Hovering Over the Waters

“For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—”

— Ephesians 2:8

“Here is the path to the higher life: down, lower down! Just as water always seeks and fills the lowest place, so the moment God finds men abased and empty, His glory and power flow in to exalt and to bless!”

— Andrew Murray

The Greco-Roman world envisioned the abundant aspect of grace as Thalia, a supernatural being commonly pictured frolicking naked with her two sisters. Together they were the Three Graces (Charites), the sensuous triad of the ancients. Whether in voluptuous embrace or cavorting in a garden, they were frequently depicted in an unbroken circle, their relationship signifying a continual act of giving and receiving the benefits of goodwill towards others. For the ancients, grace was the love that united a community, offering and gratitude underwritten by free choice and moral obligation and visualized as eternally young, beautiful bodies.

When I gaze on an image of Thalia and her sisters in pastoral surroundings, I’m reminded that the embodiment of grace extends to the natural world. Though in its essence grace is formless, I sense that it pools like thick honey in the suchness of tangible things. Grace is the divine outflowing of relational energy of interdependence amongst all sentient beings. But we often experience it as a momentary eruption (as gracefulness) in the created order.

Grace has the character of an intimate flow that wells up gently, filling our broken places and bringing us closer to God. But paradoxically, it’s also boundless and awesome, filled with the unending riches of mercy that Paul describes in Ephesians 2:5: “alive with Christ even when we were dead in transgressions—it is by grace you have been saved.” In their effortless lilting rhythm, dancing nymphs adequately capture the aspect of grace as the delicate tenderness in God’s love and the relational energy of interdependence amidst creation. But how to visualize the abundant aspect of grace?

It was in the Romantic era of the nineteenth century—the golden age of landscape painting, that the aesthetic categories of the Pastoral, the Picturesque, and the Sublime were established as ways of conceptualizing human relationship to the natural world. Pastoral landscapes celebrated human dominion over nature, while those labeled Picturesque were made to uplift the viewer with charming scenes of unspoiled nature. By contrast, Sublime landscapes were fearsome, overwhelming, and humbling all who stood before them with a show of nature’s wild force.

When art disrupts our habits of seeing, grace can show up suddenly. The different forms of representation of grace remind me of the numerous ways we experience it in the physical world. Grace can be equally evoked in the expressive intensity of Romanticism or the cool detachment of Classicism, with its emphasis on order through balance, harmony, and proportion.

Comparing our Classical triumvirate of the Three Graces with the landscape concepts of Romanticism exemplifies how aesthetics can work like modes of grace. Every visual style can communicate something else about divine generosity, thus the sheer diversity of Western art is analogous to the varieties of grace that manifest in human experience. Classicism and Romanticism are aesthetically at odds, each communicating grace in a different language of beauty. But whether grace takes delicate or awesome form, art makes it visible by presenting a natural world infused with wonder.

By now, our experience of nature has been fully conditioned by images. The cell phone’s intrusion on our outdoor excursions is commonplace. It’s the primary instrument we use to self-mediate our relationship to the environment. Nature becomes a landscape when we capture it in a frame, but the act distances us from the place. Since the inception of photography, artists have grappled with questions about how images shape our relationship to nature. When we look at a tree, do we see its treeness or our idea of a tree, conditioned by ordinary images? To really see the tree in its essence requires that we be receptive to it in a state of contemplative awareness as we stand in nature. A work of art can invite deep reflection on a familiar place, like the ocean. They can inspire us to go back and look at nature again with new eyes. Art has the capacity to invite the deeper dimensions of the mind and heart, bringing us back to primary experience. When its subject is the natural world, we’re reminded of our interdependence with the created order and invited to experience its presence the next time we’re outdoors.

