How to Teach as if Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Were Your Students

The teacher’s hope for his students is that they will repent. We aim not to inspire, empower, train, ignite, or prepare anyone for the real world. Instead, we pray that our students will see the truth about themselves, their shallowness, ignorance, selfishness, or laziness, and that in seeing this truth, they will be set free.

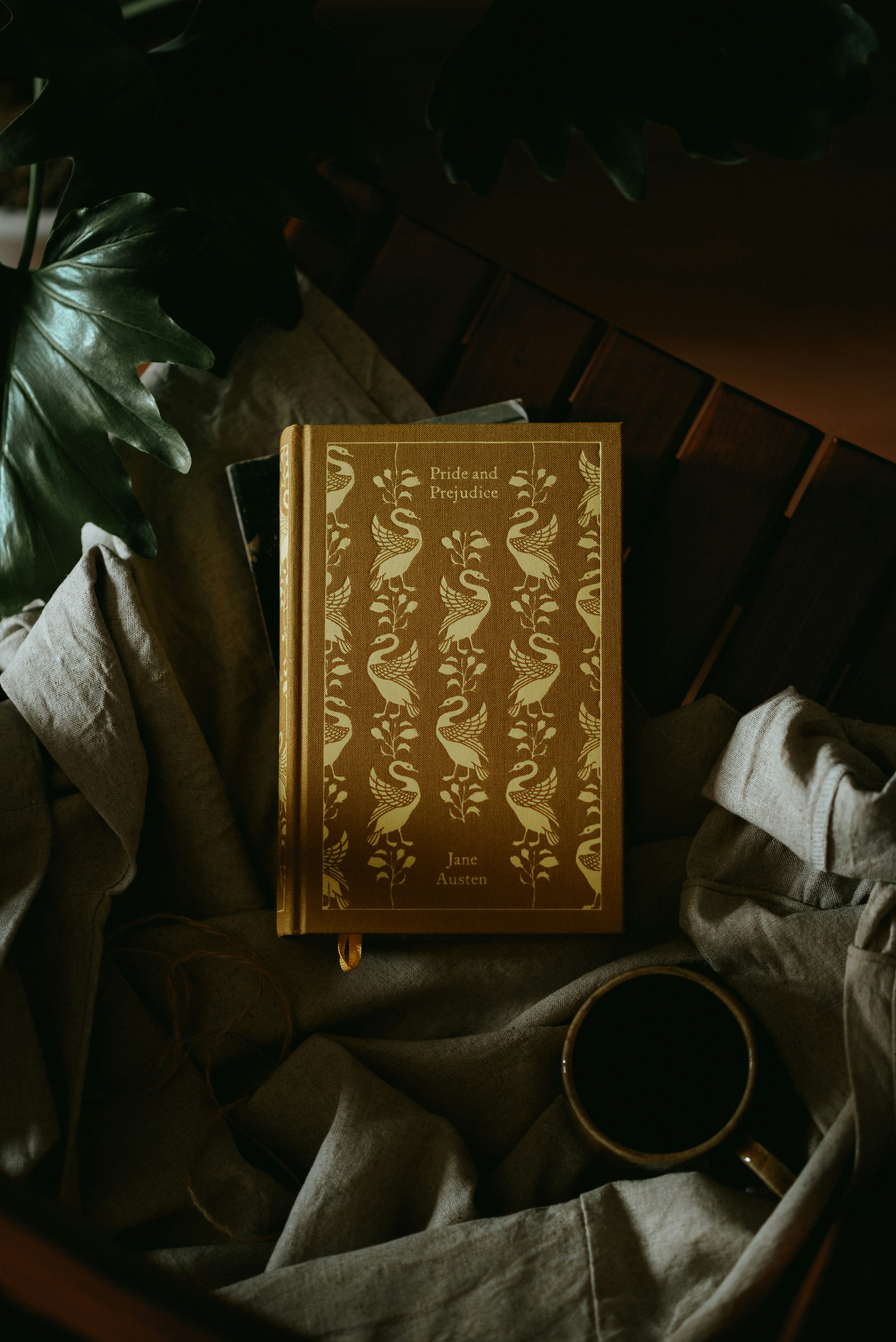

If repentance is our goal, then we should be experts on how teenagers change, and for that, Jane Austen gives us a master class in her novel Pride and Prejudice. Amid the dances and obsessions with money, there are two young people who bring about repentance in each other, setting both their lives on a new trajectory.

