than another, but we contradict ourselves in our judgments.

Our Lord proclaimed that “it will be more bearable on the day of judgment for the land of Sodom and Gomorrah than for that town” (Matt 10:15). Evidently, Jesus believed in more serious punishment for weightier sins. He also distinguishes “weightier matters of the law” from minor aspects (Matt 23:23). Paul identifies sins which are not even practiced among the pagans and which require excommunication from Christian fellowship (1 Cor 5). While we may object to some sins being more serious than others, no one lives as if they were all equal. We do not prescribe life sentences for going 5 miles over the speed limit. Murderers are not released after paying a $500 fine. Our law recognizes motive and consequence when sentencing.

Embracing a hierarchy of vice is difficult for us because we cannot trust our own judgment to order sins properly. We tend to either view our own sins as insignificant while magnifying the sins of others, or we fixate on the sins for which we have the most shame while overlooking our other sins. In either case, we are led by our own emotions and how we feel about sins rather than a rational order. Students are likely to feel more shame over pornography than cheating on a test, even though Dante places fraud in a far lower circle than lust. We are likely to excuse our calculated betrayal of a friend while condemning their angry outburst in response. Our ordering of vice is actually disordered.

Engaging with Dante’s Commedia allows us to look at our lives from a fresh angle. His hierarchy causes us to question our own priorities and judgments. Thinking about degrees of wickedness allows us to prioritize and strategize for fighting against the regime of sin and death. There are many evils in our world and in ourselves, yet some have more dire consequences. Dante gives us the categories to think about sins. The Commedia is a compendium of vice (and virtue).

Further, Dante’s ordering of wickedness may shine a light on the hidden areas of our lives which we do not consider especially wicked. When we think of the word sin, there are likely a handful of specific sins that immediately come to mind. Perhaps it is lust, the love of money, or gossip. Yet we often overlook the more hidden and, in Dante’s world, serious sins that make up the atmosphere in which we breathe. We are unaware of the extent to which pride infiltrates our every decision or the calmly malicious manner in which we seek our desires.

The cosmos is ordered and unified. Just as there are degrees of judgment in Hell, there are degrees of reward in Heaven. Perhaps Dante’s imagination helps us unify the one and the many. The redeemed in Heaven are all in the light of God’s presence and enjoy His favor, yet vary in the degree of their happiness according to how they are able to receive His bliss. All the sinners in Hell are cut off from God’s grace and have no hope of deliverance, yet experience different degrees of torment according to their wickedness. Dante’s imagination helps us to embrace the hierarchy of the world and find beatitude in God.

Austin Hoffman

Austin Hoffman has written articles for Front Porch Republic, The Imaginative Conservative, and Classis. He loves his wife and three boys dearly.