Drawn Into the Sea

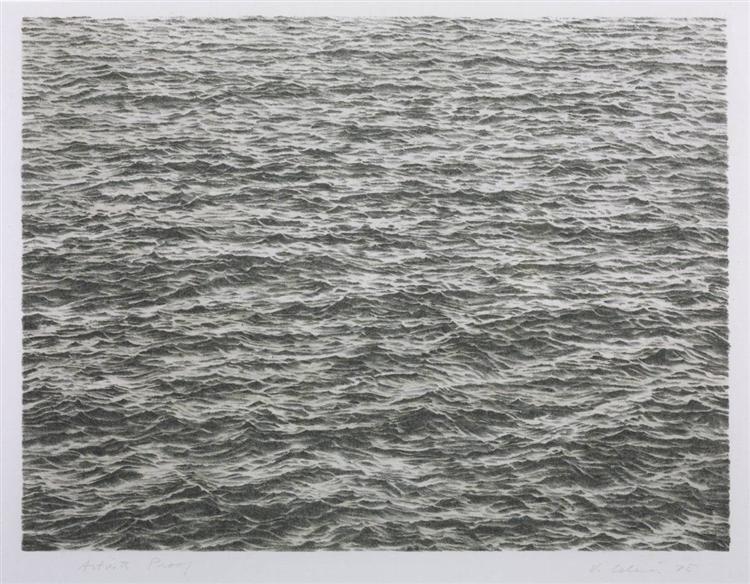

In the late sixties, Vija Celmins began drawing the sea. From a pier near her studio in Venice, California, she took photographs of the Pacific Ocean, a boundless expanse of waves filling her camera lens. Previously Celmins had been using photographs she found in magazines and books, as well as snapshots she took of common objects in her studio, as a basis for her drawings and paintings. She eventually began applying her photorealistic approach to images of the natural world—spider webs, deserts, night skies, planets, the surface of the moon. But it’s her drawings of the ocean that stir me the most.

Pencils in hand, Celmins set about translating her photographs of the sea’s rippling surface with delicate precision. Meticulously, she would cover the paper with fine marks that would coalesce to form something both otherworldly and quotidian at once. Individual lines are lost in a rhythm of pure tonality. Despite their shocking verisimilitude, the drawings also appear like Baroque patterns, swelling in unison. Spanning the paper’s entire surface, scattering light as they rise and fall, the drawing’s waves carry us in one direction, then the next, across an endless flowing field of particularities.

The ocean in Celmins’s drawings is sublime. I’m spellbound by the rippling crests yet sense a subtle dread in the shadows from which they emerge. They are the turbulent, billowy skin of a deep mystery barely contained. Lost in the movement of these alluring surfaces, my memory hurtles me back to an experience of the Grand Canyon. There, many years ago, stepping towards the lip of that incomprehensible gorge I felt a dizzying sensation, accompanied by the impression of being forcibly drawn into its gaping mouth. Edmund Burke wrote that the sublime causes terror like this. I backed away, but still sensed that pull, as if an energy were emanating outwards from the canyon’s depths to sweep up and swallow anything within the orbit of its rim.

Yes, I’m afraid of falling from high places, but I grew up swimming in the ocean almost every summer. And even though I’ve always been wary of its power and avoid swimming out too deep, my love of the water made me reckless on a few occasions.

Years ago, I visited a local beach with a relative and despite the rugged surf, decided to take a swim. I hadn’t been out long when I got caught in a riptide. Its force overwhelmed me and no matter how hard I swam I couldn’t advance through its furious pull. Mercilessly, it dragged me farther away from our spot on the beach and deeper into its fierce, cold darkness. I was seized with panic. A lifeguard spotted me and within seconds dove into the water and tossed me a rescue buoy. He yelled at me to swim parallel to the shore as I gripped the red, rigid plastic of the tube with all I had, struggling to get free of the ocean’s grip. Finally, it released me, and I staggered out onto the beach, exhausted, shaken, and embarrassed.

When I think of grace, I imagine a flow. To swim in its current means releasing our control valve and letting it rush in to carry us. When we catch its flow and swim with it, we’re in right relation to God, its immeasurable source. It goes mostly unnoticed unless we’re silent and still. It’s beneath the surface of experience—a movement we must not struggle with lest we drown. This quiet pervasiveness is another paradox of grace. It’s in everything but usually out of sight. Celmins’s ocean drawings hint at the eternal, boundless, depthless love that characterizes grace, a current beneath fragile appearances and fleeting events.

Celmins’s Ocean series first took the form of drawings and eventually prints as well. They resemble photographs themselves, inviting close scrutiny. Examining them, we note the texture of graphite, applied through countless tiny strokes. Like grace itself, these drawings are immersed in paradox. The scenes are empty and vast, but the drawings are intimately scaled and intricately layered, inviting us to peer in. Three-dimensional space is flattened, and the drawings are devoid of horizon, shore, or any point of reference. We’re confronted with an allover surface in which no part is emphasized over another. Spatial ambiguity is dominant, though there is a subtle sense of receding space as waves become smaller and lighter towards the top of each drawing. Depth is conveyed, but the objective isn’t illusionism. Celmins is working from one flat image into another, transmuting the way photography captures a scene into the language of drawing. As it moves from instantaneous reproduction to something handmade, the image becomes a trace of the artist’s inner search. Celmins reinvents the photograph one mark at a time, in a concentrated, meditative act that joins with the ocean’s timeless quality.

Due to her choice of subject, Vija Celmins’s drawings may seem more Romantic than Classical. But though her Ocean series leans towards the sublime in its depiction of nature’s power and enormity, her approach is cool and detached. This too casts her drawings into the realm of paradox. The photograph, standing between her and the natural world, becomes the catalyst for a contemplative process of transcription. It’s the image, rather than the direct experience of the ocean, that motivates creative exploration. Her experience of nature leads to the photograph that guides an inner journey as pencil meets paper.