Our first penitent is the story’s heroine, Elizabeth. Joshua Gibbs believes that Elizabeth’s repentance is believable only if we accept that her earlier behavior is truly awful. He sees her on the path to becoming her embarrassing mother, Mrs. Bennet, but I argue the opposite to be true. Elizabeth is an understated virtuous heroine who changes and becomes more virtuous because she is already good. And from that premise, I suggest that the students most likely to change are the ones who are already on the road to virtue.

Austen judges her characters by the classical virtues, and Elizabeth embodies charity, justice, and fortitude. First, Elizabeth is kind. Though an overused and sentimentalized word today, Elizabeth does not just talk, she acts with kindness. When her sister Jane is sick and abandoned at Netherfield, Elizabeth hikes over to comfort and stay with her, ignoring humiliating jeering by Mr. Bingley’s sisters. This act does not go unnoticed. When Elizabeth attempts to figure out what made Mr. Darcy fall in love with her when there was “no good” in her, he counters with her visit to Netherfield: “Was there no good in your affectionate behavior to Jane?” Elizabeth does love her sister, and, later, when Jane’s love interest, Mr. Bingley, ghosts her, Elizabeth watches her sister carefully, looking for signs of grief and depression.

When Charlotte is condemned to live in matrimony with Mr. Collins, to whom does she turn for companionship? Charlotte knows that Elizabeth will not berate her for marrying Mr. Collins and will bring only cheerfulness to her situation. Elizabeth does not disappoint, and by the end of her long visit, even Lady Catherine De Bourgh is loath to see her go.

Elizabeth’s friendliness is more than an extroverted Myers-Briggs personality trait. She loves other people, which is why she cannot stand Mr. Darcy and his “selfish disdain of the feelings of others.” He is delusional if he thinks she is going to marry the person who ruined the happiness of a beloved sister. She is not completely wrong about Mr. Darcy because he later admits to being selfish, but that does not keep him from admiring Elizabeth’s loving nature. In fact, Mr. Darcy, like Elizabeth, loves his own sister. In Elizabeth, he sees a woman who will love him and love Georgiana.

Mrs. Bennet, on the other hand, does not love anyone but herself. Her enthusiastic approval of Mr. Collins’ proposal and her weird exuberance over Lydia’s marriage to a lowlife prove that she cares only about her own comfort and status.

Second, Elizabeth’s kindness is not sentimental because she balances it with justice. Yes, she was gullible and swallowed Mr. Wickam’s tale of woe too quickly, but she was genuinely angry about the injustice of it all. Though Mr. Darcy blows off Elizabeth’s other criticisms, he goes to great lengths to justify himself in his dealings with Mr. Wickam. For all his faults, Mr. Darcy is not unjust, and he respects Elizabeth’s sense of justice by making sure her charges against him are satisfied.

Lastly, Elizabeth shows fortitude. We think of fortitude as courage in a dangerous situation, but the classical idea is more like sustained strength and patience, and Austen transposes this virtue beautifully into a woman’s world. Elizabeth does not face hand-to-hand combat or monsters at sea, but as a poor gentleman’s daughter in Regency England, she must fight for her virtue by turning down solvent offers of marriage and withstanding the consequent verbal abuse. We can almost hear the devil’s voice through Mr. Collins: “It is by no means certain that another offer of marriage may ever be made you.”