A Romantic artist would draw or paint the ocean according to their personal vision, swept up in the experience of being there. Viewers would be led to see something of the artist’s subjectivity in the representation.

In its reliance on the photograph and its precise simulation of nature, Celmins’s work speaks to the hyperreal condition of our society, awash in images that condition our sense of reality. But her drawings couldn’t include such intricate detail if they weren’t based on photographs. She uses the seductive quality of mechanically produced images to pull us in, but our attention is sustained by the drawing’s materiality. Its surface invites us into the depths, literally and figuratively, so we slow down and experience the movement of being itself in a scene which at first glance might seem empty. In contrast, before nature we’re often lost in the chattering of our minds, commenting on our surroundings, or attempting to capture a picture telling everyone we were there.

Celmins’s work is classical in spirit, if not in subject matter. She’s not imitating the art of antiquity, which would risk being escapist, sentimental, or moribund in our current age. Her studio model is the photograph, which she reinvents through a methodological interpretation. Just as artists of the past would commit to the discipline of copying from plaster casts based on Greco-Roman sculpture, Celmins works not from life, but representation. In her workings of the paper’s surface, something new appears. We get lost in its materiality as drawing, imagining its making.

Classical art treats its subject in an emotionally neutral way. And by engaging with nature indirectly, so the focus is on what drawing can do, Celmins produces work that’s meditative rather than expressive. Her drawings are cool, distanced, ordered. In addition to subordinating color to line, classicism is concerned with harmony, rationality, and balance. These principles are evident in the Ocean drawings as well. Upon close viewing, each reveals its organizing structure, built up through a patient application of graphite on a white ground. The high degree of control in these drawings results in a monumental stillness, despite the energy depicted.

Touch is an important part of her art, connecting the artist to her subject (both the ocean and the photograph) and bringing us into the process, imagining the drawing being made. This tactile quality may remind us of the fleshy beauty of the Three Graces, and how grace invites a multi-sensory experience of the created order. In working over a surface repeatedly, Celmins has said she imagines that her drawings and paintings have a memory,that every stroke, whether visible or buried beneath layers of graphite, is an indelible part of the picture’s life. Like the mythical mother of Thalia, Mnemosyne, memory births grace as each stroke obscures the one before even while granting them new life.

All of Celmins’s work is labor intensive. A single drawing takes weeks to produce. The timelessness of the natural world, the endless currents of the sea, fuse with personal time in the production of each piece. Returning repeatedly to the same image and exploring subtle variations, there’s a balance and moderation to her drawings that’s classical at its core. In each iteration, Celmins adjusts her approach as her pencils explore the image, searching out new possibilities. And each drawing yields something uniquely elegant.

Celmins’s consistent rigor is almost austere. She probes every nuance of her medium when drawing. She works with a wide range of pencil grades, taking into consideration the quality of each mark, avoiding the use of an eraser, and preferring to throw a drawing out if a mistake is made. Working from one corner of the paper to another by a predetermined method, she avoids issues of composition by focusing on one tiny section at a time. Her drawing hand covers adjacent areas as she builds the image up. Her methodical approach deftly arranges each drawing’s silvery world. And in its invitation to stop and be still, her work is a welcome antidote to the excessive distractions in our society of spectacle.

Whether working with found images or her own photographs, Celmins’s work is a rumination on the relationship between the mass-produced image and the handmade. The Ocean drawings seem at first glance to partake in the culture of the hyperreal, another set of seductive commodity images that play with illusion. But when studied closely, they displace our expectations. Though their subject is surfaces, as drawings they are materially dense. The beauty of these surfaces and the inspiration of nature act together to induce the same contemplative gaze we bring to sacred imagery. Looked at this way, the drawings foreground grace in their paradox of stillness and movement as well as through their inner radiance and reference to an eternal flow. Each drawing asks us to stay and find ourselves, paradoxically, swimming in its surface of delicate lines and rich, shifting tonalities.

It’s no wonder that when I look at Vija Celmins’s Ocean drawings, grace comes to mind. Water is symbolic of God’s grace and redemption, and art offers us the opportunity to see anew, as when I feel my own spaciousness mirrored by these images of the open sea. That day at the beach, caught in the riptide, I struggled when I should have stayed calm, following the breaking waves at an angle until I was back to safety. It was a lesson in trust reflecting something bigger. We recognize the interdependence of creation when we’re immersed in nature. Art helps us feel the current of grace. The binding love that draws everything together in an eternal outpouring.

© 2022 Arthur Aghajanian

Arthur Aghajanian

Arthur Aghajanian is a Christian contemplative, essayist, and educator. His work explores visual culture through a spiritual lens. His essays have appeared in a variety of publications, including Ekstasis, Tiferet Journal, Saint Austin Review, The Curator, and many others. He holds an M.F.A. from Otis College of Art and Design. Visit him at www.imageandfaith.com