We cheer for Elizabeth when he turns down Mr. Collins, but when she turns down Mr. Darcy, we wonder if she has eaten something bad at Rosings. It is difficult for us, especially the men, to imagine the temptation she faced. Mr. Darcy is fabulously rich, which is always important, but especially when you cannot get a job and might at any moment be turned out of your own home. He is respectable with good connections, so this marriage will give you the highest status in society. And let us not forget that Mr. Darcy is handsome! Could not rich, respectable, and handsome make up for a less-than-ideal proposal?

Elizabeth does not even consider it. After trying to be polite, she lets him know that he is the last man in the world she would ever marry. At this point, Elizabeth is hardly human. I can imagine our brave soldiers storming the beaches at Normandy. I can imagine Louis Zamperini surviving the ocean and prison camp, but I have never met a woman on this earth who would have turned down Mr. Darcy. Girls compromise for security and status all the time. The equivalent would be turning down the actual Colin Firth if he were a baptized Christian. Only our courageous Elizabeth had the fortitude to say “no” to someone she perceived as proud and unkind, and it was this act of courage that woke up the conscience of Mr. Darcy.

After reading Mr. Darcy’s letter, Elizabeth does not blame Mr. Wickam for the misunderstanding. She realizes it was her vanity that caused her gullibility, and she repents. But even after Elizabeth admits, “Till this moment I never knew myself,” she does not regret her decision to refuse Mr. Darcy. He has been cleared of gross negligence, but he is still proud and unfeeling, and if he wants to marry a worthy woman, he will have to change, too.

Mr. Darcy’s repentance is much more painful. Though it happens in the background (Austen prefers to show action from the female’s point of view), Mr. Darcy tells Elizabeth he agonized for weeks over her words. Unlike Mr. Collins, he turned his bitterness to a “proper direction” and sees that even if she had been wrong about some facts, Elizabeth had pegged him right when she said he had not “behaved in a gentleman like manner.” Those words stung, but like Elizabeth, Mr. Darcy wanted to do the right thing, and when his faults were made known to him, he owned up to them. He does not just say, “I’m sorry.” Mr. Darcy acts to prove that he is a new man. Elizabeth is not won over by Mr. Darcy’s big house; her heart melts (as does ours) when he is all politeness to her aunt and invites her tradesman uncle to go fishing.

Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth are the only characters in the story that change, and the circumstances that cause them to change prove that they were already seeking to be good. Other characters, under more dramatic circumstances, do not repent. Mr. Collins gets a surprising refusal from Elizabeth, and instead of self-reflection, digs in his heels and commences to scorn Elizabeth at every opportunity. Lydia’s shotgun wedding brings no self-awareness to her or her mother. Mr. Bennet does experience some bad feelings about his role in the family debacle, but he assures Elizabeth that they will quickly pass. Austen knows what we all know—that people with bad character find it hard to change, and if they do, it usually takes a catastrophe. Tolstoy will give you a fatal disease, and Flannery O’Conner will put a gun to your head, but for Elizabeth, all it takes is a polite letter, and for Mr. Darcy, the suggestion that he had not behaved “in a gentleman like manner.”

When discipling students, we tend to play Whac-A-Mole. A student’s grades plummet, her demerits skyrocket, and we call her in for a meeting. We ask what is going on in her heart, give her some advice, and then put her at the top of our prayer list. But Pride and Prejudice offers some counter-intuitive advice. Instead of concentrating on our problem students, we should focus on the students with souls ready for change.

How many of our best students leave us without one-on-one discipleship because they never caused us any trouble? The ones who keep the rules, get good grades, and pay attention in class are the ones who are most open to our admonishment, yet we spend our time rebuking fools instead of correcting the wise. Even our best students are hopelessly naïve, anxious, and full of themselves; they need our guidance to develop budding virtue. Every school will have its Lydias and George Wickams, and we will continue to love them, admonish them, and pray the best for them. We believe in miracles. But instead of constantly playing Whac-A-Mole, Austen wants us to spend more time with our young Elizabeths and Fitzwilliams.

Dana Gage

Dana Gage is a mom and pastor’s wife in Brooklyn NY. She teaches Great Books and Rhetoric at Trinity Christian School.